The publication of the long-awaited Chilcot Report on Britain’s role in the Iraq War last week produced a flurry of activity, with journalists desperately skimming through the 2.6m words within the three hours they were allocated prior to full publication. Perhaps not surprisingly, much of their attention was focused on whether or not Tony Blair could be held legally and morally culpable for the chaos that has ensued since the invasion back in 2003. And despite fears that it would be a whitewash, the report was pretty damning in its assessment of both the justifications for war and its execution. Amongst its key findings, the report found that Blair deliberately exaggerated the threat posed by Saddam Hussein, the case for war was presented with ‘a certainty which was not justified’, the intelligence was flawed and often went unchallenged, advice about the possibility of sectarian violence was ignored and post-war planning was described as being ‘wholly inadequate’. Crucially, the report also concludes that the ‘peaceful options for disarmament had not been exhausted’ and the war was ‘not a last resort’.

The publication of the long-awaited Chilcot Report on Britain’s role in the Iraq War last week produced a flurry of activity, with journalists desperately skimming through the 2.6m words within the three hours they were allocated prior to full publication. Perhaps not surprisingly, much of their attention was focused on whether or not Tony Blair could be held legally and morally culpable for the chaos that has ensued since the invasion back in 2003. And despite fears that it would be a whitewash, the report was pretty damning in its assessment of both the justifications for war and its execution. Amongst its key findings, the report found that Blair deliberately exaggerated the threat posed by Saddam Hussein, the case for war was presented with ‘a certainty which was not justified’, the intelligence was flawed and often went unchallenged, advice about the possibility of sectarian violence was ignored and post-war planning was described as being ‘wholly inadequate’. Crucially, the report also concludes that the ‘peaceful options for disarmament had not been exhausted’ and the war was ‘not a last resort’.

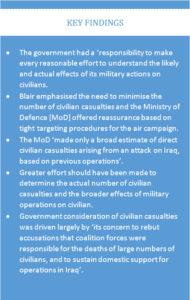

Reactions to the report have been pretty incredible, with The Guardian describing it as ‘an unprecedented, devastating indictment of how a prime minister was allowed to make decisions by discarding all pretence at cabinet government, subverting the intelligence agencies, and making exaggerated claims about threats to Britain’s national security’ and The New York Times arguing that the ‘inquiry’s verdict on the planning and conduct of British military involvement in Iraq was withering, rejecting Mr. Blair’s contention that the difficulties encountered after the invasion could not have been foreseen’. But what has been largely ignored in all the furore is the inquiry’s scathing critique of the government’s attitude towards civilian casualties. Given that the discussion on collateral damage is the last section of a twelve volume report, nestled between a chapter on the welfare of service personnel and an annex on the history of Iraq from 1583 to 1960, it is perhaps not surprisingly that there has been little discussion of its findings. But it is well-worth looking at its conclusion because they reveal a lot of about how civilian casualties were framed, why the government was so reluctant to count the dead and how it perceived the data collected by other organisations, such as the Iraq Body Count.

One of the reasons that the publication of the report is so interesting for us as academics is the fact that it is accompanied by a treasure trove of previously unseen memos, briefings and policies that provide an interesting insight into the debates that were happening (or not happening) behind closed doors. When it came to the issue of civilian casualties, the report reveals some clear tensions about whether or not the Ministry of Defence (MoD) could or should be collecting data on the death and injury caused to civilians. We discover that Blair requested a detailed assessment of likely collateral damage during a meeting on January 15, 2003. But when the MoD produced a casualty estimate report a few weeks later, it would only provide details of the expected losses amongst coalition troops. Although technically possible to provide a collateral damage estimate for individual operations, it stated that the list of targets was not sufficiently defined to ‘allow an estimate to be produced for the air campaign as a whole’ (pp177-178). All they were prepared to do was provide details of civilian deaths during similar operations in Iraq back in 1998 and 1999, which indicated that 150 civilians would be killed and another 500 injured. They also refused to provide an estimate for urban operations in Basra, preferring instead to use data collected from the region during World War Two (p178).

One of the reasons that the publication of the report is so interesting for us as academics is the fact that it is accompanied by a treasure trove of previously unseen memos, briefings and policies that provide an interesting insight into the debates that were happening (or not happening) behind closed doors. When it came to the issue of civilian casualties, the report reveals some clear tensions about whether or not the Ministry of Defence (MoD) could or should be collecting data on the death and injury caused to civilians. We discover that Blair requested a detailed assessment of likely collateral damage during a meeting on January 15, 2003. But when the MoD produced a casualty estimate report a few weeks later, it would only provide details of the expected losses amongst coalition troops. Although technically possible to provide a collateral damage estimate for individual operations, it stated that the list of targets was not sufficiently defined to ‘allow an estimate to be produced for the air campaign as a whole’ (pp177-178). All they were prepared to do was provide details of civilian deaths during similar operations in Iraq back in 1998 and 1999, which indicated that 150 civilians would be killed and another 500 injured. They also refused to provide an estimate for urban operations in Basra, preferring instead to use data collected from the region during World War Two (p178).

This reluctance to monitor civilian harm continued even after military operations were underway, despite pressure from the general public, the House of Commons and other government departments. When questioned about the mounting toll of civilian deaths during a debate on April 2, 2003, the armed forces minister responded by claiming that the MoD has ‘no way of ascertaining the numbers of military or civilian lives lost’. The following day, he also claimed that ‘it is impossible to know for sure how many civilians have been injured, or killed and subsequently buried’. But when the defence secretary echoed these points in a debate later that year, an official at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) reported that:

Notwithstanding this answer, records are kept of all significant incidents involving UK forces. A significant incident would include… a soldier wounding or killing a civilian. At present, this information is not collated, although PJHQ [Permanent Joint Headquarters] accept that it could be (p186).

The MoD was also facing criticism about the lack of civilian casualty data from other government departments, with the foreign secretary writing to his counterpart at defence to warn that the current tactic of dismissing all inquiries about collateral damage ‘leaves the field entirely open to our critics and lets them set the agenda’. What concerned him was not so much the human costs of the conflict but the negative press that they were generating. The government needed to find ways, he argued, of ‘countering the damaging perception that civilians are being killed needlessly, and in large numbers, by coalition forces’ (p187).

The debate about whether or not the MoD should be keeping track of civilian deaths continued to rumble on as the conflict progressed and escalated quite dramatically after the Iraq Body Count (IBC) argued that civilian deaths might have passed 10,000. In late April, Blair asked for clarification on the number of civilians killed, stating that ‘the figure of 15,000 is out there as fact – is it accurate?’ The following month, No. 10 requested a weekly digest of casualty figures (although there is no evidence that one was ever produced). Again, the government’s concern was largely about public perception rather than human life (p190). As one memo makes clear: ‘the Prime Minister is concerned that we are not getting the message across effectively enough about the extent of insurgent/foreign terrorist responsibility for civilian deaths’ (p191). But the MoD responded by stating that it did not have an accurate methodology for calculating collateral damage, whilst Blair’s Private Secretary warned the FCO was also worried that a cumulative total might show that the ‘MNF [Multi-National Force] are responsible for significantly more [casualties] than insurgents/terrorists’ (p193). Moreover, there was also concern about the politics of assigning responsibility for incidents involving civilian casualties, with the FCO unwilling to go on the record and say that coalition partners might have been responsible for a specific attack. Nevertheless, the report is pretty damning in its conclusions, stating that more time was ‘devoted to the question of which department should have responsibility for the issue of civilian casualties than to efforts to determine the actual number’ (p218).

What is particularly curious about this failure is the government did set up a trial monitoring exercise to see whether or not it was possible to collate information about civilian casualties from both public and military sources but this process was never completed (p193). In late 2004, Blair’s Private Secretary advised him that he would ask the Cabinet Office to initiate a trial period to monitor daily statistics on civilian casualties in order to assess how ‘credible (and helpful) the information would be’. If successful, he argued, the government could look at ‘outsourcing [the task] to a credible external organisation (e.g. a think tank or academics)’. At a meeting of the Cabinet Office on October 22, 2004, officials agreed that it was important to ‘quantify, as precisely as possible, the number of civilian deaths caused by a) insurgents and b) coalition military action’ (p194). The officials also decided that the best way to complete this task would be for the FCO to collect data from open sources, the MoD to collate military reports and PJHQ to analyse US statistics. The MoD was not best pleased with this development and wrote to the Cabinet Office to reiterate its concerns about the methodology and to warn that the public might start to expect this sort of analysis as a matter of course ‘no matter what the intensity of operation’. An official from the FCO was also concerned that if they made any amendments to figures taken from public sources it might give the impression that the government considered this data to have some reliability when its public position was that the data was not credible (pp194-195). Again, departments seemed to spend most of the trial period arguing about why the figures couldn’t be produced or why other departments should be responsible for producing them.

Although the government was reluctant to keep track of civilian harm itself, a number of body counts were produced during this period in an effort to document the human costs of conflict. The report reveals that there was an interesting disconnect between the government’s public statements on this data and its internal assessment. When The Lancet published the results of the first mortality study in 2004, which found an excess of 98,000 deaths based on a survey of 988 households in 33 clusters, the MoD asked its Chief Scientific Advisor (CSA) to conduct a review of its findings. He concluded that the results of the study and the methods used were ‘probably as robust as one could have achieved in the very difficult circumstances’ and advised the government to ‘proceed with caution in criticising the paper’. But despite his cautions, Blair told the House of Commons a few days later that he ‘did not accept the figures’. His Private Secretary also wrote to the FCO, telling them to develop a ‘quicker and more forceful response to claims about civilian deaths that we regard as founded’ (p197). However, when officials in the FCO reviewed the paper they too concluded that ‘the statistical methodology appears sound’ and warned that any reasons they had to doubt the validity of the figure could also be used to suggest that the actual number of deaths might be significantly higher. Despite going to great lengths to discredit them, the report shows that officials could find little wrong with either the methodologies used or the data produced.

Similar discussions took place when The Lancet published a follow-up study in 2006, which found that there had been 654,965 excess deaths based on a survey of 1,849 households (almost double the original sample). Even though a government spokesperson had told reporters that this figure ‘was not one we believe to be anywhere near accurate’, internal memos reveal that they could find little wrong with the study. The MoD’s CSA reviewed the new study and advised that ‘the study design is robust and employs methods that are regarded as close to best practice in this area, given the difficulties of data collection and verification in the present circumstances’. This put the government in the strange position of being both fully confident on the methodology used in the study but against the results that were found. As one official put it:

The figures are extraordinarily high and significantly larger than the figures quoted by the Iraq Body Count or Iraqi Government – however the survey methodology used here cannot be rubbished, it is a tried and tested way of measuring mortality in conflict zones’ (p209).

Rather than continue to rubbish the survey data, the report indicates that the government simply changed tack and focused on blaming the enemy for civilian deaths. As Blair argued in response to one question in the House of Commons: ‘it is correct that innocent civilians are dying in Iraq. But they are not being killed by British soldiers. They are being killed by terrorists and those from outside who are supporting them’.

***

The report concludes that the government could have and should have done more to monitor civilian harm during the early stages of the conflict and is critical of attempts by different government departments to shirk their responsibility. It is also unequivocal in its view that the government has a legal obligation to ‘make every reasonable effort to identify and understand the likely and actual efforts of its military actions on civilians’, including the direct harm caused by military operations and the ‘indirect costs on civilians arising from worsening social, economic and health conditions’ (p219). In keeping with the overall tone of the report, the section on civilian casualties is surprisingly candid in its criticism of the government’s approach to the war in Iraq. But it is also true that the lived pain and suffering of ordinary Iraqis tends to disappear into the background, with very little discussion about the lived experiences of those killed and injured on the battlefield. Perhaps what will be most useful about the report is the cache of previously unrealised documents that accompanies the report, which will undoubtedly tell us a lot about the targeting procedures that were in place, the battlefield damage assessments that should have been undertaken and the way in which the military understood its legal obligations around civilian harm. However, the vast majority of these documents still remain classified, limiting our understanding of the rules and regulations that were in place.

Tom Gregory is a lecturer at in the department of Politics & International Relations at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. His research focuses on contemporary conflict, critical security studies and the ethics of war.

0 Comments