As a new Duck, who (like Cai & Tom) took a while to consider what to blog about, I finally decided – long-winded academic that I am – to write a series of posts on the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag campaign. To this end, I draw on materials for a keynote I just delivered at the University of Surrey’s Center for International Intervention‘s conference on “Narratives of Intervention: Perspectives from North and South” (#cii2015). Here I go:

On April 14, 2014, 276 girls between the ages of 15-18 years were abducted from a school in Chibok, Northern Nigeria, days before they were set to take their final exams. A group named Jama’atu ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad, better known as Boko Haram, claimed responsibility for the abduction. The girls’ kidnapping, despite its spectacular scale, initially received sparse attention in the media. However, after local activists took to twitter with the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls on April 23, within a matter of days (by May 1, 2014), the hashtag was trending globally and the mainstream media began to cover the event putting increased pressure on the Nigerian (but also the U.S.) government to ‘do something.’

The impulse to demand that ‘something’ be done is of interest in the context of campaigns of global feminist solidarity in particular, because presumably well-meaning efforts often have adverse effects. The attention provided by global campaigns, such as the hashtag campaign for #BringBackOurGirls, brings greater awareness to the plight of women and girls around the world, but at what cost? Is awareness, even if it is based on simplistic narratives and promotes ‘solutions’ disconnected from the reality on the ground, helpful? Does it matter when celebrities hold a #BringBackOurGirls sign – or do we need a more critical stance, as Ilan Kapoor has argued? What does it mean for the first lady of the U.S. to remark on the abduction during her 2014 Mother’s Day address and to call for action?

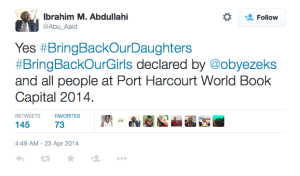

What is striking in the age of social media is the accelerated pace with which an issue achieves global reach. The hashtag #BringBackOurGirls was first used by Ibrahim M. Abdullahi (@Abu_Aaid on twitter) on April 23, 2014, when he commented on remarks by Oby Ezekwili (@obyezeks on twitter) at the Port Harcourt World Book Capital 2014 event:

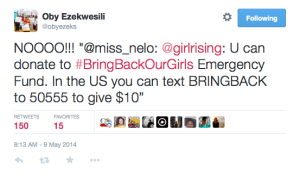

Ezekwili, a former World Bank Africa executive and Minister of Education, who has become a leading figure in the movement since, later tweeted her many followers with the following message:

Ezekwili, a former World Bank Africa executive and Minister of Education, who has become a leading figure in the movement since, later tweeted her many followers with the following message:

While hashtag started in Nigeria, it quickly spread to the Nigerian Diaspora in the UK and US – and beyond, as this time-lapse shows [<- watch it!!!].

While hashtag started in Nigeria, it quickly spread to the Nigerian Diaspora in the UK and US – and beyond, as this time-lapse shows [<- watch it!!!].

As a hashtag travels and gains global prominence, it becomes more disconnected from the context within which it emerged and the knowledge of actors who initially started the campaign. The distance, along with the simplicity of the messaging that can be captured in 140 characters, exacerbates problems (feminist) social movements have always struggled with. These include, but are not limited to, (1) agreeing on what is to be done; (2) making sure that all efforts are geared toward that main objective; and (3) careful and critical examination of the likely effects of any demands, especially in terms of feminist ideals. As campaigns capture the imagination of many, affiliated actors add their own interpretation and agenda items, a process that is facilitated by the nature of hashtag activism where anyone can join. This highlights the need to be particularly attentive to the question of whether the (feminist) goals of particular campaigns are being appropriated and compromised in the process.

The case of #BringBackOurGirls is no exception, as the following example shows: CNN’s coverage initially attributed the hashtag to Ramaa Mosley, a filmmaker from California involved with the Girl Rising documentary and campaign. After social media pointed out the error, CNN quickly retracted this account. Capitalizing on all the attention, meanwhile, on May 9, 2014, Girls Rising featured a call for donations on twitter and their website. Again, social media was quick to respond:

Consequently, Nigerian activists felt the need to make a statement noting that their campaign was not and would not be seeking donations.

Consequently, Nigerian activists felt the need to make a statement noting that their campaign was not and would not be seeking donations.

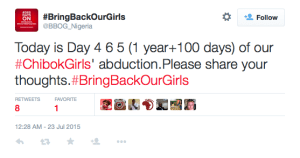

It is unclear how involved Mosley, who runs the U.S.-based #BringBackOurGirls website as well as a facebook page, was in this snafu – but the incident certainly highlights the ease with which hashtag campaigns can get appropriated. Meanwhile, to mark the passing of one-year since the abduction of the #ChibokGirls (a hashtag that has become widely used by the Nigerian campaigners), U.S.-based activists organized a #GlobalSchoolGirlMarch in which #ChibokGirlsAmbassadors in Nigeria participated – it seems therefore that earlier disagreements have been forgiven. While it might still appear to some that Western-led interventions are making a crucial difference in the campaign, for the most part activities have been lead by activists in Nigeria. They have been demonstrating at the Unity Fountain in Abuja for over a year, have set up a comprehensive website and campaign to pressure Nigerian leaders, and continue to send out daily tweets which count the days the girls have been missing. Today, incidentally, marks one year and 100 days since their abduction:

Notwithstanding derailments such as the one briefly discussed here, social media campaigns often have a powerful impact and have transformed the way governments respond to protests, notes Zeynep Tufekci. Indeed, Nigerian #BringBackOurGirls campaigners got involved in recent presidential elections and met with newly inaugurated President Buhari earlier this month. Subsequently, on July 21, 2015, Buhari announced his plan to fight Boko Haram and get the girls back. As things develop on the ground, it is particularly important to assess the impact of the #BringBackOurGirls campaign more broadly, including the call by those far away from Nigeria itself that ‘something’ be done as these demands are shaped by multiple frames of reference. What these frames might be will be the topic of Part Two of this series – stay tuned! Meanwhile, please share your thoughts below.

Notwithstanding derailments such as the one briefly discussed here, social media campaigns often have a powerful impact and have transformed the way governments respond to protests, notes Zeynep Tufekci. Indeed, Nigerian #BringBackOurGirls campaigners got involved in recent presidential elections and met with newly inaugurated President Buhari earlier this month. Subsequently, on July 21, 2015, Buhari announced his plan to fight Boko Haram and get the girls back. As things develop on the ground, it is particularly important to assess the impact of the #BringBackOurGirls campaign more broadly, including the call by those far away from Nigeria itself that ‘something’ be done as these demands are shaped by multiple frames of reference. What these frames might be will be the topic of Part Two of this series – stay tuned! Meanwhile, please share your thoughts below.

Annick T.R. Wibben is an Associate Professor at the University of San Francisco. Her research straddles critical & feminist security studies, international theory, and (feminist) international relations. She also has a keen interest in methodology, representation, and narrative.

Interesting post. My two cents? It’s pretty hard to demonstrate causality, but I’m persuaded that the local Bring Back Our Girls movement played a key role in turning popular sentiment against President Goodluck in parts of Nigerian unaffected by the Boko Haram insurgency. Prior to the protests–and particularly, prior to the Goodluck admin’s ridiculously inept response–the survey data from NOI and elsewhere suggests that very few Nigerians outside the north saw the state response (and the violence that accompanied it) as problematic. But several months of senior PDP officials publicly suggesting that the protesters were out to personally discredit the president in order to replace him with a northerner in 2015, along with the embarrassing international tv interviews of Ngozi, the Minister of Information, and others, really does seem to have led to greater public frustration in the administration’s performance.

Brandon – sorry to only reply now. I think what you’re saying is correct… though I only have anecdotal data. And it’s certainly been interesting to see the interactions with President Buhari after the elections…