In early September, the circulation of the now iconic picture of Alan Kurdi, the little Syrian Kurdish boy who drowned along with his mother and brother in the attempt to cross the Aegean Sea, prompted me to write a post reflecting on what ‘we’ as academics might do. I argued that we could, possibly, use “our knowledge of global affairs to connect the dots and lay bare how Alan’s story” is emblematic of so many themes we touch upon in our research – and indeed, the moment created by the (ethically difficult) circulation of the picture became an opening to provide depth and nuance for those willing to listen.

I suggested that, if academics wanted to do ‘something’ in response, this something might include telling “the stories of all the children who died crossing the Mediterranean – and their parents and grandparents, and aunts, and uncles.” Now, it would be presumptuous to think that Anne Barnard of the New York Times read my post (and she is not an academic either), but imagine my delight to see her piece on the Kurdi family’s journeys published yesterday.

I suggested that, if academics wanted to do ‘something’ in response, this something might include telling “the stories of all the children who died crossing the Mediterranean – and their parents and grandparents, and aunts, and uncles.” Now, it would be presumptuous to think that Anne Barnard of the New York Times read my post (and she is not an academic either), but imagine my delight to see her piece on the Kurdi family’s journeys published yesterday.

Written with the help of contributing reporters Hwaida Saad, Karam Shoumali, Amro Refai, Tim Arango, Ben Hubbard, and Kamil Kakol (in Turkey, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Germany), the New York Times front page piece traces not only the journey of Alan’s nuclear family, but the extended Kurdi clan. As good journalistic storytelling, it highlights the journeys of some family members whose experiences mirror the displacement and death faced by the extended family, which in turn is exemplary of that of the population of Syria (and other peoples displaced by current and ongoing wars in the Middle East and elsewhere). Unlike the kind of storytelling I would hope would be the ‘something’ an academic could add, however, Barnard’s piece only hints at the complicated web of global politics that colors the Kurdi families’ journeys. She writes:

These short paragraphs contain in them broader stories: What might an academic storyteller add about the relevance of ethnicity/ nationality (often not chosen as much as imposed and/ or made relevant by circumstances beyond the control of those caught up in its throes)? Or, about the origins, development, and possible futures of the conflict in Syria and beyond? What could we add about the other children, women and men who have drowned in the Mediterranean this year and in the past – and global (& EU) policies that are likely to continue to produce this kind suffering? For example, Barnard touches on the issue that Turkey does not extend refugee status to Syrian refugees (see also Can Mutlu’s piece on this), making it that much harder for the Kurdis and others to move on, but she fails to note how a recent EU deal with Turkey effectively condones this practice… so, again, an academic might add the technical knowledge about shifting EU refugee policies (and an unwillingness of member states to welcome migrants) to complicate the story.

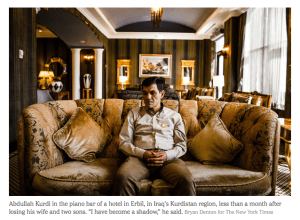

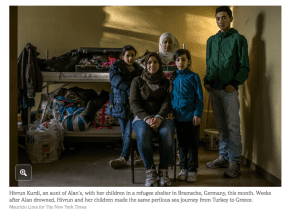

Alan’s death, which became known to us because someone took a picture that touched many (also because it was circulated widely), and his family’s story, brought to our attention again by Barnard’s article, has helped humanize an often unfathomable and overwhelming crisis in the Middle East and Europe for many. This is no solace to Abdullah Kurdi, whose grief is palpable in his description of himself as a shadow and whose journey since early September has lead him to repeatedly note that he’d rather have died with his family – but there is also hope in the journey of Abdullah’s brother Mohammed, who is resettling in Canada with the help of their sister Tima (Alan’s aunt), and his sister Hivrun who finally made it to Germany with her children (on the same perilous route) where she reunited with her husband.

Alan’s death, which became known to us because someone took a picture that touched many (also because it was circulated widely), and his family’s story, brought to our attention again by Barnard’s article, has helped humanize an often unfathomable and overwhelming crisis in the Middle East and Europe for many. This is no solace to Abdullah Kurdi, whose grief is palpable in his description of himself as a shadow and whose journey since early September has lead him to repeatedly note that he’d rather have died with his family – but there is also hope in the journey of Abdullah’s brother Mohammed, who is resettling in Canada with the help of their sister Tima (Alan’s aunt), and his sister Hivrun who finally made it to Germany with her children (on the same perilous route) where she reunited with her husband.

Their stories matter, just like the many others who are waiting to be told. They make it harder for us to look away and ignore how (often our own governments’) policies precipitate hardship for others. As I argue in Feminist Security Studies: A Narrative Approach (Wibben 2011), these personal narratives are also security narratives – worthy of being taken just as seriously by scholars as abstract discussions of great power strategy, arms sales, or Turkish and U.S. foreign policy interests in Syria and beyond. When we take these (personal) security narratives seriously, it becomes clear that “there is always more than one story to be told and that the ‘normality’ presented in narrative is always contextual. Narratives shift and slide” (Wibben 2011: 109).

Examining the conditions of possibility for some stories to be told and circulated (and to capture our attention as Alan’s story has) is one way to take these narratives seriously – posts by Megan MacKenzie, Tiina Vaittinen, Swati Parashar, and most recently Federica Caso, all speak to this in some or another manner. While Swati and Megan worry about the dangers of adding to the circulation of some stories and reinforcing particular framings, urging more reflection and even silence, Tiina and Federica point out to that academics have a political and ethical responsibility to speak out in the face of injustice. Federica suggests that speaking also implies listening: to those we write about, to each other as scholars, and to our inner voice, as Swati urges. There is no neutral position to which one might retreat: “Politics and international politics is a dirty business… and whether we get involved through political activity or scholarly research, there is no way that we can avoid the problem of dirty hands,” writes Federica.

I would like to add just a few short considerations to this conversation. For one, the stories (and images) we scholars engage (or not) are already circulating and they are intelligible through frames that are familiar to us. These frames are shaped by the contexts we find ourselves in: Hearing, seeing, listening, contemplating, and speaking all happen within a particular (temporal, spatial, personal, professional, cultural, linguistic, etc.) context. This context, or horizon (in hermeneutic terms), shapes how we understand a particular situation – how we make it meaningful to us (and, later, to others). It is important to appreciate that these horizons constantly shift as new experiences, encounters, conversations, contemplative silences, and images expand our horizons (see also Wibben 2011). What is more, we are able to deliberately seek out new experiences and attend, as much feminist scholarship continues to do, to the stories of those on the margins.

Second, the contexts for understanding and meaning-making also have an important element of temporality to them. As Cynthia Enloe has urged repeatedly, a key facet of good (feminist) scholarship is to stay attentive over the long haul – when the cameras have moved on to the next story; when Abdullah Kurdi has buried his children, when his story gets questioned (and he’s accused of being a smuggler – though he wasn’t), and when he is whisked away to meetings with the rich and powerful who did not attend to his family when they were alive. As Barnard’s piece begins to outline, the circulation of Alan’s image, his aunt’s activism, and the reactions of those who (for the first time or not) saw the humanity of the refugee/ migrant attempting impossible journeys through this story, did provoke (or at least hasten) some changes. This, of course, is not the end of the story – nor is there a single story to be told here. However – unlike the media which moves from one story to the next in its frenzy to fill the 24/7/365 media cycle, academics have the luxury to be slower thinkers and writers.

Those of us in (ever dwindling) privileged academic positions (possibly even enjoying tenure) are able to stay attentive over the long haul, develop deep knowledge about a region or policy issue, and delve into contexts and connections. With that, in my view, comes a responsibility to do so to the best of our ability – and to do so critically and reflexively. As I previously wrote, “how open a researcher is to engaging in (self-)reflexive research processes interrogating their own positionality and privilege, questioning its impact on what can be perceived, being willing to be surprised, and adopting a stance of curiosity – all of these matter greatly” (Wibben 2011: 110) as we tell others’ stories. Reflexivity, as the scholars featured in Researching War: Feminist Methods, Ethics & Politics (Wibben 2016) also point out, needs to start early and can be an antidote to the same old style that pervades much academic (IR) scholarship.

This style, which requires that academics speak with an authoritative voice, one that conveys certainty in the face of a complex and uncertain world (and which is warranted when those in power refuse to admit certain truths), is at a disadvantage when covering the nuances of, at times seemingly inconsistent, (personal) experiences. In such a framework of certainty it does not “make sense” that Alan’s aunt Hivrun, after several previous failed attempts to cross the Aegean Sea in a dinghy and near death experiences after which she refused to try again despite her family’s pleas, would make the same perilous journey across just weeks after her nephews died there (see Barnard’s piece). Or maybe it makes perfect sense if we were to pay more attention to the challenges that mark the family’s everyday experience in Turkey?

This style, which requires that academics speak with an authoritative voice, one that conveys certainty in the face of a complex and uncertain world (and which is warranted when those in power refuse to admit certain truths), is at a disadvantage when covering the nuances of, at times seemingly inconsistent, (personal) experiences. In such a framework of certainty it does not “make sense” that Alan’s aunt Hivrun, after several previous failed attempts to cross the Aegean Sea in a dinghy and near death experiences after which she refused to try again despite her family’s pleas, would make the same perilous journey across just weeks after her nephews died there (see Barnard’s piece). Or maybe it makes perfect sense if we were to pay more attention to the challenges that mark the family’s everyday experience in Turkey?

Paying attention to the personal stories, in all their complexity and with varied inconsistencies (which narratives can accommodate, see Wibben 2011), teaches us much about global politics and engaging them also makes our work more relevant to broader audiences. Additionally, thinking and writing our scholarship as stories – to be questioned, expanded, made more nuanced – provides room for a variety of others to insert skepticism, share their truths … and to continue the conversation.

Annick T.R. Wibben is an Associate Professor at the University of San Francisco. Her research straddles critical & feminist security studies, international theory, and (feminist) international relations. She also has a keen interest in methodology, representation, and narrative.

0 Comments