Tom Nichols, he of Death of Expertise fame, raised a few hackles over the weekend when he said marches really hadn’t achieved anything since the Civil Rights Movement.

News flash: You’re not John Lewis or MLK, and this isn’t Selma. And frankly, that was about the last time marches – led with dignity and respect because MLK demanded it of the protesters to showcase the inhumanity of the opponent – was about the last time marches did much. https://t.co/LWRYvLOdPh

— Tom Nichols (@RadioFreeTom) March 24, 2018

He’s not a fan of kids being coopted by adults for the adults’ pet causes, which evades the question of the agency of Parkland survivors and other young people to galvanize and lead a national movement. Social movement scholars, including me, took to Twitter to challenge Nichols’ assertion that marches and movements had not achieved much since the 1960s. Based on my work on transnational advocacy movements, I chided him in a Tweet thread:

Might want to study up on social movements a bit. My first book covers debt relief protests, AIDS protests, where marches along with other advocacy strategies worked. https://t.co/o7PRdu8Qcb https://t.co/lDpzKcj4Zn

— Josh Busby (@busbyj2) March 24, 2018

The 1999 G-8 summit in Cologne, Germany where the Jubilee 2000 campaign ringed the summit in their successful effort to get the IMF, World Bank, and major donors to write off developing country debt relief. I noted the 2000 International AIDS Conference held in Durban, South Africa, where the Treatment Action Campaign along with international supporters helped galvanize support for AIDS treatment access that culminated in the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria and helped usher in an era of low-cost generic AIDS drugs. Other examples came to mind, ACTUP and AIDS campaigners in the 1980s who challenged the medical establishment to fasttrack AIDS drugs in the developed word, the campaigns and marches to end apartheid, the Solidarity protest movement in Poland, among others.

Readers on Twitter asked what lessons does social movement theory have for the March for Our Lives march and wider gun safety movement. Here is my quick take from my work, which is more based on transnational advocacy movements rather than strictly the U.S. experience.

Social Movements Theory

In their classic formulation, McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald identify three different factors that facilitate or impede movement influence – cultural framings, political opportunities, and mobilizing structures. While I may do violence to their argument, my distillation would be along these lines:

- Frame resonance – Has the movement framed their argument to be culturally resonant?

- Political opportunity – Is there a favorable political opportunity structure to facilitate their influence now?

- Mobilizing structures – Does the movement possess enough people power and material influence to make decision-makers listen to them?

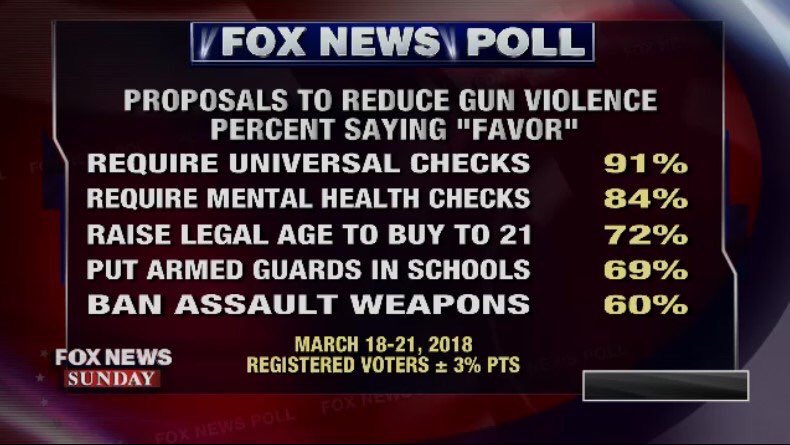

In terms of the frame, tying guns to the survival of kids seems like it has hit a nerve, generating support across the political aisle for action. It reminds me of Keck and Sikkink’s argument that campaigns tend to succeed when they can frame their issues with a short causal chain tied to bodily harm. That seems relatively easy to do in this case to tie guns to harm, and their demands such as better background checks appear to be widely popular (though some measures such as banning assault weapons are less popular than arming teachers). Tying gun violence to survival of kids meets Keck and Sikkink’s criteria for framing, and public opinion is largely supportive of efforts, though there is a reservoir of robust support, particularly in the South and among Republicans, for 2nd Amendment absolutism.

In terms of political opportunity structure, here it is a mixed bag. Certainly, there is more intense public interest in the issue than there has been in some time, but I’m not sure that on its own constitutes a favorable political opportunity structure. The Parkland crisis has wrought more elite division which has made the moment more ripe for progress (particularly at the state level in Florida), but when we look at Congress and Executive Branch, it’s not clear that structurally the situation has changed all that much or will change until the 2018 midterm election.

In terms of mobilizing structures, the recent marches all over the country clearly demonstrate the capacity of the gun safety movement to mobilize large numbers of people (see the Crowdcounting numbers from Jeremy Pressman, Erica Chenoweth, and Kanisha Bond that preliminarily exceed 2.4 million people).

Groups like Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense and Everytown for Gun Sense have developed organizationally capacity in recent years in the wake of the Sandy Hook shooting and other events. While the protest turnout this past weekend was impressive, we also have the countervailing political power of the NRA, its members, and financial resources that it has levied in the past to reward and punish political supporters and opponents. Perhaps the most important test of the gun safety movement’s mobilizational capacity is whether support this past weekend translates into into issue-specific voting pressure in the 2018 mid-term elections.

While young people are not the only people that came out in support of the march, they were prominent in the organization and as the face of the movement, but historically have not voted in high proportions compared to older voters.

Source: United States Elections Project

Other Social Movement Explanations: Framing, Gatekeepers, and Costly Moral Action

Classic social movements theory may be too indeterminate to offer clear predictions about the movement’s success. In my two books, I tried to offer more refined arguments to understand predict movement success. In my 2013 book on movements and markets with Ethan Kapstein, one of the factors that impedes movement success is the absence of a coherent ask. Unlike the Occupy movement, which was unable to translate citizen discount into a concrete legislative agenda, the gun safety movement seems to have a unified set of asks already.

In my 2010 book on moral movements and foreign policy, I made a slightly different argument. Movements are most likely to succeed when they frame their arguments to fit the cultural contexts where they are operating and make demands that are not costly for decision-makers. Where value fit and costs are both high sets up situations of costly moral action, which are tougher for movement success but not impossible. Whether or not states will embrace costly moral action depends on the number of veto players (which tend to be high in the US) and their preferences (heterogeneous preferences or strongly anti-movement preferences pose a high barrier to action).

It looks like the gun safety advocates have a case with some features of costly moral action. If we accept they have compelling frame, what about the costs? Here, we have to evaluate the movement’s key demands: universal background checks, mental health red flags, a ban on bump stocks, limits on domestic abusers buying guns, closing loopholes on background checks not completed within 3 days, banning high capacity magazines, and banning assault weapons.

It is not entirely straight forward to evaluate how costly these interventions are, since we are not really talking about a large outlay of money but the political costs of taking action. Some, like bump stocks bans, appear to be areas where President Trump may back unilateral action. Others, like background checks appear to be popular and could be relatively costly, except NRA absolutism may make it politically costly for some, mostly Republican, members of Congress to support them. Banning assault weapons, given the number in circulation, may be a heavier lift still.

If the case resembles one of costly moral action at least in part, that leaves us with an analysis of institutions. Who are the gatekeepers? While President Trump may be able to take some action unilaterally (and he remains a mercurial gatekeeper on this issue), most of the changes require legislative action. Here, we have the problem of key gatekeepers in the House and Senate, the Senator Majority leader and the Speaker of the House, being opposed to moving legislation forward. You also have the structural problem in the Senate of the filibuster, which Brian Beutler points out may leave gun safety legislation hostage to 41 senators.

Here again, the structure is against action because there are many gatekeepers in Congress and their preferences under current representation are hostile to action. This makes voter turnout this fall particularly important in changing the face of Congress (though the math is certainly unfavorable for Democrats in the Senate).

The challenge is whether or not gun safety will be a particularly important reason for people to vote in the fall. It’s not clear that there are that many single-issue voters who care that passionately about guns, but as Corrine McConnaughy argues, previous movements for women’s suffrage for example succeeded because the cause went beyond women’s suffrage:

One of the points of my book was that suffrage was won when the politics were actually *broader* than suffrage orgs only. Which was counterintuitive for original leadership.

— Corrine McConnaughy (@cmMcConnaughy) March 25, 2018

That certainly resonates with my understanding of the most classic case of costly moral action in the international arena, the fight against the slave trade. Kaufmann and Pape’s argument that Britain’s 60 year fight against the slave trade ultimately was more than a fight against slavery but for soul of the country, that was seen as corrupted internally by the stain of slavery. Gun safety campaigners could certainly learn from that and make common cause with others wanting good government. In their indictment of the NRA’s corrosive effects on U.S. politics, it seems like they already have.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments