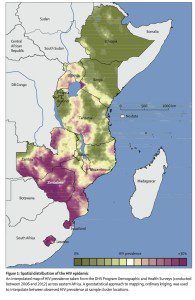

Earlier this spring, I had a chance to talk to Mark Dybul, the head of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria and former administrator of PEPFAR, the U.S. bilateral AIDS program. At the time, he expressed optimism about using geo-referenced data on HIV/AIDS prevalence to better to target AIDS foreign assistance. In advance of the recent AIDS conference in Australia, researchers (which include Dybul) released a new study in The Lancet ($) that modeled that potential in Kenya by focusing on the hot spots of high HIV/AIDS prevalence (see above East Africa map, purple represent high prevalence levels). Dybul’s comments were music to my ears. For the past year, I’ve been part of the AidData Research Consortium’s project (ARC) to develop sub-national foreign assistance data. Already that project has worked to help geo-reference World Bank, African Development Bank and Asian Development Bank projects as well as foreign assistance from all donors in a number of countries. As many of you know, I’ve been part of climate vulnerability mapping for the better part of five years through my work on Africa through the Minerva Initiative and the CCAPS program at the Strauss Center. This fall we will embark on a new Minerva project to look at disaster vulnerability and complex emergencies in South and Southeast Asia. In this post, let me say a few more words on the importance of data granularity and aid targeting. The logic behind data granularity is fairly simple. If you know where the problems are concentrated geographically, you can target aid accordingly, which may be particularly important in an era of tight aid budgets. The Economist ran a story on the importance of data granularity and these findings:

One watchword here is granularity. The world’s AIDS maps, which once recorded rates only on a country-by-country basis, now do so region by region. This means effort can be focused on the worst-affected places within a country, not just on the worst-affected countries. Deborah Birx, America’s global AIDS co-ordinator, thinks such focus is essential. It will, she believes, keep downward pressure on the infection rate without too much extra expense. A study published in the Lancet on July 19th, to coincide with the conference, supports her in this. Sarah-Jane Anderson of Imperial College London and her colleagues have crunched the numbers for Kenya and concluded that focusing on the worst-affected parts of that country could, over 15 years, reduce the number of new infections by 100,000 at no extra cost.

You see HIV/AIDS is not distributed evenly over the country. The Lancet author conclude that future infections are likely to come from a handful of areas:

Across the 47 counties in Kenya, estimated HIV prevalence varies substantially, from less than 1% to 22% in the year 2013. In the model, the estimated number of new infections is concentrated in five counties (Migori, Homa Bay, Kisii, Nairobi, and Kericho) that account for almost 40% of all new HIV infections in the country

While political criteria may ultimately prove more important in the allocation of aid and spending both within and between countries, granular georeferenced aid on baseline problems like HIV and where aid money actually gets spent at least provide some intellectual ballast as to where resources ought to be directed. This is a little easier if aid allocation is based on a single indicator such as HIV/AIDS prevalence. As we have discovered in our work on Africa, this is harder if you are trying to develop a multi-dimensional index of underlying need such as vulnerability, where modeling choices can greatly influence outcomes and different modeling groups may generate very different portraits of underlying vulnerability. In the HIV/AIDS context, the Global Fund is championing this approach and, as the main multilateral donor, it can largely authoritatively decide which maps of need are appropriate. Sarah-Jane Anderson and her co-authors in The Lancet piece write of the approach and significance:

A uniform strategy, which does not use available intelligence on the epidemic, will fail to be as effective as a strategy that does. By use of a public health approach that focuses resources based on an epidemiological understanding of subnational geographical areas and key affected populations, and selects the package of interventions most likely to have an effect according to the drivers of each HIV stronghold, the efficiency and effectiveness of programming could be greatly increased.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

A few things: 1) your text suggests that the map is of Kenya. But it’s not. 2) a lot of these mapping exercise reveal that HIV prevalence is highest at border crossings, mines, and areas with a lot of sex workers and drug users. No real shock there – we’ve known that for 30 years. Increasing funding to these sites is only going to be effective if it all comes with the political will to address these populations with effective programs and policy changes such as decriminalizing MSM, SW and drug use. But it frequently doesn’t. So I’m less optimistic about how great this is. For the police it can be handy though to have a granular map of where to bust these folks.

John, yes, the Lancet article is mostly about Kenya but the map itself is of the wider region. You are right. They do more pullout maps in the main text of the hot spots around Nairobi. I think the maps reveal that at least in Kenya that the hot spots are not country-wide, that the high prevalence levels are concentrated in and around Nairobi, for the most part. Zambia and Zimbabwe still look like a more generalized epidemic. I guess the question on policy instruments is does having more fine-grained geographic data give the Global Fund more political cover to do fund focused interventions on those populations that you described. Since they still need partner governments on the ground, you raise an important question.

Governments distribute resources on purpose. That includes health care resources. Lets assume (reasonably) the ruling group wants to maintain their political office. The ruling group doesn’t rely on everyone to maintain political office, only a part of the population. Lets call them the selectorate. I would anticipate much lower HIV rates among the selectorate than everyone else.

Maybe you can distribute health resources through a partner government to peoples for whom the ruling party is indifferent. Certainly, they will block attempts to distribute resources to peoples supporting their political competitors. The question, as I see it, is how do you incentivize the group in control of the government not to try to corruptly suck up these resources and distribute them to their own cronies?

Also, I see both green and purple borders on the map above suggesting borders alone are not a good alternative explanation.

By the way, I expect ruling parties in countries outside of Africa, include yours and mine, to behave this way too.

I didn’t really follow your comment on green and purple but that might be a function of losing the legend. I realize that WordPress cut off the rest of the graphic. See the complete image I inserted into the main text. It’s a little small but you can click on the image for a clearer view.

I take your point about applying selectorate theory, but that can only go so far. Urban areas might be in the constituency of the ruling party and still be have high prevalence despite overtures by the government to address the problem among their people. Or, you could have a situation as you had in South Africa where the Mbeki failed to address HIV even among his supporters because he denied that HIV caused AIDS.

I think the Global Fund can encourage the ruling party not to use these resources in a corrupt fashion by cutting the money off if services are not delivered. They can also work through and empower NGOs to keep the country honest. The Global Fund faced a crisis of accountability a couple of years ago when a small portion of its multi-billion portfolio was misappropriated. That was a cautionary moment, and the controls are likely even tighter now.

Selectorate theory can be an attractive explanation that may explain central tendencies of many ruling parties, but it’s like using structural realism as a theory of foreign policy, other factors matter too and may shape outcomes in decisive ways.

Thanks for the thoughtful reply.

To clarify the border comment, all I meant is that your map doesn’t seem to show consistently high levels of HIV in border areas, contrary to the previous mapping exercises John cited in the comments.

Thabo Mbeki’s beliefs were certainly an odd (and granular!) factor in the South Africa case. As a practical matter, I imagine some level of misappropriation probably has to be tolerated to produce HIV reduction. Cutting funds for failed services delivery will obviously not lead to HIV reduction. Dealing with governments trying to game these funds is at the least going to take a really good sales pitch to convince them it’s in their interest.

You quoted Migori, Homa Bay, Kisii, Nairobi, and Kericho as being particularly troublesome. If this need isn’t a result of a purposeful lack of resource allocation by the government, I agree, the puzzle becomes really granular. What are the microincentives producing this macrooutcome? To say it another way, why are individuals so risk accepting with this disease? Do they believe it won’t reduce their lifespan or well-being beyond what they would otherwise expect?

This is great post by the way. I wish I was meaningfully involved in a project with such potential to help so many people. Please keep us posted.