This is a guest post by Ariel I. Ahram (@arielahram). Ahram is an associate professor in Virginia Tech’s School of Public and International Affairs and is the author of Proxy Warriors: The Rise and Fall of State Sponsored Militias (Stanford, 2011).

A few years ago the possibility that an American president would be complicit as armed supporters attacked members of opposition would have seemed far-fetched. Yet the alliance between president-elect Donald Trump and the so-called ‘alt-right’, a protean alignment of nativists, xenophobes, Christian identarians, and white supremacists, raises this distinct fear. Right-wing militias are among Trump’s most vociferous supporters. Jay Ulfelder, a leading researcher on political violence, after the election opined that

American civil liberties are values-blind. We live in a society that tolerates the overt organization of armed groups committed to fighting the state and hurting other people. In some places, the lines between those groups and the state blur. Under those conditions, it seems sensible to prepare against the worst.

Examining global trends in the rise of pro-government militias, as well as the history of vigilantism in America, suggests that the worst may be yet to come. Collaboration between the presidency and armed non-state actors jeopardizes the quality of American democracy and its political institutions overall. Still, there are measures that can help prevent the erosion of the rule of law.

Many Years of Voting Dangerously

From Mosul to Manila, the world has seen many governments outsourcing control over violence to non-state actors. This phenomenon seems to contradict a core theory of how states behave. The famed German sociologist Max Weber defined a state as an entity that claims the “monopoly over the legitimate use of force.” The police, army, and other official security forces are the singular core of state activity. Pro-government militias, vigilantes, and paramilitaries work on behalf of the state, but outside its legal bounds. It is commonly presumed that only dictatorial or dysfunctional states would resort to recruiting militias. Yet Sabine Carey and her collaborators have demonstrated that militias are both prevalent and variegated, present in over eighty-eight countries around the world.

Democracies, including the United Kingdom, India, and Italy, are no strangers to militias. Elections and militia violence often go hand-in-hand, as Paul Staniland points out. Political elites recruit violent entrepreneurs—men (almost exclusively) with expertise in coercion. Sometimes gangsters and criminal networks serve as politicians’ hired hands, but army and police veterans have also appeared in pro-government militias. Bands of demobilized soldiers wreaked havoc in electoral politics and doomed the nascent democratization across Europe after World War I. While governments maintain plausible deniability, militias harass voters and assault the opposition. This does not spell a collapse into anarchy. Rather, pro-government militias indicate a shift from rule of law to “rule by law.” Law enforcement becomes unpredictable, unfair, and biased toward maintain regime control.

Democratic Decline and Militia Ascent in America

Militias are embedded in America’s political DNA. The Second Amendment of the Constitution prescribes the right to bear arms for the purposes of maintaining a “well-regulated militia.” The freedoms of speech and assembly give militias further space to operate. Yet, this seeming ingrained trait has been expressed differently at different times. During the nineteenth century, private militias played critical roles in the subdual of Native Americans, suppression of African-Americans, and crushing labor unrest. Jonathan Obert describes how America’s modern, professional police and the national guard forces emerged alongside private armies, posses, and vigilante forces and often worked together to mutual benefit.

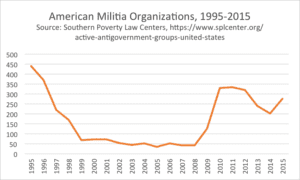

The contemporary incarnation of the American militia movement draws its roots from right-wing and fringe libertarian groups like the John Birch Society and white supremacists like the Ku Klux Klan, but evolved in the 1990s into a more eclectic ideology premised on distrust of “the Establishment,” millenarianism, xenophobia, and racial resentment. The most comprehensive sources of data on militias comes from watchdog organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center. Despite some problems in data collection, state-by-state and case study analyses identify two key drivers of militia activity: social dislocation, such as the perceived threat to male supremacy derived from growing female labor participation rates, and economic distress, particularly in agricultural regions. The SPLC data show a dramatic expansion of militia activity under the presidency of Barack Obama, who was widely depicted as socially degenerate and traitorous in right-wing circles. In sum, militias groups combine resentment toward the government with an intense attachment to an imagined America that is white, Christian, rural, and patriarchal.

The efflorescence of militias in America fits a striking global pattern: it arrives during a period of decided democratic decline and loss of confidence in democratic institutions. The militia movement drew moral authority from standing astride what it deemed a tyrannical state. The war on terror played an important part in accelerating radicalization. On one hand, the September 11th terrorist attacks catalyzed Islamophobic and xenophobic trends in American culture. On the other hand, the conduct of the war itself played into narratives about America becoming an oppressive police state that overrode civil liberties and (especially) gun rights. The U.S. military itself has become an incubator to violent entrepreneurs. Street gangs and white supremacists groups have both sought to infiltrate military ranks in order to gain access to arms and training. Though small in absolute numbers, ex-servicemen have been implicated in plotting and carrying out several violent attacks in recent years.

Law enforcement agencies have long expressed concern about the threat of right-wing militia groups. Still, militias have invented pretexts of American national security as justification for violence. For example, in October three Kansas men associated with a militia group called Crusaders were arrested for plotting to bomb an apartment building housing Somali refugees, as well as local government officials, and refugee aid organizations. Their aim was to “wake people up” to the danger of Islam.

The 2016 election punctuated the fragility of America’s democratic institutions. Protests and counter-protests continue; the prospect of violence looms. The fact that the Electoral College winner is different from the popular vote winner for the second time in five electoral cycles only underscores the democratic deficit. In the midst of this democratic decay, Trump’s stance on militias is equivocal. Though he attended New York Military Academy, draft deferment kept Trump out of the service in Vietnam. Beside misogyny (which is rife within the alt-right), Trump shows little personal proclivities to firearms, outdoorsmanship, Christianity, or other aspects of militia sub-culture. During the primaries, Trump condemned the armed take-over of federal land in Oregon, stressing the need “to maintain law and order, no matter what.”

Nevertheless, militia groups and the far right-wing organizations have gravitated to Trump’s banner. The head of Trump’s veterans outreach initiative in New Hampshire pled guilty to conspiracy after joining the Oregon standoff. In the days before the election a Georgia militia group took up field training exercises. During the general electoral campaign supporters set up their own militia to defend Trump’s rallies from alleged violent left-wing agitators. Journalists deemed anti-Trump were barraged with death-threats. Trump encouraged violence throughout the campaign.

Since election day the SPLC documented a dramatic increase in hate crimes targeting immigrants and minorities. Trump has condemned racism, albeit tepidly. He has also, though, directed insults and taunts at news organizations, union leaders, corporations, and the cast of a Broadway musical. Some commentators see this as intending to distract from evidence of corruption within his incipient administration. But these declarations can also help to paint the target for future attack. Recent violence stemming from so-called “fake news” stories set a troubling precedent.

Learning to Live with Militias in America

America’s right-wing militias depict themselves as carrying forth the libertarian legacies of the revolutionary era but the more recent history of militias in America has been anything but emancipatory. On the contrary, militias reinforced ethnocratic domination and economic hierarchies at odds with principles of equal protection and democracy. The current incarnation of militias is no exception.

How long can Trump continue to ride the militia tiger? Some voices in the alt-right already feel betrayed by his apparent softened tone on immigration and appeasement of centrist Republicans. Still, these groups are vital to Trump’s electoral success and it is unlikely that he will disavow, much less prosecute, militias if it costs him politically. It therefore falls to state and local officials and civil society to maintain the bulwarks of institutional integrity. Several states have laws regulating paramilitary-style training in weapons and armaments. Though state officials have rarely used these statutes, they could be necessary if federal authorities demure. Additionally, private citizens and organizations can monitor the activities of violent groups. Overall, though, the outlook is hardly sanguine. A tacit alliance between the would-be president and armed militia groups raises profound concerns about the impartiality of justice and equal protection. It puts America at risk of becoming a nation ruled by law, rather than of it.

Jarrod Hayes is an Associate Professor of International Relations at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. His research interests include the IR theory, social construction of threat, societal mechanisms of security within democracies, and the social construction of environmental problems. His first book Constructing National Security: US Relations with India and China was published in 2013 by Cambridge University Press and his second, an edited volume entitled Constructivism Reconsidered, was published by University of Michigan Press 2018. He has published articles in numerous scholarly journals including European Journal of International Relations, Foreign Policy Analysis, Global Environmental Politics, International Affairs, International Organization, International Studies Quarterly, Nonproliferation Review, and Security Studies.

0 Comments