The following is a guest post by Jay Benson and Eric Keels. Jay Benson is a Researcher at One Earth Future (OEF), with research focusing on issues of peacekeeping, civilian protection and intrastate conflict. Eric Keels is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in Global Security at the Howard H. Baker Center and a Contractor with the OEF Research. His research focuses on international conflict management and democracy in post-war countries.

During the first year of the Trump administration, the United States government has initiated numerous changes to the United States’ foreign policy. Since his first year in office, this new administration has signaled a 2020 withdrawal from Paris Climate Accords, backtracked on international efforts to sustain democracy, antagonized traditional US allies, and proposed a 23 percent cut in funding for the State Department. In addition to these radical shifts, the new administration has also been highly critical of international peacekeeping. United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley has consistently questioned the efficacy of international peacebuilding efforts in fragile countries such as Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The U.S. is not alone in this criticism, as new allegations of peacekeeper misconduct has drawn criticism of the management of UN peacekeeping operations. Given these critiques of international peacekeeping and peacebuilding, it is important to understand what benefits, if any, are provided by sponsoring these missions.

Given the current political climate’s increasing hostility to peacekeeping, what do we know about its efficacy in containing conflicts and protecting civilians?

Despite these criticisms, international peacekeeping operations have played a key role in promoting durable security in many war-torn countries over the last two decades. This has been demonstrated through numerous studies on the efficacy of peacekeeping. Since Barbara Walter’s seminal work on commitment problems in civil war, many scholars of political violence and peacebuilding have largely taken a positive view on the efficacy of international assistance in providing durable security. Following the publication of Page Fortna’s work on the key role played by UN peacekeepers in preventing civil war recurrence, numerous studies emerged confirming these results. Work by Kyle Beardsley also provided evidence that peacekeeping may contain civil war violence, preventing the contagion of civil wars in troubled regions. Finally, numerous studies have been published over the last five years that demonstrate that UN peacekeeping missions deployed during, and after, civil wars substantially reduce the number of targeted civilian killings perpetrated by the incumbent government and various rebel groups.

Still, criticism remains over international peacebuilding missions, particularly with efforts to foster democracy in post-war countries as well as localized security cooperation and state-building. Many, but far from all, of these studies have been pioneered by in-depth, qualitative research by Severine Autesserre. For instance, the emphasis on promoting democracy in the aftermath of civil war has often led to disastrous consequences. International peacebuilding missions often advocate for elections despite persistent localized violence between aggrieved communities. The elections themselves often spur a renewal of violence between combatants, as militant groups (unhappy with the results at the polls) may simply return to war as a way to contest the peace process. This is exactly what occurred in Angola in 1992, where UNITA’s violent rejection of their defeat at the polls ushered in an even more intense phase of the war.

In addition, Autesserre has pointed to the discrepancy between national level peace initiatives (that often seem successful) and grassroots initiatives designed to foster conflict resolution. These “bottom up” approaches to peacebuilding are often undermined by international actors who are overconfident in their own abilities to resolve disputes, have poor assumptions about the agency (and capabilities) of local partners, and are unfamiliar with key issues in the communities they seek to help. While national level peace processes may be abetted by international assistance, subnational violence may persist (and even get worse) following peacebuilding efforts. This has led to a bifurcation in the results surrounding the efficacy of peacekeeping and peacebuilding initiatives: success at the national level, and ambiguity with regard to subnational violence.

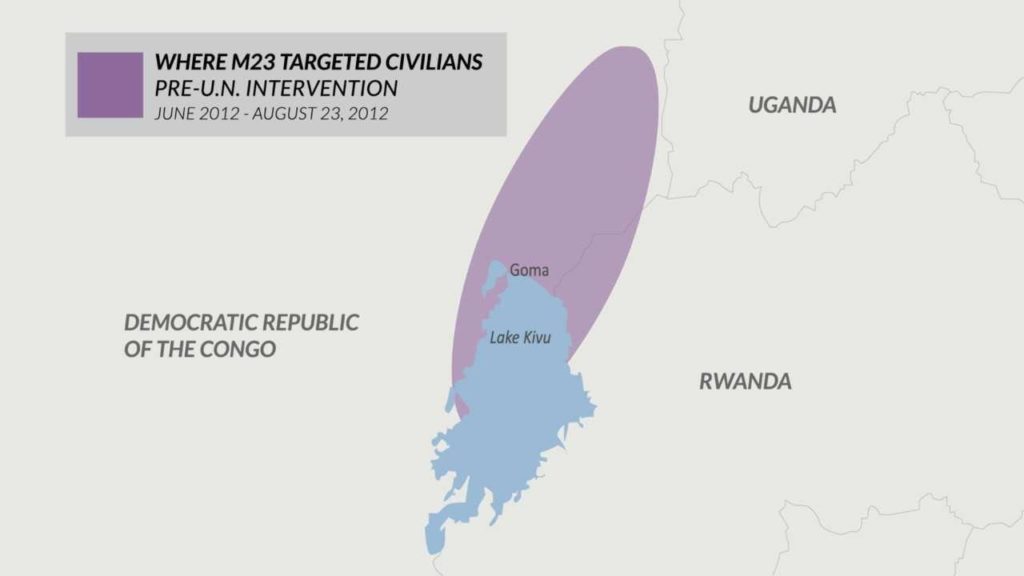

Interestingly, though, new research has emerged suggesting that changes within the UN’s mandate for peacekeeping have significantly increased the efficacy of peacekeepers in protecting civilians. Focusing specifically on the spread of subnational violence perpetrated by non-state actors, a new analysis by OEF Research suggests that peacekeepers may play a key role in containing the geographic scope of where armed groups target civilians. Looking specifically at cases of international interventions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria which actively target one party to a conflict, this research indicates violent non-state actors targeted by peace enforcement significantly reduce the area over which they target civilians. In the six cases examined, the area over which violent non-state actors most frequently targeted civilians fell by just over half after the start of intervention. It is important to note, though, that these operations had mixed success with regard to reducing total civilian casualties in the areas they targeted. This may have important implications for helping interventions define where to deploy troops and surveillance assets to best prevent and react to acts of civilian targeting.

Data Provided by OEF Research

Data Provided by OEF Research

How then do we square these two very different perspectives on the success of peacekeeping and peacebuilding more broadly? Taken together, the evolution on peacekeeping research largely points to two key conclusions. First, international peacekeeping/ peacebuilding efforts do play a key role in preventing atrocities against civilians when they aggressively seek to shield citizens from violence. This is not to say that there are not shortcomings in peacekeeping operations (specifically, abuses perpetrated by peacekeepers themselves), which the international community should work diligently to address. Second, peacekeeping and peacebuilding efforts may not be effective at enhancing the agency of local actors to ensure security or promoting good governance. It is important to note, though, that many of the challenges associated with good governance or the capabilities of local actors are highly complex. It may be overly ambitious to assume that peacebuilding missions can address these problems when, as astutely noted by Autesserre, international actors may not appreciate the complexity of these problems. While unfortunate, this should not detract from the first conclusion. Rather, the international community should value peacekeeping simply for the fact that the UN can play a vital role in protecting vulnerable communities from wartime atrocities.

Amanda Murdie is Professor & Dean Rusk Scholar of International Relations in the Department of International Affairs in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Help or Harm: The Human Security Effects of International NGOs (Stanford, 2014). Her main research interests include non-state actors, and human rights and human security.

When not blogging, Amanda enjoys hanging out with her two pre-teen daughters (as long as she can keep them away from their cell phones) and her fabulous significant other.

0 Comments