The following is a guest post by Rachel Merriman-Goldring, Susan Nelson, Hannah S. Petrie at William and Mary’s Institute for the Theory & Practice of International Relations.

For decades, survey research has suggested that women lack confidence in their answers, responding ‘don’t know’ or ‘maybe’ at significantly higher rates than their male counterparts. Initially, this trend on political surveys was attributed to topic-specific political knowledge gaps between men and women.

However, recent research, including a study on the confidence gap between male and female economists, suggests that, while background knowledge matters, other structural factors, including gender-differentiated socialization, may contribute to women’s tendency to select ‘don’t know.’

Our work on the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) Project at the College of William & Mary provides us with access to a unique database of survey responses from International Relations (IR) scholars, most of whom hold Ph.D.s in political science.

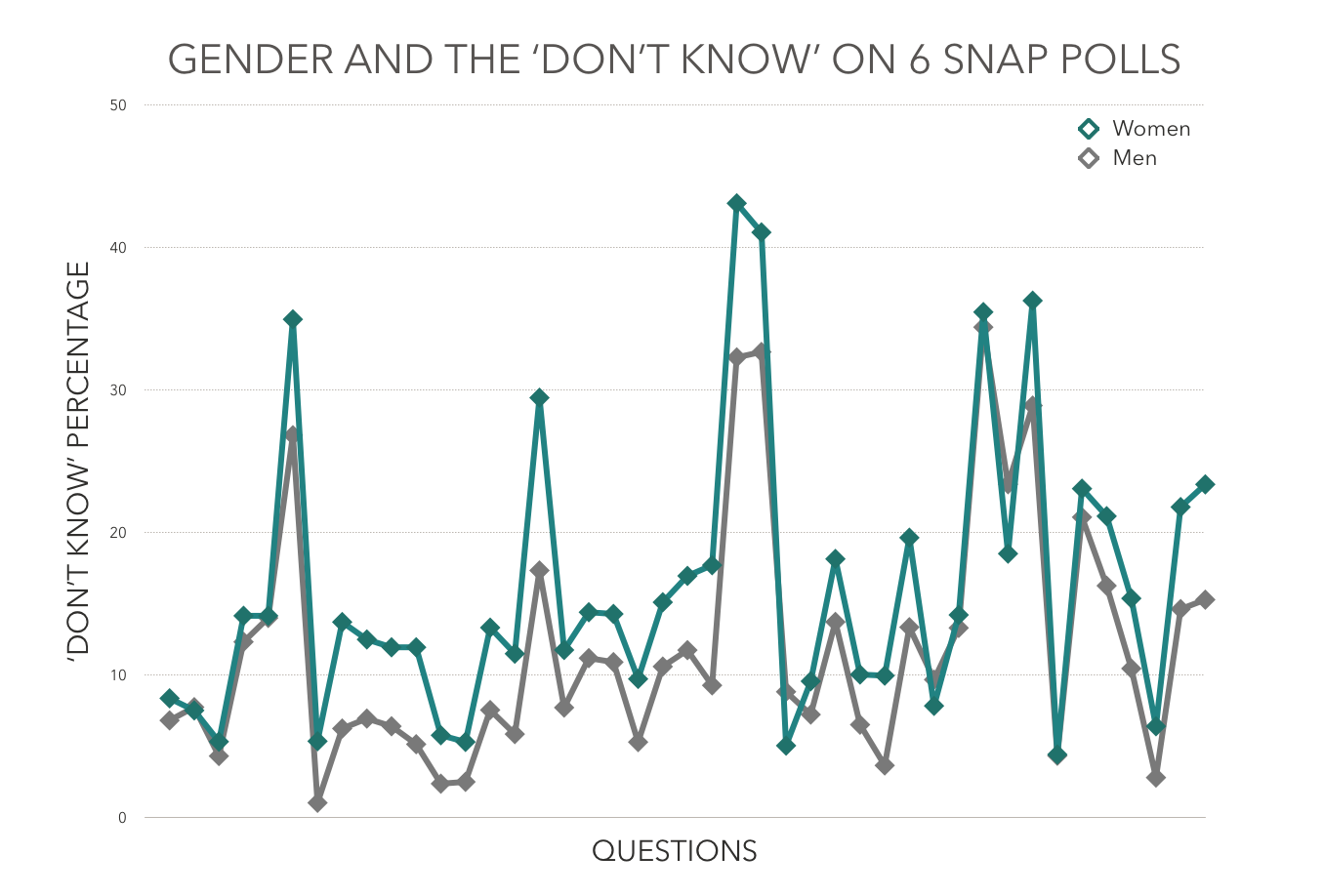

Over the past 14 months TRIP has conducted 6 snap polls consisting of 43 questions with ‘don’t know’ as on option. Women responded ‘don’t know’ more than their male counterparts on 39 of the 43 questions. Figure 1 provides a visual of this gap.

Figure 1 shows the responses of U.S. International Relations scholars from all 6 TRIP snap polls. Women consistently selected ‘don’t know’ at a significantly higher rate.

TRIP also recently collaborated with the Wisconsin International Policy and Public Opinion (WIPPO) Project to ask 1158 Americans questions that were also asked on TRIP’s Snap Polls, allowing us to compare public and scholarly responses.

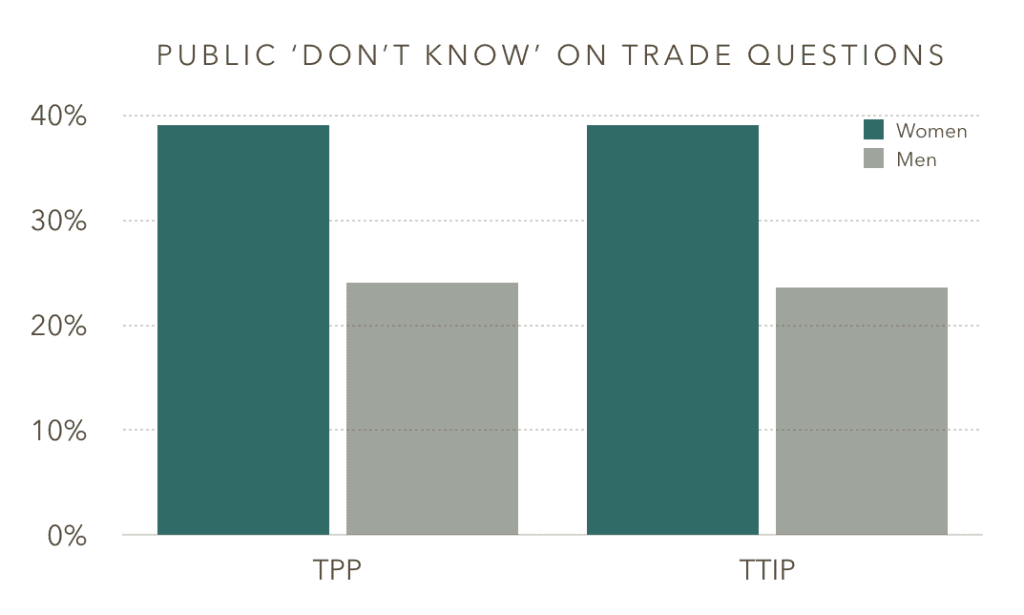

Questions on free trade agreements were especially revealing. When members of the U.S. public were asked about contemporary issues in IR, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed free trade agreement among Pacific Rim countries, and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), a proposed free trade agreement between the United States and the European Union, women were more likely to select ‘don’t know.’ In response to questions about the effect of the TPP and TTIP on their financial situation, for instance, more than 39% of women in the general public chose the ‘don’t know’ option, compared to only 24% of men. Figure 2 shows the responses to both questions.

Figure 2 plots the responses of members of the U.S. public from WIPPO’s Snap Poll. There is a statistically significant gap between male and female responses on questions about the two free trade agreements.

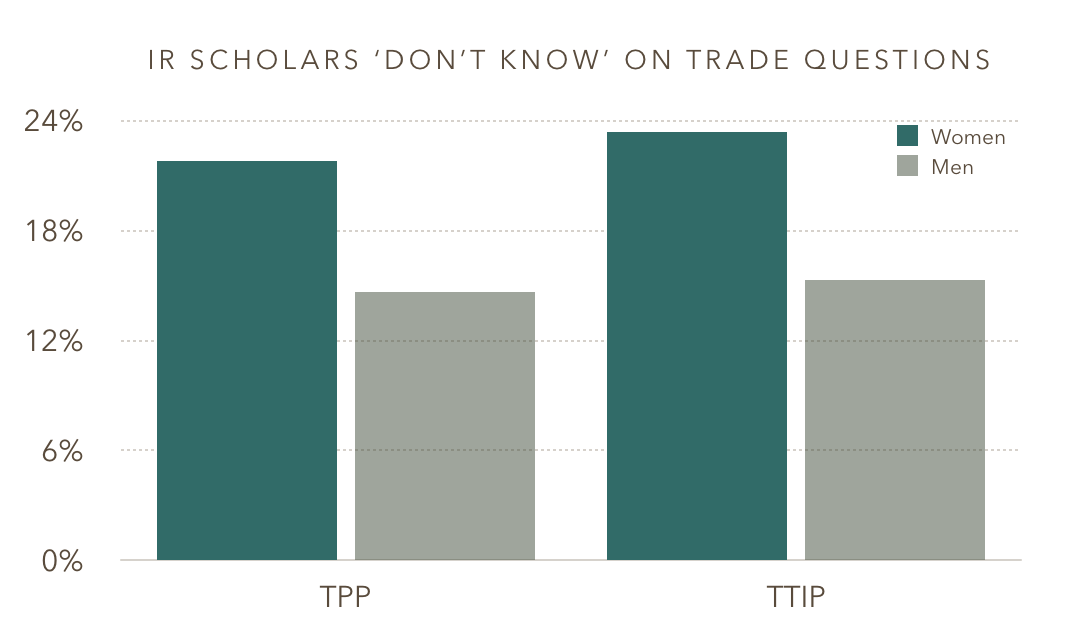

The confidence gap between men and women was only slightly narrower among IR scholars, even if the overall percentage of ‘don’t know’ responses was lower among these experts. More than 22% of women said they didn’t know how the TTP and TTIP would affect their financial situation, while 15% of male scholars selected that response option. The gap in these responses is highlighted in Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows the responses of U.S. International Relations scholars from TRIP’s Snap Polls. When asked the same questions as the public, female IR experts were also significantly more likely to select ‘don’t know.’

The persistence of the gap suggests that, despite significant steps towards gender inclusivity in the academy and beyond, structural factors like socialization continue to affect the ways women perceive and express their knowledge. This research contributes to a larger conversation on gender-based behavioral differences, including women’s tendency to apologize more frequently and female students’ propensity to speak up less frequently in the classroom.

This work shows that political knowledge is not a sufficient explanation for women’s tendency to select ‘don’t know’ more frequently. We explore potential explanatory factors, including differences among scholars (age, topical expertise, status within the discipline, etc.) and differences among questions (predictive, normative, descriptive, etc.) in our larger project on gender and confidence.

Amanda Murdie is Professor & Dean Rusk Scholar of International Relations in the Department of International Affairs in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Help or Harm: The Human Security Effects of International NGOs (Stanford, 2014). Her main research interests include non-state actors, and human rights and human security.

When not blogging, Amanda enjoys hanging out with her two pre-teen daughters (as long as she can keep them away from their cell phones) and her fabulous significant other.

Is there a reason that this project is framed in terms of why women lack confidence? Is it not just as probable that men are too confident in their level of expertise? An alternative question might be: “why are men more likely to think they know everything?”

It seems to me that overconfidence among male IR scholars is at least as problematic as female lack of confidence, especially in the academic endeavor. Yet most studies of this sort (like those regarding apologizing and not speaking up that the authors mention) are framed as women failing to measure up against a “normalized” male standard. Perhaps practices that are gendered feminine, like admitting to not knowing something, also have something positive to add to IR.

Totally agree Kirstin; you beat me too it! Why do women lack confidence or why do men lack humility? It would be interesting to follow up the poll with a pop quiz on the TTIP. Then you could measure the bullshit gap (or perhaps the “Propensity to bullshit” – often a much more accurate description of those opinionated men in class).

I mean, does anyone really know how TTIP will directly affect their individual financial situation? That is surely pretty speculative at best. Rather than capturing gender confidence or lack of in terms of gender, I would say the take away point from that is why such a a large % IR scholars are so insecure that felt they should answer they DO know. I mean it reminds me of how people assume that geographers should know every capital city, volcano and type of cloud in the world. Apparently though, IR scholars lack the confidence to just say, “no that is not my area of expertise”. Why is that?

Absolutely agree. I don’t think this data necessarily shows women “lack confidence” at all; rather perhaps they are confident when they actually have a basis for being sure about something and humble about what they don’t know! To be honest enough to admit you don’t know something conveys confidence, in my opinion!

Read this on my feedly and came over to make this comment, but see others have beaten me to it. Concur.

Kristin, thank you for your comments!

You’re absolutely right that a confidence gap (as shown by our data), shouldn’t necessarily be taken to mean that women are underconfident, and could just as easily imply that men are overconfident. This article is the first step in a larger project (that will have way more than 600 words to grapple with such a complex issue!). Thanks for your useful insights!

Rachel

I agree that there may be a gendered component to overconfidence here. But there may also be a generational effect. Women have only come into IR in non-negligible numbers in the past generation. Current training places far more emphasis on evidence from data analysis, which often results in ambiguous results, whereas previous training (not just in IR) placed far more emphasis on detailed knowledge and intellectual authority. These days, not knowing the answer is acceptable — perhaps even encouraged — but a generation ago, it would get you fired. If you selected male scholars of the same age and training as the female scholars, you might find less of a difference.

This is a particularly important point as the response of institutions to gender inequalities in pay, status etc is too often to offer ‘confidence building’ seminars for individual women. While the research on women answering ‘don’t know’ more often than men is enlightening, framing the data as connected to a lack of confidence inadvertently plays into the hands of those who see inequality in our profession and others as principally caused by women’s behaviour rather than by institutional policies, structural discrimination and unconscious bias.

in other words, we tell the truth more often than men! Maybe more particularly in anonymous (?) surveys.