In my last post, I lamented that Donald Trump is the presumptive GOP nominee, despite his outrageous series of slurs against different groups, his lies, and unscrupulous business practices. Before exploring what arguments might persuade Republicans and undecideds to vote against Trump, what other substantive objections are there to Trump?

Trump has policy stances and utterances, based on some gut check about what outrageous thing might rile a receptive audience and keep him in the news so that he doesn’t have to pay for TV ads. His style is based on improvisation and pandering, so he flip-flops as needed. It’s unclear that there is a core belief other than Trump will do or say what he thinks is necessary to benefit Trump. There are signs on foreign policy that he has a consistent take on the world which is America is a sucker and should stick it to the other guys.

Trump and Domestic Policy

Trump’s embrace of the most extreme positions on immigration, abortion, guns and domestic policy seems opportunistic. These episodes invariably show Trump misunderstands the nuances of conservatism. When he says let’s punish women who get abortions, he gets push back from anti-abortion foes. When he says guns in bars would have prevented Orlando, the NRA steps out and says Donald has gone too far (the NRA!).

Trump here has a record of having supported liberal causes in the past and has avoided Republican dogma by praising Planned Parenthood in the debates. Here, I think Trump doesn’t have a core set of beliefs. On some level, that might make him a moderate. However, because he’s not governed by principle but opportunism, he’s just as likely to go in a reactionary direction as he has done in taking a hard-line pose on immigration. Whether he is merely pandering to racist sentiment on the right doesn’t really matter, unless you think a President Trump won’t be at all captive to atavistic forces he’s unleashed during his campaign. I don’t think I want to find out.

Trump on Foreign Policy

Intervention and Opportunism. On foreign policy, I see Trump as most opportunistic when it comes to military intervention. He has tried to take credit for having opposed the Iraq War, though that doesn’t appear to be true. At the same time, he has lambasted the Obama Administration for failure to respond adequately to ISIS.

At times, he’s disavowed military intervention and at other moments embraced a more vigorous presence in the Middle East, suggesting that U.S. ground troops would be required:

“We really have no choice. We have to knock out ISIS,” he said. “I would listen to the generals, but I’m hearing numbers of 20,000 to 30,000.”

When pressed about this by the Washington Post, Trump backtracked:

I find it hard to go along with—I mention that as an example because it’s so much. That’s why I brought that up. But a couple of people have said the same thing as you, where they said did I say that and I said that that’s a number that I heard would be needed. I would find it very, very hard to send that many troops to take care of it.

On Libya, he said the world would have better leaving Gaddafi in power and then later said he supported surgical strikes to remove him. So, here, I think Trump is trying to have it both ways. Who knows what he would actually do.

There is an important debate to be had here about the wisdom of military intervention and America’s role. Interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya suggest that state-breaking is easy but state-building is hard. Whether a more limited set of goals in any of these conflicts would have been wise or achievable is debatable. Other interventions in the Balkans and West Africa have had more positive outcomes. What should we take away from these various episodes? Of one thing I’m sure, Donald Trump and his coterie of hangers-on are ill-equipped to face and have these discussions.

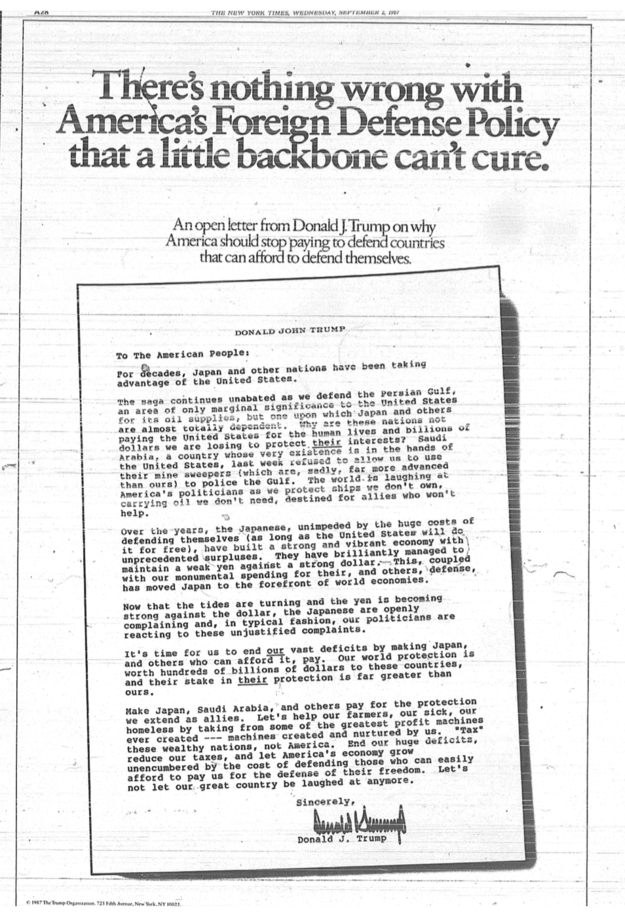

America is a Sucker. Others such as Tom Wright have examined his thirty plus years of public statements and concluded Trump has consistent core beliefs, which are based on a mercantilist zero-sum logic. This attitude was on offer in a 1987 full-page ad Trump paid for in the New York Times.

In Trump’s world, deals are made and only one side wins. In his view, the U.S. has consistently been getting bad deals with the Europeans, Japanese, Chinese, and Iranians.

Trump has long believed the United States is being taken advantage of by its allies. He would prefer that the United States not have to defend other nations, but, if it does, he wants to get paid as much as possible for it.

From this inclination to see the U.S. getting a raw deal from foreign partners comes Trump’s views on alliances and trade. If others don’t want to pony up more to support NATO, Trump’s fine with dumping it. Similar for relationships with Japan and Korea.

While President Obama has expressed concern about burden-sharing by allies, Trump takes this to another level, cavalierly suggesting that the post-WWII liberal order should be replaced by open revisionism by the U.S. to ensure that we win and others lose, as if there is no scope for joint gains.

In his interview with the Washington Post, Trump captured this sense of we’re too broke to afford international commitments and leadership:

No, I don’t want to pull it out. NATO was set up at a different time. NATO was set up when we were a richer country. We’re not a rich country. We’re borrowing, we’re borrowing all of this money. We’re borrowing money from China, which is a sort of an amazing situation. But things are a much different thing. NATO is costing us a fortune and yes, we’re protecting Europe but we’re spending a lot of money. Number 1, I think the distribution of costs has to be changed. I think NATO as a concept is good, but it is not as good as it was when it first evolved. And I think we bear the, you know, not only financially, we bear the biggest brunt of it.

In his interview with the New York Times, Trump’s views on defense and trade come back to this sense of American decline and being ripped off:

But we defend everybody. When in doubt, come to the United States. We’ll defend you. In some cases free of charge. And in all cases for a substantially, you know, greater amount. We spend a substantially greater amount than what the people are paying. We, we have to think also in terms – we have to think about the world, but we also have – I mean look at what China’s doing in the South China Sea. I mean they are totally disregarding our country and yet we have made China a rich country because of our bad trade deals. Our trade deals are so bad.

I’m still of the view that Trump is badly misinformed about the virtues of the liberal order and the contributions our allies make to their own defense. While there are kernels of truth in Trump’s critique (on burden-sharing, for example), Trump’s vision of a defensive America beaten down by bad deals misunderstands how the world order has worked to the U.S. advantage.

Trump Tapping in to the Zeitgeist on Trade. In the economic realm, Trump, like Bernie Sanders, is trying to tap in to economic anxiety of the working class, particularly the white working class. In a speech this week, he dumped on NAFTA and China’s entrance to the WTO:

NAFTA was the worst trade deal in history, and China’s entrance into the World Trade Organization has enabled the greatest jobs theft in history.

Looking ahead, he suggested that the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12 country Pacific Rim trade agreement, would spell the death of U.S. manufacturing and U.S. influence:

The TPP would be the death blow for American manufacturing.

It would give up all of our economic leverage to an international commission that would put the interests of foreign countries above our own.

I’m not going to litigate NAFTA and the WTO, though I generally think trade has been good for the global economy, particularly in lifting millions of people in the developing world out of poverty, though the gains haven’t been shared equally and losers haven’t been sufficiently compensated.

Leaving that aside, as Dan Drezner has argued, Trump’s trade views are at odds with Republican orthodoxy on free trade, though they capture some of the current popular zeitgeist against trade deals (though this se ntiment may actually fail to capture the reality of public opinion if polls are to be believed).

ntiment may actually fail to capture the reality of public opinion if polls are to be believed).

However, what Trump is offering isn’t likely to make the situation better. As Drezner notes, protectionism isn’t going to bring jobs back to America lost through automation:

To repeat a point I’ve made before (and will have to make again because this is a powerful myth), the truth is that while a small fraction of American manufacturing jobs migrated overseas over the past few decades, a far greater fraction of manufacturing jobs simply disappeared and are not coming back. The far bigger driver of these job losses is the creative destruction that comes from technological innovation and productivity increases.

This is a point President Obama made last week in remarks in Canada who went on to argue that protectionism isn’t the answer:

And the prescription of withdrawing from trade deals and focusing solely on your local market, that’s the wrong medicine — first of all, because it’s not feasible, because our auto plants, for example, would shut down if we didn’t have access to some parts in other parts of the world. So we’d lose jobs, and the amount of disruption that would be involved would be enormous. Secondly, we’d become less efficient. Costs of our goods in our own countries would become much more expensive.

Working class grievances about inequality and the economy are real. Trade and globalization may partially be responsible for some of the negative economic impacts on lower wage workers. Economists such as Paul Krugman admit the opening up of markets to China has been a world historical phenomenon with unanticipated consequences:

One widely-cited paper estimates that China’s rise reduced U.S. manufacturing employment by around one million between 1999 and 2011.

Krugman also thinks the future gains from further trade liberalization aren’t all that large and that if we’re not prepared to compensate the losers of trade deals, we may be better off pushing the pause button. Similarly, Dani Rodrik thinks that mutual lowering of trade barriers at this point causes more problems than it solves. He suggests that future trade agreements should carve out more development space for poor countries and widen the allowable safeguards to protect domestic social norms in rich countries.

Again, there is an important argument to be had here but as Krugman notes, Donald Trump wants to turn back time but doesn’t seem to have answer for the future:

But America is a big place, and total employment exceeds 140 million. Shifting two million workers back into manufacturing would raise that sector’s share of employment back from around 10 percent to around 11.5 percent….

No matter what we do on trade, America is going to be mainly a service economy for the foreseeable future. If we want to be a middle-class nation, we need policies that give service-sector workers the essentials of a middle-class life. This means guaranteed health insurance — Obamacare brought insurance to 20 million Americans, but Republicans want to repeal it and also take Medicare away from millions. It means the right of workers to organize and bargain for better wages — which all Republicans oppose. It means adequate support in retirement from Social Security — which Democrats want to expand, but Republicans want to cut and privatize.

The Implications of Trump for World Order

Putting Trump’s statements on alliances and trade together, the significance of the Trump project for world order is not lost on Tom Wright who argues:

Simply put, Mr. Trump thinks America’s allies and partners are ripping it off and he wants out of America’s leadership role in the international order. Over and over again, Mr. Trump has questioned why the United States. defends Japan, South Korea, Germany and other nations without being paid for it. Just this week, he promised to significantly diminish U.S. involvement in NATO and when asked if America “gained anything” from having bases in east Asia he replied “personally I don’t think so”. This is not about a more equitable share of the burden, which many have called for. Mr. Trump believes that the U.S. gains little from having allies unless it is paid handsomely paid by them.

Wright’s summary judgment on Trump is similar to conclusions reached by others, that perhaps one of the greatest threats to global stability is Trump himself:

A Trump administration would pose the greatest shock to international peace and stability since the 1930s. This is not because Mr. Trump would invade other countries but because he would unilaterally liquidate the liberal international order that presidents have built and defended since Franklin Delano Roosevelt. If the word “isolationist” has any meaning, he qualifies as one….

To wit, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s assessment of the risks of a Donald Trump presidency is worth quoting in full:

Although we still do not expect Mr Trump to defeat Ms Clinton, there are risks to this forecast, especially given the terrorist attack in Florida in June. Thus far Mr Trump has given very few details of his policies – and these tend to be prone to constant revision – but a few themes have become apparent. First, he has been exceptionally hostile towards free trade, including notably NAFTA, and has repeatedly labelled China as a “currency manipulator”. He has also taken an exceptionally punitive stance on the Middle East and jihadi terrorism, including, among other things, advocating the killing of families of terrorists and launching a land incursion into Syria to wipe out IS (and acquire its oil). In the event of a Trump victory, his hostile attitude to free trade, and alienation of Mexico and China in particular, could escalate rapidly into a trade war – and at the least scupper the Trans-Pacific Partnership between the US and 11 other American and Asian states signed in February 2016. His militaristic tendencies towards the Middle East (and ban on all Muslim travel to the US) would be a potent recruitment tool for jihadi groups, increasing their threat both within the region and beyond, while his vocal scepticism towards NATO would weaken efforts to contain Russia’s expansionist tendencies. Elsewhere, and arguably even more alarmingly, his stated indifference towards nuclear proliferation in Asia raises the prospect of a nuclear arms race in the world’s most heavily populated continent.

No thank you.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

Thanks for doing this so the rest of us don’t have to.