This is a guest post by former Duck of Minerva blogger Betcy Jose, Assistant Professor at University of Colorado-Denver and contributor to Al-Jazeera and Foreign Affairs.

As the number of posts here suggest, lots of us are watching the fast-moving and somewhat unexpected events in Ukraine with great concern and interest. Others have expertly discussed the reasons for Russian military intervention in Ukraine and how the international community might respond to it (here, here, here, and here). I’d like to contribute a different angle to this complex story by inquiring into Russian narratives for its military action in Ukraine.

When Vladimir Putin requested the Russian parliament’s approval for authorization to use the military in Ukraine, he claimed Russia needed to act because of “the threat to the lives of citizens of the Russian Federation, our compatriots, [and] the personnel of the military contingent… deployed in… Ukraine.” Putin also made this argument to President Obama during their March 1 phone conversation.

That Russia might be concerned about its security interests with the ouster of a supportive Ukrainian President Yanukovych isn’t difficult to grasp. Not only is Crimea important to Russia historically and for identity politics, but Russia’s only warm water naval base is in the Crimean city of Sevastopol. A pro-Europe government in Ukraine, turning away from Russia and controlling Crimea, can have negative impacts on these Russian interests. Concerns for these interests provide strong motivations for Russian intervention. Which is why the use of humanitarian arguments to also justify this intervention are puzzling. In addition to protecting its soldiers, Russia asked its Parliament to authorize military action in Ukraine to protect its citizens. However, at the time of the request, there were few stories in the Western media about attacks against ethnic Russians or Russian citizens in Crimea prior to the intervention. So why bother?

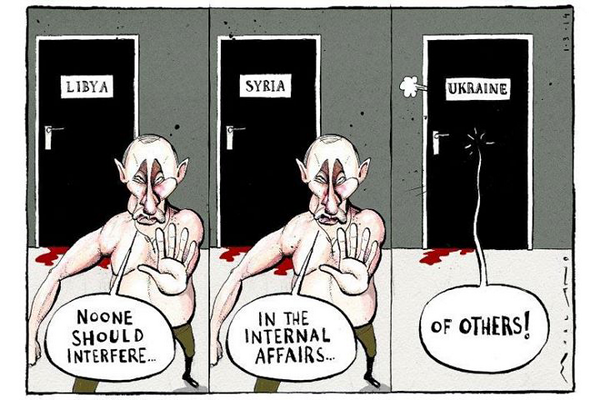

One obvious answer might be that the resort to humanitarian claims might provide legal cover for interest-driven intervention which violates international law. However, that argument is unsatisfactory for a number of reasons. First, the humanitarian argument is harder for Russia to make in this instance than in the case of its intervention in South Ossetia in 2008. As Stefes and George argue, Russian citizens had been attacked in South Ossetia prior to Russian military action there. Yet, as noted above, threats to Russians in Crimea had not yet materialized to the extent necessary to justify a rapid and internationally unsanctioned military intervention on their behalf. Second, the emerging norm of Responsibility to Protect (R2P) requires military force for humanitarian considerations to be used as a last resort. It would be difficult to argue that Russia exhausted diplomatic options prior to its use of force in Crimea. Third, international endorsement for the use of humanitarian force is preferable both for normative and interest based reasons. Prior to its conflict with Georgia, Russia arguably made its case to the UN Security Council about the need to protect Russians in South Ossetia to gain this approval. The desire to defray the costs of military action in Iraq is a reason some claim the United States pitched humanitarian concerns to the UN Security Council. However, as stated previously, Russia has not pitched its justification for intervention to an international audience but to a domestic and regional audience. Fourth, citing humanitarian concerns in Crimea opens Russia up to claims of hypocrisy for its obstruction of interventions in Syria and Libya, as the following cartoon depicts.

Thus, based on conventional interpretations of permissible humanitarian military action, Russia’s actions in Ukraine might not pass muster or seem consistent.

So why make the argument? One reason may be that Russia utilized these arguments to present an alternative justification for humanitarian action. In other words, Russia may be attempting to influence the still yet-to-be defined parameters of the emerging norm of R2P. As Chris Borgen argues about Russian rhetoric surrounding the Georgian conflict:

In the case of South Ossetia, Russia found a set of legal concepts different in application from how most states would have interpreted international law, resonated with the views of a regional audience that Russia was targeting. Thus, the primary way that Russia may be changing international law is not, at first, by convincing states of a different interpretation, but rather by providing voice to an interpretation that resonates with norms already accepted by a certain grouping of states. What Russia has really done is organize and rationalize a legal argument around existing norms that have been against the prevalent rules of international law and, possibly, started its own interpretive community that will legitimize its actions and, in certain aspects, allow it greater leeway.

Russian vetoes to intervention in Syria demonstrate a resistance to a version of R2P endorsed by the United States and its allies and strong support for the more established norm of nonintervention. However, it is clearly does not find the norm of nonintervention absolute, as illustrated by the Georgian and Ukrainian cases. The humanitarian arguments Russia put forth for intervention in Ukraine may be targeted to domestic and regional audiences that also resist more dominant ideas of humanitarian intervention. Russian ideas on humanitarian intervention may be more limited, based on the anticipatory humanitarian interests of a state’s own citizens, occurring in the intervener’s backyard, and where sovereign rights are somewhat ambiguous. In this way, rather than suppressing the norm of humanitarian intervention, Russia may be trying to shape it to reflect its normative preferences. In its effort to reposition itself in the global arena, Russia may be drawing not just on its material capacities but also on its abilities to shape the global normative structure.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

“So why make the argument?”

Why did Germany pretend that France had invaded its territory in 1914, thus necessitating a German declaration of war? (To say nothing of 1939.) Both instances seem pretty obvious, to this untutored reader anyway.

Betcy, I’m not sure I see this as a puzzle. The Athenians, Napoleon, Nicolas I, Hitler and others used similar normative appeals prior to military action. It’s pretty standard instrumentalism — in an attempt to diffuse domestic and international costs. I don’t see any evidence here that Putin is trying to influence the norm of humanitarian intervention or R2P with this rhetoric.

I agree that this is definitely instrumentalism at work – humanitarianism as cover. But he is using a very specific argument here, very similar to the arguments used during the Georgian war even though the facts don’t match and those arguments weren’t widely accepted in 2008. And I haven’t seen anything suggesting there is a wide necessity for these justifications for Putin’s domestic audience. Instead, I think you’re both right in a way- he’s throwing these claims out there to influence the undecided international audience (the rest rather than the West) and playing on some of the fears associated with the humanitarian intervention aspects of R2P to do so- in effect, he’s trying to undermine it by expanding its apparent scope. But as Bedescu and Weiss noted, it certainly didn’t work before…

Jon and Phil, thanks so much for your comments. Jon, I do agree with you that there is a very strong element of instrumentalism at play in Russia’s motivations for going into Ukraine. I am curious, though, about the justifications it used for what appears to be a strongly interest-driven act. To me, it seems that utilitarian-based justifications would have sufficed for garnering domestic support for the invasion when Russia made the humanitarian appeal. And it seems unlikely that a Western audience was going to accept the humanitarian argument and provide support for this move. This is why the humanitarian argument is puzzling to me. Could there be some other reason for making the humanitarian argument apart from attempting to diffuse costs (like shifting the idea of R2P)? And Phil, as you noted, just as these efforts were unsuccessful in the past, I don’t expect Russia’s efforts to have wide appeal this time around either.

It seems to me that the “Russian narrative” here is not a particularly Russian one but rather a “narrative” that more powerful countries tell when they invade less powerful/powerless countries, no? There are interesting parallels, in a variety of ways, with when the US invaded Grenada to “rescue” US medical students, not least declining powers in some trouble looking for ways to reassert themselves.

Or am I thinking about this the wrong way?