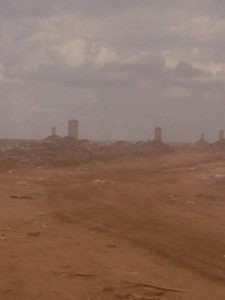

Two weeks ago as part of our class, we visited Brasilia’s landfill site, known as Lixão, which again underscored some of the incredible contradictions in the country. It is a vast site, with six open dumping sites, this is one of the largest landfills in all of Latin America. Controversy surrounds this landfill, as it is slated to be closed and moved some 45km away. The government is shutting down landfills like this one in favor of lined landfills with water protection systems. They have already closed Rio’s massive dump in 2012. Brasilia’s landfill harkens back to an earlier age, when unlined landfills with no specially designed containment ponds existed. However, this landfill won’t shut quietly.

It was already set to close some time ago, but the waste pickers don’t want this landfill closed right away because they live nearby.

Brasilia’s aircraft shape

The landfill is some 20 km from of the city and was created shortly after Brasilia was dubbed Brazil’s new capital in 1960. A planned city arrayed in the shape of an ultramodern aircraft, Brasilia was designed with the concrete architecture of the era, carefully laid out by planners to accommodate a small population of government bureaucrats.

While neatly lead out into government, diplomatic, commercial, and other areas, it is less clear the city, as relatively clean and functional as Brazil cities go, could accommodate a larger population and all the service workers required to keep that city clean and livable with its design aesthetic intact. Satellite cities have since sprung up some distance from Brasilia. They look quite imposing themselves with their skyscrapers.

The landfill sits at the edge of Brasilia’s National Park, a paean to the rapidly declining Cerrado landscape, the scrub tree savannas of the area that has increasingly given way to urbanization, cattle, and soy.

There is tremendous value in Brasilia’s garbage. Plastics, cardboard, food waste are all recycled by the 2500-3000 waste pickers, represented by seven different cooperatives, the community of recyclers who work on site and go through the day’s garbage from the 600 trucks that come here every day bearing garbage from Brasila’s supermarkets, offices and residents. About everything goes here, save tires which are sent elsewhere for recovery.

To the pickers, the plastics go for 20 reais a bag, a bit more than $10. A bag is a huge hulking sack, like five big garbage bags. About four of those are pressed into cubes and bundled to be sent to recyclers in São Paulo. 4 guys press about 50 cubes a day here, each cube fetching about 120 reais, a bit more than $60. The waste pickers walk around site with big bags for plastic, smaller bags for PVC and metals like copper and aluminum. For their own consumption, they also go through the garbage of supermarkets, as they are in this video.

It is unsafe work. We saw a guy who got hit by a truck taken away by ambulance. With a vast army of pickers on site with trucks dumping and bulldozing, this apparently happens about five times a week. Of course, there are kids on site, though they aren’t supposed to be there. There are 108 security guards and 28 municipal employees here, but the law forbids them from forcibly removing kids, many of whom accompany their parents as the money is better with some extra help.

It is unsafe work. We saw a guy who got hit by a truck taken away by ambulance. With a vast army of pickers on site with trucks dumping and bulldozing, this apparently happens about five times a week. Of course, there are kids on site, though they aren’t supposed to be there. There are 108 security guards and 28 municipal employees here, but the law forbids them from forcibly removing kids, many of whom accompany their parents as the money is better with some extra help.

The methane isn’t captured for energy or to reduce greenhouse gases, instead it is vented through the hundreds of short concrete tubes stuck into trash which extends down 50 meters below ground and 30 meters above. You can see the methane vapors coming off of the tubes, some of them alight and belching smoke.

Despite these issues, the landfill remains open. Through their mobilization, the waste pickers have convinced local authorities to delay the inevitable (the landfill was supposed to close last July and indeed the BBC reported plans to close the dump in 2002). Though the new site is set to have pre-sorting faculties for waste and will provide jobs for some number of people, it is far away. The waste pickers have built their ramshackle homes just nearby the existing dump in a town called Estrutural. They don’t want to move, and their are a modicum of government services, schools, hospitals, and playing fields that serve them. Who knows what a move would bring?

Like these authors we read for our class, I’m sympathetic to the situation of the waste pickers and recognize that they are performing an important function. Still, it’s hard to see how much longer this 50 year unlined landfill can stay open. It has three unprotected containment ponds that have to be continually pumped to prevent drainage into the nearby national park. There are no doubt other hazards associated with the risk of fire, explosion, as well as to the waste pickers themselves.

So, I’m not sure what the right ask is here, faster closure of the landfill?, more support to move and resettle the waste pickers? Whatever the answer, I’m struck by incongruity of Brasilia’s relative wealth an cleanliness, the 1 billion reais (more than half a billion US dollars) the Brazilian government put in to build a World Cup stadium in a city that lacks first division football (and with cost overruns, the stadium costs ran upwards on $900 million by some reports, some $600 million over the initial budget).

Again, that contrasts leaves me feeling ambivalent about this World Cup, as a soccer enthusiast but, more importantly, someone who cares about struggling communities around the world. Whether through my purchase of tickets for the games or our consumption of soy beans or beef, we are implicated in the lives of poor people in Brazil and the rainforests, two issues of significant importance both locally and globally.

We were fortunate to tour the Brasilia landfill with the support of Fabiano Toni, a professor at the University of Brasilia who helped set up the visit with local staff but also translated and provided essential background on the landfill.

The travails of waste pickers in Brazil were documented in 2010 in an award winning documentary called Waste Land, available on Hulu below.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments