Today is World Wildlife Day, and species we think of as part of the fundamental awesome creatures of the natural world – elephants, rhinos, and sharks – face unprecedented risks of extinction, particularly as a result of rising demand from Asia and China in particular. I’m currently teaching a year-long class on Global Wildlife Conservation for which my students have been writing some excellent posts on the poaching crisis and what can be done. If you are not familiar with this problem, this brief post provides a bit of background.

Over the past couple of years, news of the global poaching crisis of iconic species like elephants and rhinos has spread. Elephant tusks are prized for ivory for carvings and trinkets, with increased purchasing power and greater China-Africa commerce and ties leading to surges in demand. Countries in Central Africa have experienced steep declines in elephant populations due to poaching, losing by one estimate 64% of their elephants in the past decade. Late last year, this culminated in news of involvement by China’s presidential delegation in ivory smuggling in diplomatic bags out of Tanzania in 2013. This week, China announced a one-year ban on imported ivory, which is welcome news, but this is a critical time for the global community to put pressure on the Chinese government to rein in domestic demand forever. Even as China announced this positive move, elsewhere aging Zimbabwe dictator Robert Mugabe celebrated his 94th birthday by treating his guests to baby elephant.

The situation for rhinos is also acute, with poaching having increased in recent years because of demand for rhino horn and its purported utility as a cancer-fighting agent (Rhino horn is made of keratin, the same stuff as our finger nails so is useless as a medicine). Vietnam is seen as the epicenter for increased demand, as false rumors spread of its medicinal properties in recent years. Demand was so severe that the price spiked in $100,000 per kilo in 2013, prompting thieves to raid European museums for specimens. While rhino horns grow back, their value is prompting poachers to kill animals and hack the remaining bits of their skulls to get at the last little bit.

Africa, particularly South Africa, is home to the largest population of rhinos remaining in the world, unevenly split between the white rhino and the far more endangered black rhino . Asian rhinos have dwindled to near extinction with some subspecies already having disappeared.

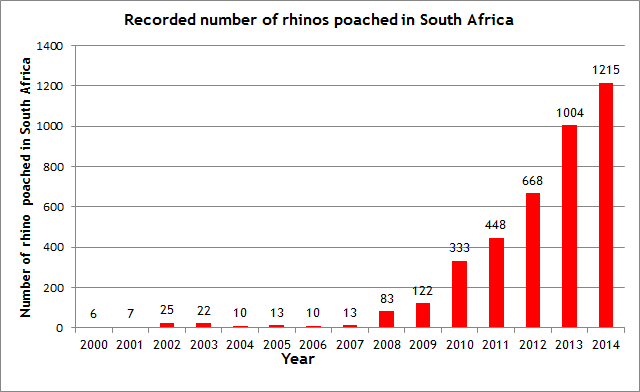

South Africa has the largest population of rhinos in Kruger National Park, but even South Africa, with more capacity than many countries in Africa, has been hit by a massive spate of rhino killings, up from negligible numbers in 2009 to more than 1200 in 2014.

What is To Be Done?

My class is grappling with these questions in a series of six papers, examining public-private partnerships, multilateral governance, security, ecotourism, sport hunting, and demand reduction. Both range state capacity building and recipient country demand reduction are critical. While interdiction in range states, particularly in Africa, is important, success will not be achieved unless Asian countries, particularly China, reduce their demand. While some have advocated legalization of the sales to create private sector incentives for management of these species, such efforts, including a 2008 sale of ivory to China, backfired and stoked demand rather than killed the market.

So, how do demand reduction work? Here, we don’t yet have much good information. Despite the Obama Administration’s presidential directive and task force acknowledging the importance of evidence-based work on demand reduction, there is not yet a strong consensus of what works. My class is going to employ some experiments in I hope China and Vietnam to see what persuasive messages work. There is some evidence that the Chinese public is persuadable.

The NGO WildAid ran some campaigns to dissuade the Chinese to stop consuming shark fin soup, a delicacy that was increasingly being served at weddings and banquests and devastating world shark populations. With ads featuring former NBA basketball player Yao Ming and actor Jackie Chan among others, that campaign claims a spectacular success of reducing demand by 50-70% in a few short years. Similar campaigns are underway by WildAid for rhinos and elephants, again engaging Yao Ming. Whether the campaign or a Chinese government ban on shark fin at banquets or both drove that decline is unclear.

WildAid is doing one thing right by looking for locally appropriate messengers, but I think we still have some ways to go to fine-tune our understanding of why the Chinese public is responding to these messages (fear of consequences of being caught vs. improved understanding of the damage to nature) for shark fin and whether similar messages for other products/species will be as effective.

Here, I encourage those of you interested in conservation and persuasive messages to employ your analytical talents to this cause. We’re grappling with these questions on our class blog, but this is an all hands on deck moment for global wildlife.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

“aging Zimbabwe dictator Robert Mugabe celebrated his 94th birthday by treating his guests to baby elephant.” Wow, seriously Mugabe? Baby elephant?