My first post on the Duck focused on the emergence of the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag and campaign, pointing also to the ease with which hashtags can get appropriated and campaigns derailed. Yesterday, #BringBackOurGirls Nigeria (@BBOG_Nigeria on twitter) started a one week campaign to mark 500 days since the abduction.

My first post on the Duck focused on the emergence of the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag and campaign, pointing also to the ease with which hashtags can get appropriated and campaigns derailed. Yesterday, #BringBackOurGirls Nigeria (@BBOG_Nigeria on twitter) started a one week campaign to mark 500 days since the abduction.

Given the continuation of the campaign, in today’s post I want to dig a bit deeper in examining the urge to do “something”: Why do some events capture our attention while others fail to produce any kind of reaction? What kind of reactions are helpful? And – for whom?

The initial (and ongoing) framing of events plays a crucial role in this process – in this case, a humanitarian emergency frame which overlaps in insidious ways with the global “war on terror” narrative (see Wibben 2011). What is more, both of these also need to be examined for their continuation of imperialist tendencies and deployment of colonial tropes, and those are also deeply gendered and raced.

Let’s begin with a quick look at the #Kony2012 campaign (and if you haven’t heard about it – go check it out on the Invisible Children site or just watch the video). In their analysis of the #Kony2012 campaign, Sullivan, Landau & Kay found that it “achieved initial popularity owing to its depiction of a clear enemy figure who elicited moral outrage,” but that attention to the issue faded when the complexities of the situation were tackled in a subsequent video (#Kony2012 Part II: Beyond Famous).

The #BringBackOurGirls campaign, especially in its global iteration, similarly featured a clear enemy figure: Boko Haram – and more specifically Abubakar Shekau [1]. We see this in media depictions, such as CNN’s Shekau profile, which describes him as follows:

“He is the face of terror. A ruthless leader with a twisted ideology. And the sadistic architect of a campaign of mayhem and misery.

And yet, very little is known about Abubakar Shekau, the leader of Boko Haram.

He operates in the shadows, leaving his underlings to orchestrate his repulsive mandates. He resurfaces every once in a while in videotaped messages to mock the impotence of the Nigerian military. And he uses his faith to recruit the impressionable and the disenfranchised to his cause.”

This description neatly fits into the familiar, simplistic Islamic terrorist narrative that characterizes the U.S.-lead “war on terror” (see also Wibben, forthcoming). This familiarity, coupled withe the humanitarian appeal, facilitates moral outrage and triggers the demand to do “something.”

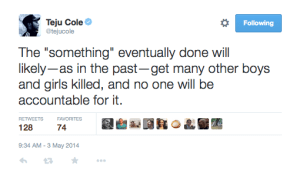

More insidiously, a framing where the West saves brown women from brown men (Spivak 1988) fits squarely into the imperialist narrative of “saving natives.” This narrative has long been criticized by postcolonial feminists, but is alive and well in what Teju Cole described as the White-Savior-Industrial-Complex in his analysis of the #Kony2012 campaign and subsequent commentary on #BringBackOurGirls in May 2014. Himself from Nigeria, Cole (@tejucole on twitter) was quick to note the hypocrisy of the way the #BringBackOurGirls campaign was picked up in the Western media in a series of tweets (<-read them, they’re worth it!). Doing “something” is infinitely more complex than imagined by those who urged others to sign petitions – and might be counterproductive:

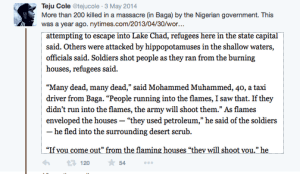

Indeed, the Nigerian government had been doing “something” for quite a while – their hardline military approach had at times lead to the mass murder of civilians, Cole pointed out:

Indeed, the Nigerian government had been doing “something” for quite a while – their hardline military approach had at times lead to the mass murder of civilians, Cole pointed out:

For the past several years, and specifically since the declaration of a state of emergency in the three Northeastern districts of Yobe, Borno and Adamawa in 2013, the Nigerian government has not made any serious efforts to engage Boko Haram other than militarily. As a recent Human Rights Watch report notes, Shekau made several statements indicating that his intent was “to retaliate against the government for its alleged arrest and detention in early 2011 and 2012 of family members of Boko Haram members, including the wives of Shekau.” On this reading, the abduction of the girls is a (justifiable?!) reaction by Boko Haram to the Nigerian government’s hardline approach. The availability of this framing indicates, however, that a more careful assessment of the realities on the ground is crucial to any effort to do “something” and – ultimately, to the success of the #BringBackOurGirls campaign.

Indeed, were one to consider possible grievances that underlie the longer history of Jama’atu ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad, particularly under its summarily executed former leader Mohammed Yusuf, one might detect an anti-colonial impulse. The group’s rejection of Western influence in Nigeria, where much of the elite is foreign-educated and the North of the country is in worse shape now than it was under British colonial rule, at least in the early 2000s found considerable support among the broader population. When Boko Haram is translated as simply “Western education is forbidden” (rather than the more accurate translation “Western influence is forbidden”), this situational context goes unnoticed. This framing doesn’t examine the West’s complicity and aligns neatly with a storyline of Islamists denying girls an education, another familiar trope in the global “war on terror” narrative (see also the attention given to Malala Yousafzai’s appeal for the Nigerian girls).

Without attention to the specifics and variations of the longer colonial context, and past as well as current interests of regional and global actors, the abduction of hundreds of girls in Chibok becomes a singular event. If we really want to do “something” we might do better to consider it as one spectacular instance in a series of horrific violence against girls and boys, women and men by a variety of actors (local, national & global) trying to assert control from colonial times to today. Doing “something,” then, clearly is not as straightforward as imagined.

Meanwhile, in the last 500 days, lots has been done. The next post in this series will consider the effects of all these little (and big) “somethings” and in particular demands for and actual military action against Boko Haram … stay tuned!

[1] According to the Chadian president Idriss Déby, Shekau has now been ousted as leader of Boko Haram and has been replaced by Mahamat Daoud who supposedly is interested in negotiation with the Nigerian government. But – this claim, and the Chadian involvement more generally, is a story for another day…

Annick T.R. Wibben is an Associate Professor at the University of San Francisco. Her research straddles critical & feminist security studies, international theory, and (feminist) international relations. She also has a keen interest in methodology, representation, and narrative.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks