This is a guest post by Michael Bosia, Associate Professor of Political Science at St. Michael’s College in Colchester, Vermont. You can find him on Twitter at @VTPoliticsProf.

In December 2001 – less than two months after the al-Qaeda attack on the World Trade Center and not even a month from the day US and UK forces invaded Afghanistan – I was with Act Up Paris as activists carried a banner emblazoned “AIDS: The Other War” to lead their annual World AIDS Day march. Behind the banner, marchers raised signs reminding that more people were dying from complications of HIV every day than were killed on 9/11 in lower Manhattan: “SIDA: 10,000 morts par jour” (AIDS: 10,000 Dead Each Day”). It was not the first time war as metaphor had colored the activist group’s rhetoric; in fact, their response to 9/11 is emblematic of how they combine as truth-telling both careful analysis and bodily provocation, often so unsettling, when confronting powerful elites and emboldened populists. While the portrait of Act Up in the United States has been presented in the 2012 documentary and 2016 book How to Survive a Plague, the stories of Act Up Paris and the challenges French activists faced are largely unknown to the English-speaking public, but that is corrected now that “120 Battements par Minute” (“BPM (Beats Per Minute)” in English) is available to stream in the U.S. This month named the César Best Picture and awarded the Grand Prix at Cannes last year, the fictionalized account depicts the early years of Act Up Paris.

Founded in 1989 after what some have called a lost decade in the French LGBT and anti-AIDS movements, Act Up faced both neoliberal economic change from the left and the rise of populism on the right in an early preview of today’s politics. In response, they were compelled by the death and disease they faced every day to develop new tactics and rhetoric, queering the powerful images and ideas inherited from the 1968 generation by inserting their bodies – so terrifying as transgressive and diseased – into the political discourse at the same time they acquired scientific expertise that blindsided the establishment.

Activist-director Robin Compillo has been lauded by veteran Act Up members for BPM’s exquisite evocation of the anger, pain, despair, and hope of those first years in the early 1990s, allowing us into what can only be described as a remarkably small group of friends, lovers, and comrades – not many more than a few hundred – who dedicated their lives and changed the world in which they lived. As Campillo’s film shows, this was not just a response to illness: activism reminds us that the body is the site of everything from lesions, blood, and semen to death, sex, intimacy, and joy, all made central to political struggle and discourse. Along with the standard tactics of political education and weapons like satire and drag, the body was as well a site where solidarity was crafted among those affected by the disease to sway a public and political leadership alternatingly hostile and indifferent. This is an important lesson for the resistance today as we seek to fuse the embodied marginalization of gender, race and sexuality with a sound analysis of the economic precarity wrought by crony capitalism and neoliberalism.

While the ravages of AIDS on the body have dominated award winning films before, even the central gay couple in Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia (1993), however loving, avoided the intimate physical contact that is central to the struggle against AIDS. The lovers and activists of BPM share an emotional, physical, sexual and political intimacy that connects their political struggle to their embodied selves and their search for knowledge. In a startling contrast, the final scene of the dying main character in the US film dissolves into home movies of his childhood, while one pivotal moment in BPM pans out from the coffin of a fallen activist to a giant political funeral march through the center of Paris, followed by the use of his ashes as part of an action targeting a pharmaceutical company.

Act Up Paris was organized in the wake of a series of unresponsive governments. Though the Socialists elected in 1981 removed the remaining vestiges of the criminalization of homosexuality soon after taking office, the government’s focus on economic reform and globalization in the era of Reagan and Thatcher, coupled with the kinds of visceral homophobia that ranged from the opprobrium of the governing parties to the virulent hostility of populists, resulted in a number of stunning failures to intercede against AIDS when early action could make a difference. Political and medical leaders somehow felt France was safe, as they assumed AIDS was an American disease, and that because of this, France and French gay men were largely free of risk unless they made the mistake of cavorting in the US. With AIDS often called a “Cancer Gay New Yorkaise,” the newspaper Le Matin in 1983 published an early story about the disease under the headline “AIDS Made In America” (in English).

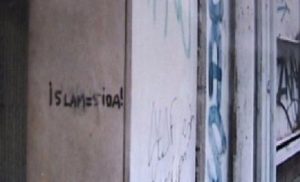

Chief among the extremists was the leader of the National Front, Jean-Marie Le Pen, who said in 1984 that “homosexuality, if it is allowed to develop, represents the end of civilization,” warning in a television interview that “immigrants will move in with you, eat your soup and sleep with your wife, your daughter, and your son.” AIDS provided just the right glue to bind together those sexual and foreign bodies he despised, with the emerging story of its origins in Africa and US. In 1986, without a standard term in use to describe those living with HIV/AIDS, Le Pen coined his own: Sidaïque. The word combined the acronym for AIDS in French (SIDA) and Judaïque, used to describe the Jewish faith or culture that Le Pen considered as “oriental” as Arab culture. In 1997, I found the extremist party’s message reduced to a simple slogan written in graffiti on a wall in the French capital: “Islam=SIDA.”

Act Up Paris responded by claiming its legitimacy as a French movement, in terms that resonate broadly in French politics but that also bridged the alternative movements that began in 1968 and continued to build through the 1970s and 80s. They did this in two ways. First is the story of a young hemophiliac with HIV and his mother, victims of the government’s decision to hold off on US-developed blood purification technology and instead to supply French blood products infected with HIV for the treatment of hemophilia. Turning to Act Up when they could find no other support to channel their anger and fear, and featured by Campillo in the film as Marco and Hélène, their story is central to the early years of the movement by providing Act Up the ability to offer a daily account of outrage against the highest government officials. With administrators on trial in 1992 over the distribution of contaminated blood, Act Up convinced a largely hostile public that the spread of HIV resulted from neoliberal economic policies that prioritized profit and the position of French industry in a globalizing economy, establishing that the government failures at the heart of the epidemic were written on the bodies of hemophiliacs in the same way they were written on the bodies of gay men. Seizing their own credentials as more credible sources and advocates for the public interest than Socialist government officials or some of the experts in the medical establishment, they demonstrated that gay men, even as they faced ostracism and death, were more concerned about mothers and children than the populists pretended to be.

Second, Act Up Paris launched a vigorous operation to build networks among immigrant populations, an intersectional approach credited in part to Act Up theorist Philippe Mangeot who co-wrote the film with Campillo. Ultimately embedding political interventions in counseling services for HIV positive immigrants, it was designed as a reflexive political dialogue so that action would meet the needs of the populations affected. This is how Act Up became intimately knowledgeable about and involved in immigrant and anti-racism politics, with activists often rushing to the airport to form a bodily blockade in front of authorities executing a deportation order against an undocumented immigrant living with HIV in France. It was over the expulsion of one such immigrant that an Act Up president disrupted a 1996 national AIDS telethon during prime time to confront a government minister, crying in frustration, “C’est quoi, ce pays du merde?” (“What is this f**king country?”).

Though Campillo situates his film nearly 10 years before the events of 2001 with which I began, the narratives of love and anger it tells, and the details of scientific research, reflexive strategies, and embodied rhetoric it reveals, are the same ones illustrated in the Act Up Paris march on that cold World AIDS Day. AIDS activists drew from their personal experiences with death and life to tell stories of marginalization in vividly embodied terms, establishing parallels between the debates over neoliberal economic policies and populist responses to migration with the physical experiences of people with HIV. Even dressed in drag as cheerleaders for one gay pride march, they used their physical selves as part of a rhetorical arsenal that confronted neglect and loathing with the joyousness of love and solidarity. Never shy and always provocatively confrontational, their response to the events of 9/11 and the war in Afghanistan paralleled their assault on the medical, research, and political establishment throughout the 1990s.

As instruction in embodied solidarity, BPM reminds us how human experience situates marginalized, transgressive and diseased bodies at the forefront of politics, against the dominance of a privileged group of white, straight, men – both elite and populist – who distort the public good, silence the marginalized, and redefine economic policy on terms written by the privileged. It is a lesson many have learned – from the organizers of #BlackLivesMatter and the Women’s March to the spontaneous demonstrators who occupied airports in response to the so-called “Muslim ban” and others coming forward as part of #MeToo.

Jeremy Youde, Ph.D., joined the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD) as dean in July 2019. From 2016 to 2019, Youde was an associate professor in the Department of International Relations in the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs in the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia. During his tenure there, he served as deputy director (Education) for the Coral Bell School, interim head of the Department of International Relations, and acting associate Dean (Education) for the College of Asia and the Pacific. Before going to Australia, Youde was a member of the Department of Political Science at UMD from 2008 to 2016. He earned tenure at UMD in 2012 and served as department head for three and a half years. He previously held appointments at Grinnell College and San Diego State University.

a pity this film who gives good recipes from Act Up Paris to young generations is not fare with the minorities inside Act Up Paris. The part of women -lesbians was importants- is eradicated. Act Up Paris was the first aid association in paris to open a trans commission, using Walter Bockting works. The film is not in the chronology this commission was created after the death of Clews Valleys. Here you have one trans -a bit ridiculous- telling she is not feeling well and they should work with HIV and Hormones. Its a bit painfull to explain you we worked on the subject because in another association three girls had died with those HIV-Hormones problems. I am not going to shout homonationalism, yet it deceiving. I hop success to the film. One important figure is forgotten, Pierre Berger .