The following is a guest post from Jennifer Spindel and Robert Ralston, Ph.D. Candidates in Political Science at the University of Minnesota.

On 26 July 2017, Donald Trump announced, via Twitter, that the US Government would “not accept or allow transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the US military.”[1] Notably, the tweets were sent exactly 69 years after President Harry Truman issued the order to integrate the US military. Even if Trump’s tweets do not lead to formal policies, they exemplify the narrative that “others” would disrupt cohesion, thus would negatively affect the military’s ability to win “decisive and overwhelming victory.”

The narrative that social cohesion is the primary determinant of military effectiveness – and thus must be protected at all costs – has recurred throughout history. This rationale for exclusion provides narrative cover for policies of formal and informal national discrimination. In reference to racial integration, the US Navy stated, “past experience has shown irrefutably that the enlistment of Negros (other than for mess attendants) leads to disruptive and undermining conditions.” And yet, the military integrated in July 1948, with no subsequent disruption to cohesion or effectiveness.

Similar arguments were made in the mid-1990s, as Congress debated repealing the policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell.” As political scientist Elizabeth Kier shows, high-ranking military officers feared that open service by gay individuals would disrupt military cohesion. Army Chief of Staff General Gordon Sullivan said, “the introduction into any small unit of a person whose open orientation and self-definition is diametrically opposed to the rest of the group will cause tension and disruption.” General Colin Powell similarly believed that gay soldiers would disrupt social cohesion, and that this would negatively affect the army’s ability to win wars. He explained: “we create cohesive teams of warriors who will bond so tightly that they are prepared to go into battle and give their lives if necessary.” And yet, in 2010 Congress repealed “don’t ask, don’t tell”, with no subsequent disruption to cohesion or effectiveness.

Arguments about social cohesion and military effectiveness persist today. Representative Vicky Hartzler (R-Missouri) has argued that “military service is a privilege, not a right. It is predicated on the singular goal of winning the war and defeating the enemy.” Representative Mac Thornberry (R-Texas) said that the decision to allow transgender soldiers prioritized politics over policy. Drawing connections between these arguments and past policies of exclusion, Representative Donald McEachin (D-Virginia) said, “…a Congress 70 or 80 years ago that said that a certain group of people weren’t smart enough to fly airplanes, that they run at the first sign of battle, and that African Americans could not serve in the United States Armed Forces. Well, African Americans proved them wrong.”

At its heart, the debate about transgender soldiers is another debate about the “appropriate” roles of individuals in a democratic society. As Krebs argued, military service is often the vehicle through which marginalized groups can make claims for first-class citizenship. He writes, it was not “accidental that post-war African American claims for first-class citizenship were predominantly framed around battlefield sacrifice.” In democratic societies, minority groups have used the ideal and narrative of the citizen-soldier, the willing sacrifice of the individual in defense of the nation, to forward claims to first-class citizenship. In Janowitz’s formulation: “[The citizen soldier] is not a marginal person. Instead, with the completion of his military service, his citizenship status is enhanced.” Military service creates hierarchies of citizenship, and narratives about cohesion and military effectiveness remain rhetorical devices that serve to undermine claims to first-class citizenship.

To determine the causes of social cohesion and its connection to military effectiveness, we fielded a survey of 151 active duty and veteran US military personnel. We used open-ended questions that asked soldiers to define terms and discuss concepts in their own words. By asking soldiers themselves to explain these concepts, we provide the theoretical grounding to show that narratives about cohesion are political, not technical.

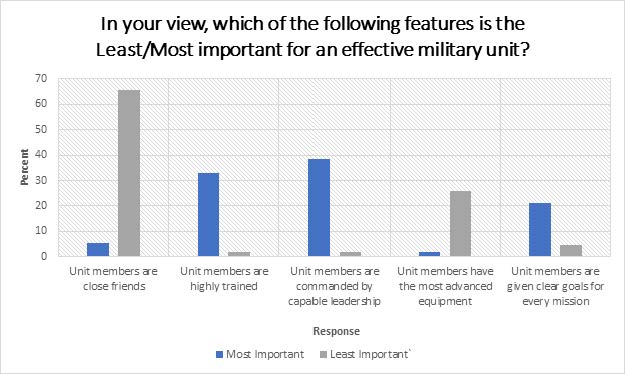

We asked, “In your view, which of the following features is the most important for an effective military unit.” Respondents identified capable leadership and highly trained units as the most important features of military units. Meanwhile, “unit members are close friends” was option that was deemed least important by respondents, by and large. This suggests that a primary aspect of social cohesion—close friendship—is largely seen by respondents as an unimportant dimension of military effectiveness. Though respondents were split over what feature was most important, there was consensus that social cohesion was the least important feature for an effective military unit.

More revealing were the responses to our open-ended questions. Respondents defined cohesion differently; some pointed to very traditional conceptions of social cohesion, such as this respondent:

“No matter where you are at, or how long you have been at a duty station there is a feeling of family. Yes, there are people who don’t get along with each other, but that is not the norm. You are never a stranger, or let someone be a stranger.”

For this respondent, cohesion is about a sense of togetherness, one that transcends friendship or getting along with each other, but rather is a duty to one another. It does not depend, as some scholars have argued, on sustained togetherness, according to this respondent.

Participants in our study who defined cohesion as something akin to task cohesion focused on the ability of a group to achieve a common goal or to complete a given task. Take, for example, this respondent, a sailor, who defined cohesion in task-related terms:

“It has a number of meanings, but everyone, ultimately has to work towards a common goal. The job, whatever it is, simply has to be done. I don’t care whether that is something as simple as sweeping the deck or as advanced as launching a tomcat off of a carrier deck in rough seas. I didn’t get to choose whether I did the job or not, but it simply has to be done. I’m not getting off topic here. Everyone in a unit, has to act towards getting the job, or mission, done.”

Others were pithier in their definitions, including one respondent who simply stated: “Get shit done.” Further, respondents distinguished between task and social cohesion, implicitly, in their responses. For example, one respondent defined cohesion as: “having your team members’ back (whether you like them or not.).”

We then asked whether they supported various inclusive policies, and what, if any, effect these policies would have on a sense of “togetherness.” We found that support of inclusive policies is correlated with political ideology: moderates and liberals were more likely to strongly support such policies, and believed they would have a positive effect on social cohesion. Conservatives, on the other hand, were less supportive of inclusive policies and believed they would have a negative effect of togetherness.

Notably, our analysis on transgender inclusion shows that there is no correlation between supporting that policy and the perceived effect of inclusive policies on togetherness. Whereas those who were unsupportive of including transgender soldiers believed it would negatively affect togetherness, those who supported including transgender soldiers were split on whether it would negatively or positively affect togetherness.

Our research builds on existing literature showing that arguments about inclusion and effectiveness are primarily political, not technical arguments. Those who have served in the military believe leadership, training, and clear mission guidelines are more important than social cohesion, and where they do believe cohesion is important they conceptualize it as task-based. As in the past, political debates about military inclusion and unit cohesion bear little resemblance to the factors that matter for service members. Evidence that inclusive policies make for military weakness is hard to come by. The narrative is neither new nor convincing.

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2017/07/26/trump-announces-ban-on-transgender-people-in-u-s-military/?hpid=hp_no-name_no-name%3Apage%2Fbreaking-news-bar&tid=a_breakingnews&utm_term=.17f491826cde

Steve Saideman is Professor and the Paterson Chair in International Affairs at Carleton University’s Norman Paterson School of International Affairs. He has written The Ties That Divide: Ethnic Politics, Foreign Policy and International Conflict; For Kin or Country: Xenophobia, Nationalism and War (with R. William Ayres); and NATO in Afghanistan: Fighting Together, Fighting Alone (with David Auerswald), and elsewhere on nationalism, ethnic conflict, civil war, and civil-military relations.

0 Comments