It was with a distinct sinking feeling yesterday that I learnt that conference rooms for the EISA’s upcoming 9th Pan-European Conference on International Relations have been renamed after eminent theorists of European origin and that there is not a single woman amongst those selected to be honored.

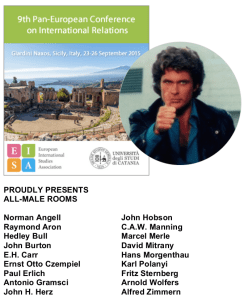

A close reading of the conference program brought together the following list of names, which was posted on the Congrats, you have an all-male panel Tumblr:

To add insult to injury, some conference rooms have retained their usual Italian names, so it’s not even as though there wasn’t space to include some female theorists, even if one wished to stick solely to Europeans on the grounds that it’s a European association and conference (and I’d note that this reasoning is far from unproblematic both in terms of defining “Europe” and deliberately excluding “non-European” theorists from a discipline that purports to be “international”).

Coming after controversies about diversity at ISA annual conventions in 2014 (underrepresentation of women on ISA committees) and 2015 (underrepresentation almost complete absence of non-white scholars in the Sapphire Series), and Saara Särmä’s All-Male Panels blog attracting widespread media attention from outlets including the BBC, Time, and CBC earlier this year, this really can only be described as one those excruciatingly exasperating facepalm moments that with a little thought could have been avoided. After all, declarations about the importance of recognising diversity and addressing the underrepresentation of minorities are pretty much de rigeur in the discipline, as well as in academia and indeed organisational culture in general. So, surely by now asking oneself whether what one is about to do is going to perpetuate existing inequalities and stereotypes (in this case that the leading lights of European theorising are all male and deceased) should be if not second nature, then certainly part of one’s decision-making process?!

Assuming agreement with this point (not guaranteed, I know), then the next question that occurs is how exactly do organisations keep managing to get it so wrong? It might be tempting to view this sort of instance as evidence of active efforts to maintain the current status quo, but I’m more a fan of the principle that things are far more likely to occur as a result of cock-up rather than conspiracy.

In this particular case, I cannot reasonably countenance that the exclusion of women from the list of names is deliberate. I’d also venture that many of those involved in the organisation of the conference are feeling pretty dismayed about the outcry over the list of scholars and what has been inadvertently – almost certainly erroneously implied – as a result. The call for section chairs includes reference to gendered violence as part of the conference theme; the list of sections is distinctly “critical” and post-modern-friendly with a number directly speaking to issues of diversity (S10 Decolonizing International Relations; S15 Feminist Global Political Economy; S33 Non-Europeans’ Europe; S47 Re-thinking, Re-writing, Re-imagining Sexual Violence); the conference organising committee is 50/50 male/female; and EISA’s governing board and council is currently comprised of 5 women and 7 men (for comparison, the ISA’s current ExComm includes 2 women and 10 men). In other words, there’s a good deal of evidence that suggests there’s a commitment to diversity that goes beyond lip-service.

Yet despite all of this, the naming of conference rooms after exclusively male scholars still happened and people are understandably exasperated and angry. In this respect I think there are two points that bear further consideration:

Firstly, greater diversity in organisational structures does not necessarily result in a different politics. Addressing entrenched inequalities of representation requires active organisation-wide commitment. This is not easy given the scale and complexity of organisations, but commitment to diversity must to be practice-based rather than declarative, and institutional rather than individual. Otherwise it’s all too easy for this comittment to be undermined and rendered meaningless.

Secondly, diversity does not just exist along a single axis. Adding female scholars of European origin to the list of names would address one shortcoming, but it would not address the continued marginalisation of non-Western scholars in the discipline. In this respect, the key point is that getting it right along one axis of diversity, be it gender or theoretical pluralism, does not absolve one of responsibility to be as inclusive as possible along other axes as well. To paraphrase Flavia Dzodan, commitment to diversity will be intersectional or it will be bullshit. This is especially important due to how dynamics of marginalisation along one axis frequently coincide with and are exacerbated by those along another axis/other axes, as non-male feminist IR scholars or non-Western non-positivist IR scholars (to name but two examples) know only too well.

Within IR as a discipline, we exist and operate within multiple, intersecting and often conflicting hierarchies of knowledge and power. As a rule, this means that there are no solutions that will satisfy everyone and that effecting positive change at the systemic or even just organisational level is often a slow and frustrating process. Nevertheless, we have a responsibility to speak out when we see missed opportunities to challenge shortcomings in existing practices and approaches as a commitment to making positive change happen. To reinterate the All-Male Panels blog’s message to our professional associations: “You can do better, and we expect more”.

Cai Wilkinson is Senior Lecturer at Deakin University in Melbourne Australia. Cai’s research focuses on societal security in the post-Soviet space, with a particular focus on LGBTQ rights in Kyrgyzstan and Russia.

I am just curious who would be on your list for inclusion. I am trying to think of any non-American female IR scholars that have had an impact on the field that is even close to those the scholars the rooms were named for. The dead issues is reasonable though, imagine the politics of choosing among living scholars…”Why did Keohane get a room but not Mearsheimer or Wendt or Finnemore (did you see that, I added a female scholar!)”

Hannah Arendt? Seems like she had some things to say about power and violence both domestic and international.

Nothing but respect for Arendt…a stellar figure. Just not an IR scholar, but I would probably give her a room anyway