This is a guest post by Ardeshir Pezeshk, a PhD Candidate at University of Massachusetts specializing in civil wars, conflict-affected civilians and international law. Follow him on Twitter here.

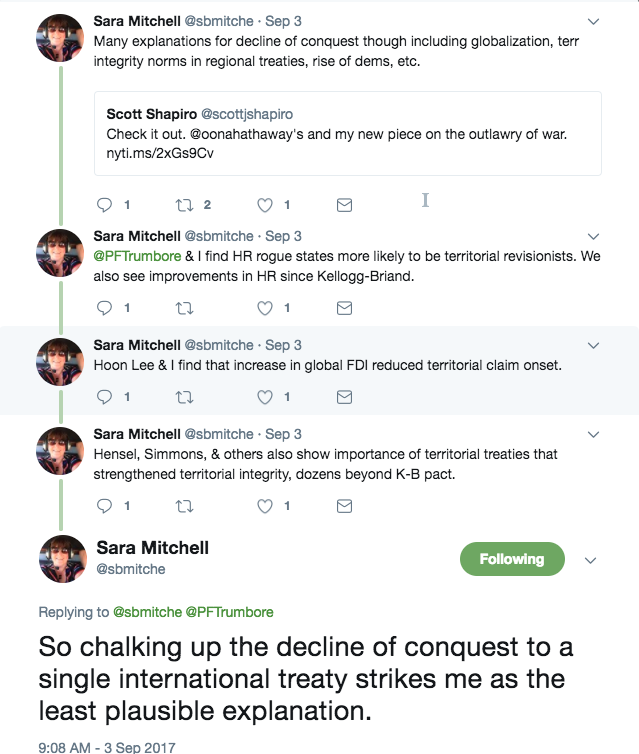

In an op-ed published in the NY Times over the weekend, Oona A. Hathaway and Scott J. Shapiro argue that the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928… worked. While they concede that the Pact did not succeed in its aim to end all war, the Pact was “highly effective in ending the main reason countries had gone to war: conquest.” But was it? According to International Relations Twitter, not really:

These reactions and the article itself are interesting for a few reasons. First, Altman seems to challenge the very idea that wars of conquest have significantly declined due to issues with COW’s Territorial Change data, the most important being omitting failed attempts to seize territory. If Hathaway and Shapiro’s study omits wars fought to gain territory but the conflict ended without territory changing hands, there may not be a puzzle needing explaining in the first place. That said, Hensel, Allison, and Khanani do account for attempts to forcibly acquire territory and link the decline of wars of conquest to territorial integrity norms.

However, even if we assume that conquest as a reason for war is falling by the wayside, factors other and perhaps more important than the Pact might explain the decline. As Mitchell tweets, the decline in wars of conquest have been chalked up to a number of factors including globalization, the character of liberalism and increases in the number of democratic states, regional and international treaties in which the territorial integrity norm is part, as well as rises in global foreign direct investment.

Third, Fazal suggests 1928 is the wrong starting point. Her research on state death suggests 1945 makes more sense. Zacher, too, argues the “acceptance stage” of the territorial integrity norm “began with the adoption of Article 2(4) in the UN Charter” in 1945.

What’s most striking, both in the article and the reactions, is the inattention to the evidence offered to substantiate the claim that the Pact was “highly effective” in stopping wars of conquest. Hathaway and Shapiro’s strongest rejoinder to potential critics offering other explanations is that those explanations are “incomplete because they tacitly assume the idea of the pact that might no longer makes right” (emphasis added). Here, Hathaway and Shapiro admit that to the extent that the treaty worked, it did so indirectly as an idea that framed the very way states understood the purpose of war.

Despite suggesting a constitutive effect of the Pact, the evidence offered simply details the decline in conquest which could then be attributed to other factors that Mitchell notes in her tweets above. It’s not clear to me how a decline in the number of wars of conquest per year, the decline in the average size of territory taken, or even the rare incidence of wars of conquest illustrate that state understandings of the purpose and aims of war changed.

To be fair, I haven’t read the book and as Hathaway wrote to Fazal on twitter, maybe I’ll be more persuaded by the extended form of the argument there. I want to be persuaded. But for that I’ll have to wait until September 12th.

In the meantime, I’ll share what I will be looking for to see whether Hathaway and Shapiro are right.

- Attention to the broader normative environment in which the territorial integrity norm emerged, was understood, and how the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 fit into that environment: As Zacher suggests, territorial integrity became increasingly salient in the mid 19th-century. Was the pact the culmination of ideas regarding territorial integrity? A mid-point? What distinguished it from Article X of the Covenant of the League of Nations?

- Debates among and between policy makers at the domestic and international level regarding the purpose of war and the degree of legitimacy afforded to territory as a war aim. How does the language vary over time?

- References to the Kellogg-Briand Pact: to what degree did the institutionalization of the territorial integrity norm reference the Pact?

- Perceptions about the effectiveness of the Pact: If policy makers and statesman understood the pact as naive, how did the idea of proscribing territorial aggression decouple from the general proscription against war?

In other words, I’m looking for greater attention to process versus outcome.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

Joseph O’Mahoney’s 2012 GWU dissertation, the full text of which is available for download via Proquest, would seem, judging from its title, to be relevant to parts of this discussion.

(Sorry I don’t have time to say more right now.)