I had the good fortune during my brief appearance at ISA to take part in a roundtable on “Jacksonianism” in U.S. foreign policy. Organized by Jon Caverley, the roundtable sought to assess whether the Trump presidency represents a new equilibrium in which a Jacksonian foreign policy orientation has if not pride of place a more vaunted position than it once had.

Excited to roundtable (is that a verb, yet?) with @jcaverley Lene Hansen @busbyj2 @MeganhMackenzie @swatipash about Trump, IR, and the new Jacksonian moment in world politics — at 1:45 PM today at #ISA2018 (Hilton Continental 4)

— Josh Kertzer (@jkertzer) April 5, 2018

“Jacksonian” is the term Walter Russell Mead coined in his 2002 book Special Providence to reflect a foreign policy tradition that was inward looking, shunned international engagement, but prepared to aggressively defend US national security if the country was threatened. Jacksonians had largely been a rump faction in American political life, periodically emerging as a more potent force during occasional bouts of populist sentiment.

My remarks reflect my sense of the significance of the Trump phenomenon for foreign policy. I’m currently reading How Democracies Die, and I am not sure what worries me more, President Trump’s aggressive gamble to coerce Kim Jong Un to denuclearize or Trump’s steady effort to weaken the rule of law and democratic institutions here at home.

I’m delighted to be part of this roundtable. I wanted to reflect on the Chicago Council on Global Affairs polling data that shows relatively robust support for international trade, international organizations, and more open immigration and how to square that with President Trump’s narrow electoral college victory and relate it to this panel’s theme on whether the Jacksonian tradition is ascendant if not dominant. My remarks are informed by a chapter with Jon Monten that appeared in a recent edited volume Chaos in the Liberal Order.

.

By Jacksonian, I mean an America-first nationalism, undergirded by trade protectionism, and rejection of international institutions and alliances as a means of pursuing American interests overseas. It is an inward focused foreign policy orientation but is prepared to muscularly and unilaterally use force if the country is threatened. Unlike neoconservatives who are committed to remaking other states in America’s self-image as liberal democracies, Jacksonians are conservative nationalists who have no aspirations for extending the liberal project beyond America. Where Paul Wolfowitz is a neoconservative, John Bolton is not and more representative of the Jacksonian tradition.

I want to begin by asking if Americans at this moment are Jacksonian.

Getting it Wrong: Elites Don’t Know What Public Attitudes Are

The Chicago Council, where I’m a nonresident fellow, has done several polls in the lead up to the 2016 and afterwards which show the American public retains relatively robust support for international trade, traditional alliances like NATO, and paths to citizenship for migrants. Moreover, in 2016, when more than 400 foreign policy elites were asked what they thought public attitudes were towards the United States taking an active role in world affairs, elites roughly said half the public was in favor. The actual percentage that year was 64%.

When elites were asked what percentage of the public would say globalization was mostly good for the United States, they said 29% of the public would make that claim. The true figure that year was 65% of the public said globalization was mostly good for the United States.

When elites were asked whether they thought the public was more supportive of illegal immigrants being forced to leave the country or could stay, elites said 37% of the public would favor migrants leaving. The actual figure was 28%. Republican elites were even more off target in their assessment of public attitudes suggesting that 60% of the public favored deportation.

You might think this is an artifact of question wording or a one off poll, but when CCGA surveyed the public again in 2017, they reached similar findings. 63% wanted to maintain an active role in the world. 72% said international trade was good for the US economy. 65% supported a path to citizenship for immigrants either with or without conditions?

But Trump Won!

How can we reconcile these opinion poll results with Donald Trump’s victory? Every day we are witness to fitful efforts to put into practice that Jacksonian vision, whether it be imposition of tariffs, diatribes against NATO allies for inadequate defense spending, threats of war against Iran and North Korea, and efforts to wall America off from new immigrants and kick out those who are here. If these views are not popular, does that suggest the Jacksonian impulse is likely to be a short-lived spasm, an aberration?

First, it is important to note that President Trump lost the electoral college in an election in which a significant chunk of the electorate did not turn out. Only about 60% of eligible voters voted. So when we think about whether Jacksonianism is ascendant, we need to be clear that those who voted from Trump (which included Jacksonians and others) represented about 27% percent of eligible voters.

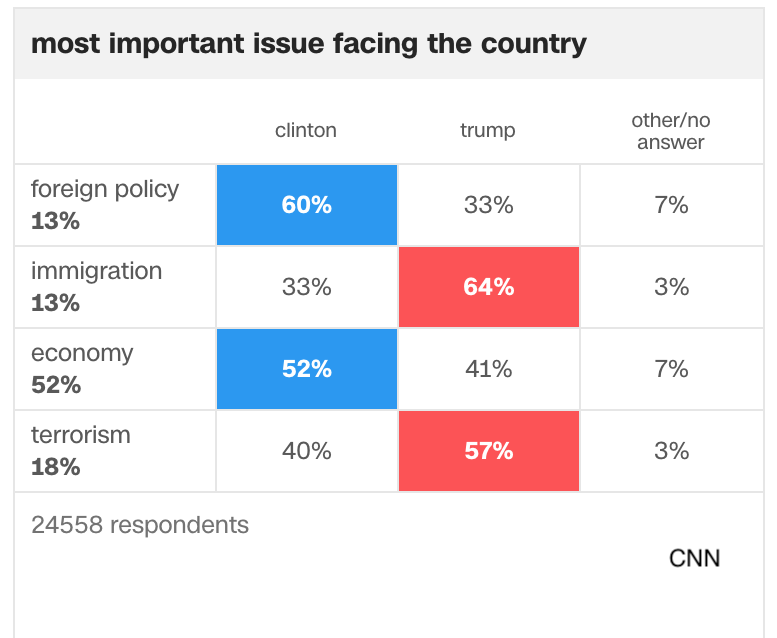

Second, it’s a little unclear if foreign policy mattered in the 2016 election. Most elections it doesn’t. 2016 was a strange year. Roughly 28% said either foreign policy or terrorism was their top issue, which is pretty high for a presidential election. However, 60% of those who said foreign policy was their top issue voted for Hillary (13% of the total). But 57% of those who said terrorism was their top issue voted for Trump (18% of the total). So, even if foreign policy concerns mattered in the 2016 election, the effects seemed to be offsetting.

Funhouse Mirrors: Elites and Public Opinion

If foreign affairs are not salient for most voters, then public opinion may be less relevant to explaining the importance or durability of Jacksonian foreign policy approaches. Elite dynamics may matter more if we think the public is by and large disconnected from foreign policy, save for occasional moments of great crisis.

That being said, some intermestic issues like trade and immigration were salient in the last electoral cycle, but that means we have to explain the disconnect between Trump’s performance and public attitudes.

Public opinion polls rarely tell us about the relative salience of issues. Here, elites generally are more attuned to the loudest voices who care passionately about particular issues. This would help explain why elites believe the public to be less internationalist than they are and to be more hostile to trade and immigration than they are. With very few districts competitive in recent elections, we increasingly saw Republican elites attuned to their primary voters who hold extreme views on these questions.

Elites are not only responsive to party extremes, but they can also remake the foreign policy attitudes of the rest of the party under certain circumstances by cuing their voters, as Guisinger and Saunders show persuasively. Thus, even as we see overall broad support for globalization and trade agreements among the public, we have seen Republicans and Democrats switch places in terms of their support for trade agreements as their leaders did. So, Democrats after being hostile to trade agreements in the Bush years became more supportive of free trade when Obama championed them w Republicans becoming less supportive in reaction to Obama. Partisanship is a hell of a drug.

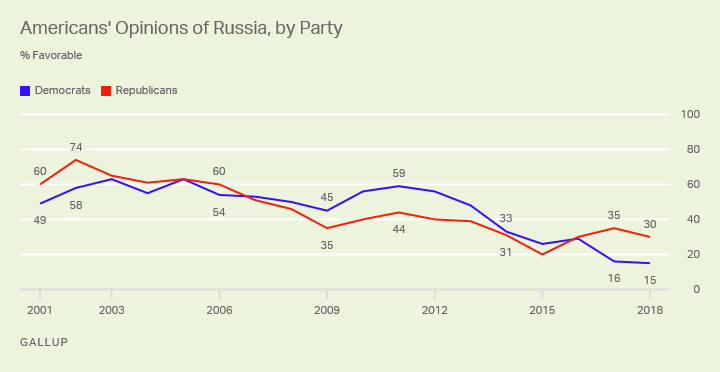

We also see Republicans, traditionally stalwart supporters of free trade, increasingly becoming more hostile to free trade in response to Trump’s messaging. That may also reflect a partisan re-sorting or realignment as white working class voters drift in to the Republican column in response to Trump’s messaging and stay there. We see similar elite cue effects on Republicans’ increasing support for Putin and Russia in response to Trump’s warm comments about Putin and Russia.

Is this Jacksonian Moment Durable?

I want to come back to the question of the durability of this Jacksonian moment. Some like Ron Krebs have argued that Trumpism is unlikely to leave as lasting an effect because the foreign policy establishment was by and large resistant and hostile to this view.

Presidents need appointees to be able to carry out their vision. Jacksonians were in short supply in the cohort of appointees with foreign policy in their portfolio at the beginning of the Trump administration. We had more establishment figures in key positions of power, namely Mattis, Tillerson, Cohn, and, after Flynn’s departure, McMaster. The establishment antibodies were thought to be strong. The few champions of Jacksonianism like Stephen Miller were pretty junior or peripheral such as Navarro with other figures like Pompeo and Kelly somewhat ambiguous figures.

However, as we have seen, Trump has increasingly been happy to jettison the establishment in favor of more arguably Jacksonian individuals. So, Tillerson is out in favor of Pompeo, McMaster is out in favor of Bolton, Cohn is out in favor of Kudlow, and Navarro and Miller’s fortunes are rising.

What’s more, the administration by attrition is losing establishment types by refusing to fill positions across the government. And, with many Never Trumpers blackballed for signing anti-Trump letters, it is hard to replace them. Tillerson’s ill-considered reorganization effort also drove diplomats and professionals out of the State Department. Moreover, the direct attacks by the President on the legitimacy and indepedence of the CIA and FBI will yield a similar result that extends well beyond James Comey and Andrew McCabe at the FBI.

The net result is an executive branch bureaucracy that is hollowed out and less able to execute generally but also perhaps more pliable to Trumpist policies, particularly when it comes to issue like trade and immigration. As long as Mattis is Secretary of Defense, that impulse may be thwarted in defense arena.

It remains an open question whether there will be Congressional counterparts to Trumpism. On some issues, like Iran and North Korea, there is a hawkishness that resonates with Republicans beyond the Trumpist core. However, on other issues like trade, alliances, even immigration, the party is more divided.

The real question is whether Republican members of Congress believe Trumpism is a winning approach. While this might be mostly about domestic politics, electoral success by Trump acolytes on domestic policy grounds would likely buoy Trumpist foreign policy by creating a more homogenous party on both domestic and foreign policy.

As it now looks, Trumpism appears to be headed for a sound electoral defeat, at least in the House, which raises questions about how elites, particularly Republicans, will respond, will they be emboldened to question Trump on foreign policy or be as a supine as they have largely been up to now.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

It is hard to imagine a more dishonest, wrong-headed essay than this one. If we have seen anything during his administration it is the wanton disregard of the plain language of statute law by numerous left-wing judges, especially in the area of immigration. Compared to the rampant disregard of law and Constitution by the Obama regime, Obama’s open collusion with the Iranians, and Obama’s autocratic rule by executive order, and Obama’s numerous war crimes, including the murder of at least one million civilians in the Middle East, the Trump administration is a breath of fresh air and a return to the rule of law.

I can scarcly imagine a more emotionally charged, baseless, hypocritcal, comparitive comment. In truth, I’m a fan of neither regime, but both have relied on EOs to bypass congress when they became inconvenient, neither have a strict constructionist view on constitutional law, and both have had issues (albeit, starkly different ones) with interacting with the International community.

Trump is a breath of “fresh air” in the same way flatulence is a change of pace from rotting produce. The only good he’s done, IMO, is to distrub the deep-state, but what he replaces them with is seldom effective (there are some noteable exceptions).