The following is a guest post by Emily Hencken Ritter, Assistant Professor at the University of California, Merced.

Like so many, my heart and mind aches for the loss Will Moore’s death represents to humanity. He was as much a mentor to me in grad school and my career as if he had been on my dissertation committee. He supported me, critiqued my work, told me to be bold, and showed me I could be myself. Perhaps the most special thing he gave me was an example for generating bigger conversations. I attended conference after conference that he hosted not to present papers in panels but to get people to think outside of boxes and talk to one another. Will taught me about the community of science. His absence is so much greater than my loss.

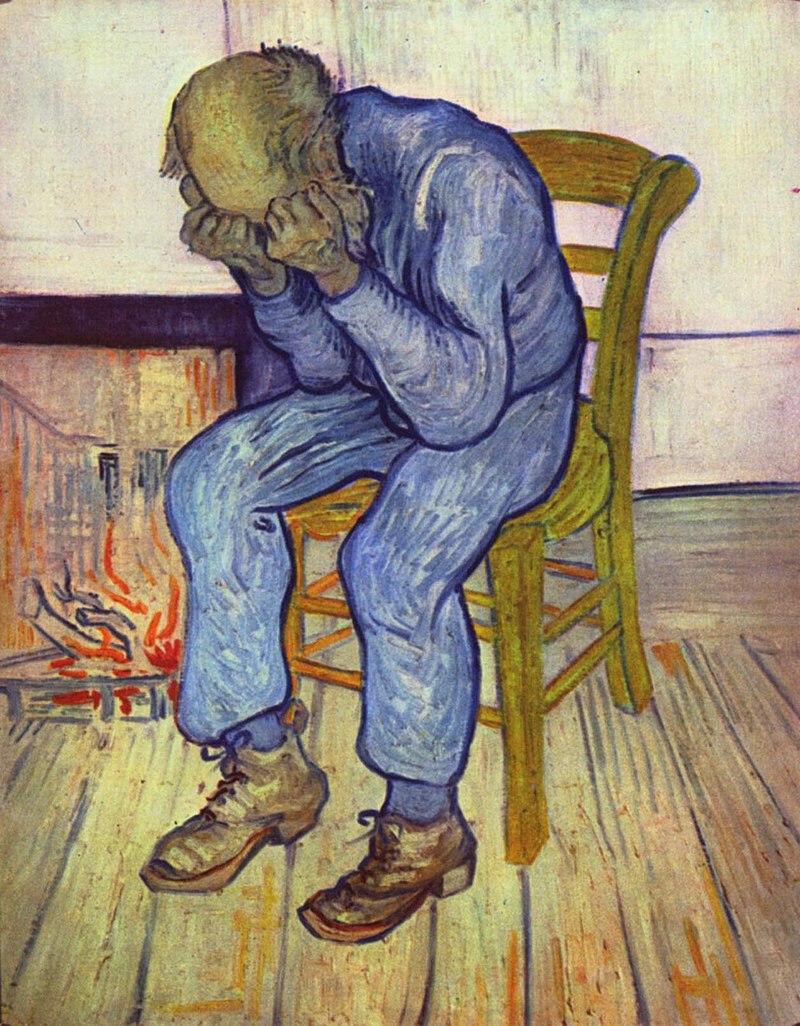

One way that Will continues to help all the people he touched is by stimulating conversations about mental illness. I want to assist in this effort and be honest, as Will was, so that his scientific community can innovate in mental health as much as peace research.

I have struggled with severe depression disorder for three years. By severe depression, I mean “a period of more than two weeks” in which I suffered many of the symptoms of depression: low mood, extremely tired but unable to sleep, low energy, hyper sensitivity to noise, frequent crying. I no longer enjoyed things that I have always loved: music, exercise, my work, my friends, my family. I couldn’t recognize myself.

Many things caused my brain to develop this disease, and no one thing is a definitive cause. Depression is in my genetics. I bear internal and external pressure to succeed. I work in academe, where rejection and harsh criticism are the norm. I’m on the tenure track, which carries pressures to work unreasonable hours. But lots of people have these things and are fine.

I became depressed when my child was born. I wanted very much to be a mother and raise a child with my spouse. But the social norms of motherhood clashed with my strong ideas that I would be defined by my research and not by my womanhood. I defined my identity so strongly with my ideas and productivity that I could not find a place in my identity to be a scientist and a mother. This left me without a sense of, or value for, myself.

Depression is hard to see. Not having had a child before, neither I nor my spouse knew that my being down and moody in the first year was unusual. I also tend to be a “high-functioning depressive”, in that I can still be productive, meet deadlines, give lectures, and be outgoing in social environments while being depressed, confused, lonely, and panicky internally.

Or, at least, I could for the first two years. But I worked too hard, traveled too much, and took care of myself so little that it all came crashing down last summer. I couldn’t motivate myself to work more than an hour at a time. I couldn’t make myself interact with others, even family. I slept too much, ate poorly, and stopped exercising. I cried throughout the day. I started to hate my job, hate my research, hate myself.

The crazy part is that I still produced research. There’s no gap in my CV. No one would have ever been the wiser about my dark clouds–except that I told them.

I asked everyone around me for support and assistance. I saw a therapist, was diagnosed, and began to take medication. This did not end my depression or anxiety, but it set the groundwork for me to help myself. [1]

I asked my co-authors to be patient with me, because I would be slow in writing, responding, and thinking. I asked my chair for relief from service so I could take care of myself. I asked my senior mentors at Merced and around the discipline for their ears, compassion, and advice. I asked my family for understanding. I asked my spouse, a million times, to hold me up.

Once people around me knew I was suffering, especially the ones I was accountable to, I no longer had to push it away. I gave myself permission to be depressed, and in doing so I gave myself permission to heal. I shifted my mindset to treat everything not as a reminder of failure but as a tiny success. Read three pages? Great work. Showered today? Heck yeah I did. I stopped working when I didn’t feel like it and did something for myself. I stopped seeing friends who weren’t as close and pulled my close friends in tight. I went on a California-hippie meditation retreat in the mountains. I shifted tiny victories into bigger ones. I found a version of myself I could love, and I’ve been a million times better in the last six months.

People like to know how they can help someone who is depressed. It helped when friends asked me what was wrong, even when I didn’t want to talk about it. Listened and empathized without trying to fix it. Volunteered to watch my kid or take on more of a project so I could have space. Extended deadlines and supported dropping out of a conference. Loved me and included me even though I thanked them and stayed home.

I defined, accepted, and shared my depression with others, so I could tell them when things helped or hurt. I could do this because I feel safe in my department, among my colleagues, and with my co-authors. I am honored to work in a unit with a culture of professional and social support, where families and personal lives are part of our professional relationships, and where people can be forthcoming and respectful. We celebrate each other’s victories and reach out when someone flounders. As a result, I could be honest when I couldn’t do something, ask for accommodations, and use my colleagues for support. They enabled me to get better, instead of disappearing altogether.

To be able to have this conversation about mental health in the discipline, we need to create safe havens in our offices and departments on many dimensions, for people of all types, so we can be who we are, depressed or not.

[1] Amanda Murdie gives great advice for those experiencing depression in academia. Every person is different and needs different things.

Amanda Murdie is Professor & Dean Rusk Scholar of International Relations in the Department of International Affairs in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Help or Harm: The Human Security Effects of International NGOs (Stanford, 2014). Her main research interests include non-state actors, and human rights and human security.

When not blogging, Amanda enjoys hanging out with her two pre-teen daughters (as long as she can keep them away from their cell phones) and her fabulous significant other.

Thank you for your courage, Emily. We are with you.

I want to second this: thank you for your courage. know that we are with you.

I really, really appreciate this. The whole way that academia feels like it discounts everything else, such as your familial and friendly relationships, is something I struggle with and feel like could be a source of depression for me. Mind you, I’m a graduate student, but already I’ve had to have the thought/conversation of “which is more important, my relationships or my love/pursuit of knowledge and science?”. That conflict really resonates (though I’m sure not the same as) with your experience of having a child and then being torn between motherhood and being a full scientist.

I love you, Emily! Thanks so much for sharing your story. You are my hero!

Sertaline, y’all. It’s good stuff. Taking it is way better than disappearing.

Thank you so much for your honesty and thoughtful words. I’ve had my own struggles–the catalyst being some marital problems and then being thrust into academia. I love my job–I get to teach at my Alma Mater–a small private school. So, we aren’t forced to research, but teach a heavy course load. Anyhow, thanks for your post.

Powerful post, Emily. Thanks so much for sharing this.

Some of Stephen Brookfield’s books on teaching include stories of his making teachable moments out of his struggles with depression. Like your post, worth reading. Peace – JR