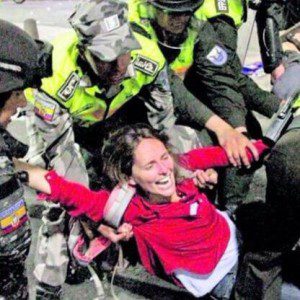

Over the weekend news came from Ecuador that Dr Manuela Picq of Universidad San Francisco de Quito, had been beaten and arrested while participating in a legal protest over indigenous rights as a journalist. Initially hospitalised as a result of injuries sustained at the hands of police, she was informed that her visa had been cancelled due to her having engaged in “political activity” and that she would be deported from Ecuador, where she has lived and worked for the past eight years. She is currently being held in a hotel that is used to detain illegal immigrants until her case is heard this afternoon.

[UPDATE: Manuela has been released after the judge ruled that her arrest was not justified and detention unreasonable.]

Once news had broken, the reaction has been swift and condemnatory from activists and academics alike. A petition on Change.org calling for Manuela’s deportation to be halted has gathered more than 6,000 signatures at the time of writing, letters of support are being sent to President Correa and his government, and a protest has been held in Ecuador.

Academia and activism has long had a fraught relationship. Many take the position that the two are incompatible, while others argue that activism is a moral imperative. This is not a new debate, and I’ve no intention of rehashing it here given the wealth of discussion that already exists on the matter, including contributions by academics such as Professor James Arvanitakis, Professor Kevin Gannon, Dr Eric Grollman, Dr Kelly J. Baker and Elisa Arond amongst others.

Yet for students and scholars of International Relations, is there any real way to avoid (as opposed to ignore, which can certainly be done) the fact that not only do we study international politics, but we also enact them, both in our everyday lives and our academic choices? If we accept the impossibility of neatly divorcing the personal and the political, I’d argue that, like it or not, we’re all activists, if only by our choice to be inactivists.

I’ll try to explain a little more fully, before coming back to Manuela’s current situation and why this all matters.

For the last few years I’ve taught a introductory international politics course. It’s a whistle-stop one-trimester tour of issues in IR: sovereignty and statehood, nationalism and self-determination, international law and the UN, globalisation, global political economy, American power and the international order, war and security, human rights and intervention, poverty and inequality.

The aim of the course is to begin to develop knowledge of these issues and related debates. It’s also the starting point for socializing students into the discipline of International Relations, adding the question of “how to?” to those of “what’s what?” and “who’s who?” How do we study IR and what are the implications of taking up particular theories, methods and perspectives?

Asking the “how” question leads to two further questions for students to consider: What sort of world do you want to live in? At what and whose cost? These questions are often met with a frown of disapproval or confusion. Questions hang in the air: What’s this got to do with the study of IR? What’s the “right” answer?

But my aim is not to suggest that there is a “right” answer to these questions. Rather, it is to make students to think about the political implications of how they engage with and understand IR. The theoretical and conceptual positions we adopt are not just an intellectual exercise, but have tangible and wide-ranging implications for people’s lives, including our own.

In this respect, we are all living IR everyday, and our own and others’ experiences have the potential to reveal how the world and its workings as powerfully as any concept or theory. Even if at first glance it might seem more explicitly political than the situations that many of us encounter, Manuela’s current predicament is actually illustrative of the fact that we are all subject to the consequences of state and international politics in our lives in multiple ways. Professor Javier Corrales explained¹:

Why the Manuela Picq case is important. It’s not just about academic freedom, which it is. It’s not just about the right to protest peacefully, which it is. It’s not just about state targeting (of women, partners), which it is. It’s not just about the state acting arbitrarily to cancel a person’s legality or about about state intolerance. It’s about both. But it’s also about the rights of foreigners to do academic work as expatriates. Passport blindness is fundamental to the social sciences. We cannot have good research, good universities, or even good democracies if we don’t invite the insights that come with internationalization. It’s a form of diversity that is indispensable to knowledge and accountability. Stop Manuela Picq’s deportation. Sign the petition if you haven’t yet.

I’m not going to end with an exhortation to sign the petition – that’s your choice to make. But whatever decision you make, make no mistake that IR is as much about the political as politics, and that as subjects – as well as scholars – of IR the political and the personal are inextricably linked for all of us.

¹ Originally posted on Facebook, subsequently provided by email with permission to quote.

Cai Wilkinson is Senior Lecturer at Deakin University in Melbourne Australia. Cai’s research focuses on societal security in the post-Soviet space, with a particular focus on LGBTQ rights in Kyrgyzstan and Russia.

0 Comments