With each passing week, Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee, makes statements that challenge the basic operating assumptions of U.S. foreign policy, whether it be through his nonchalance about a trade war with China, repudiation of alliance commitments to NATO and Japan, or honoring the countries’ debts. The question that emerges from this: does the American electorate care?

While presidential candidates have to pass some semblance of a commander in chief test of credibility with the electorate, the conventional wisdom is that foreign policy rarely matters much in U.S. presidential elections, outside of moments of crisis. See my blog post here, as well as posts by Dan Drezner and Elizabeth Saunders.

A recent example comes from the recent kerfuffle over Ben Rhodes’ New York Times interview. Drezner argues efforts on both sides of the Iran Deal debate last year failed to move the public, mostly because the issue did not resonate with the American people.

This, however, is an unusual year, where we have a Republican candidate in Donald Trump with no government experience who will likely face a Democratic nominee in Hillary Clinton, a former first lady, Senator, and Secretary of State. One or more San Bernadino, Brussels, or Paris-type attacks might make foreign policy more important. Do we have any evidence though to assess this claim or concern?

Recently, Bethany Albertson, Shana Gadarian, and I explored some of these issues on The Monkey Cage using pilot data from the 2016 American National Election Studies (ANES) survey nationally representative sample of 1200 Americans. The pilot was internet-based and fielded in January of this year with data collected by YouGov.

Our piece, written in the wake of the Brussels attacks, examined whether and how anxiety about terrorism might affect political attitudes and vote choices this fall. We found that those who were more anxious about terrorism evaluated Trump more favorably, though other polls suggest that people might rally around the candidate with more experience.

That said, we didn’t analyze the question of the relative salience of foreign policy compared to domestic issues. ANES data also allows us to explore issue salience and whether people care about foreign policy in the first place. Here is what I found.

Measuring Salience

Salience is the relative importance people attach to different issues. Though few people are single-issue voters, some issues are likely more important than others in figuring in to people’s vote choices. Where foreign policy sits in the mix of issues is debatable.

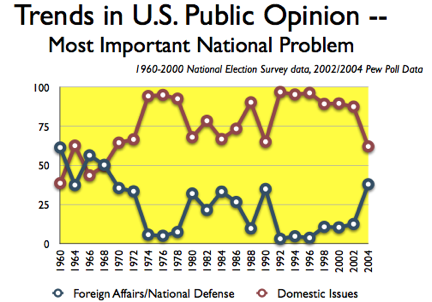

In the past, the ANES survey asked people to identify the most important problem in an open-ended fashion. Jon Monten and I mined this data for our 2012 PSQ article to conclude that foreign policy, since Vietnam, has generally not been all that salient to the American public, though had increasingly become more important in the wake of 9/11 and the Iraq war.

Scholars such as my UT Government Department colleague Chris Wlezien have argued that the “most important problem” question is problematic because it conflates what people consider to be “important” with what they consider to be a “problem.”

Consider, for example, the economy. We have reason to believe that the economy is always an important issue to voters, but that it is a problem only when unemployment and/or inflation are high, for example.

David RePass, for his part, has written about problems in wording that made it impossible to use the answers from the 2004 ANES survey. He also wrote about the limited number of response options and the placement of this question near the end of the survey after respondents had been primed about many issues.

A 2015 proposal on issue salience to ANES for this cycle noted the “sparseness” of data on issue salience. In some years, ANES survey respondents were asked about their attitudes to a fixed-list of issues. In 2012, it was limited to gun control and religion. The proposal went on to note problems of the way fixed-list questions were asked in the past:

In other years, such as 2008, the ANES has included more issue salience questions, but all are in a single format that asks: “How important is this issue to you personally?,” with five choices ranging between “not important at all” and “extremely important.” While certainly useful in providing a measure of issue salience, this question format has some problems. The first is a problem discussed by Jacoby (2006) in the context of core values: when respondents are allowed to provide separate ratings of the importance of a series of values or issues, there is a tendency to rate all items as highly important and ignore trade-offs that can arise between mutually desirable end-states…

The proposal goes on to note that items like “national security” have typically been missing from these lists. Furthermore, there is the problem of interpersonal comparability.

Worse still, this question format appears to encounter the problem of interpersonal incomparability (Brady, 1985). Simply put, some respondents seem more likely to report higher values on the salience scale across separate issues than others.

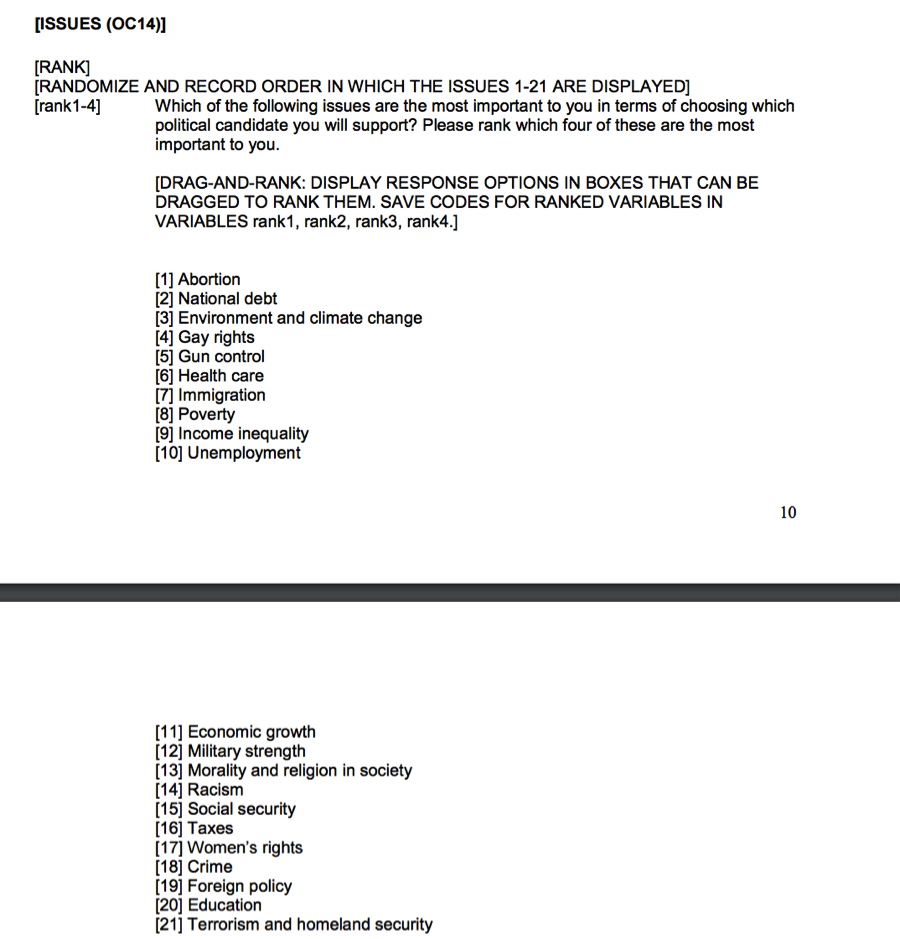

The proposal suggested including 14-16 items and asking respondents to rank their top four most important issues. The 2016 pilot survey provided a list of 21 issues, of which three are related to foreign policy — “military strength,” “foreign policy,” and “terrorism and homeland security.” Respondents were asked to identify their top four issues. Different from past years, this year’s pilot survey also asked people to evaluate these issues in terms of evaluation of the candidates: “Which of the following issues are the most important to you in terms of choosing which political candidate you will support?”

The Findings

So what did people say? Economic growth was ranked by the highest proportion of respondents — 12.72% — as their highest ranked issue. That was followed by terrorism and homeland security (12.33%). Only 2.08% ranked “foreign policy” as their highest issue while only 3.29% did the same for “military strength.” Together, the three foreign policy options amounted to about 18% of the first choice issues.

If you group domestic economic issues, the percent of 1st preferences adds up to a large fraction (about 50%). That list would include economic growth along with poverty (1.98%), income inequality (4.41%), health care (9.04%), social security (7.59%), unemployment (3.94%), taxes (4.26%), and the national debt (6.05%). Other issues like immigration (6.55%) and climate change/environment (4.38%) are both foreign and domestic issues in some ways.

Do these values for foreign policy problems constitute high or low salience? One might argue that because terrorism and homeland security commanded the second highest share of 1st preferences, this is evidence of high salience. However, because there are 18 different domestic issues to choose from, the domestic issue space is diluted and divided in to many related issues. It might be more telling to have a more balanced list of say five foreign policy issues and five domestic issues to see what people choose.

Another way to look at this is the cumulative percentages of top 1-2, top 1-2-3, and top 1-2-3-4 rankings. Terrorism and homeland security command 22.11%, 29.39%, and 35.46% of those cumulative priority rankings. That’s roughly comparable with economic growth on its own. Military strength’s cumulative 1-2-3-4 ranking is 16.85% while foreign policy is 14.43%. The other big single issues with high cumulative top four rankings include health care (35%), social security (29%), and the national debt (23%). Again, by aggregating across related economic issues, the domestic issues would far outstrip foreign policy.

Foreign policy might matter in a close election if the voters that care about foreign policy are located in swing states and themselves persuadable to vote for the party that seems stronger on national security. As I wrote on this blog, this has been a worry for national security Democrats worried about the Republicans’ traditional dominance on this issue and the deterioration of the Democrats’ high standing on foreign affairs in the wake of the Iraq war.

Republicans care about terrorism and homeland security in the ANES pilot survey. 24% of Republicans identified this as their top issue compared to only 6.5% of Democrats and slightly more than 10% of Independents (chi2 = 48.74, p=.00). The differences between Democrats and Independents are not statistically significant.

I also looked at gender, whether people voted in the 2012 elections (as a signal of whether or not they likely might actually turn out this time), race, and education. Neither gender nor education appeared significant. Having voting in the last election marginally seems to make one less inclined to identify terrorism and homeland security as a top 4 issue (chi2 = 16.52, p= 0.0078). Being white makes someone more inclined to identify terrorism as a top issue (chi2 = 10.06, p = 0.0117) while being black makes them less likely to (chi2 = 11.80, p = 0.0007. However, including Republican and white in the same model leaves white statistically insignificant (logit model, Republican p=0.000, white p=.105).

The last thing I looked at was age. If you are under 30 (which was about 20% of the sample), you are statistically less likely to identify terrorism and homeland security to be a top issue(chi2 = 8.16, p= 0.0236) or top 4 issue (chi2 = 10.37, p= 0.0255). People under 30 do care about other issues more than older people such as education and the environment, so it’s not as if younger voters are apathetic about all issues. However, given that older people are more reliable voters, this suggests that foreign policy might be a bit more salient to likely voters than the population as a whole.

The evidence here is mixed. While foreign policy pales in comparison to domestic policy, these concerns still resonate with a significant percentage of Americans, particularly if we expand our ambit to the top four issues. That said, this survey was conducted in January 2016. Salience can change with events, and we have many months for the electorate to see things differently leading up to election day.

* Thanks to Bethany Albertson and Shana Gadarian for substantive and technical advice on this blog post, though all the errors are mine!

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments