The following is a guest post by Carla Martinez Machain, Michael Allen, Michael E. Flynn, and Andrew Stravers.

One week ago, National Security Adviser John Bolton appeared at a White House briefing holding a note pad with the phrase “5,000 troops to Colombia” written on it. This occurred in the context of rising tensions between the U.S. and the Maduro government in Venezuela after the U.S. recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the legitimate leader of Venezuela. Since then, there has been much speculation about how likely a deployment is to happen and what it means for the possibility of a US intervention in Venezuela. Of note, Congress currently limits the U.S. presence in Colombia to 800 military personnel (and 600 contractors).

A potential deployment of this size has serious implications for US relations with Colombia, Venezuela, and the Latin American region as a whole. In particular, it can affect how populations perceive the U.S. government and its military. What does current research on the effects of U.S. deployments tell us about how such a move would affect public opinion of the U.S. in Latin America?

U.S. Military Deployments in Latin America

This past summer, our research team traveled to Central and South America to interview local government officials, U.S. embassy officials, and local members of civil society on how a U.S. military presence affects views of the U.S. in host countries. During these interviews, locals repeatedly reported a perception that the U.S. had plans to deploy troops to friendly countries in the region in order to launch an intervention in Venezuela. For example, interview subjects at the U.S. embassy in Panama told us that whenever U.S. troops deploy to Panama for training exercises, there are reports in the local press about Americans going to Panama to establish a base to spy on Venezuela and to prepare for an invasion. Another subject, a Panamanian journalist, confirmed this view.

Some embassy personnel noted that this was not necessarily a bad thing, as it could potentially place pressure on Venezuela to democratize. Given that this view was already prevalent in diplomatic circles last year, it is even harder to believe that Bolton’s “mistake” was an accident. Such a moment could serve as another (less subtle) form of pressure on the Maduro regime.

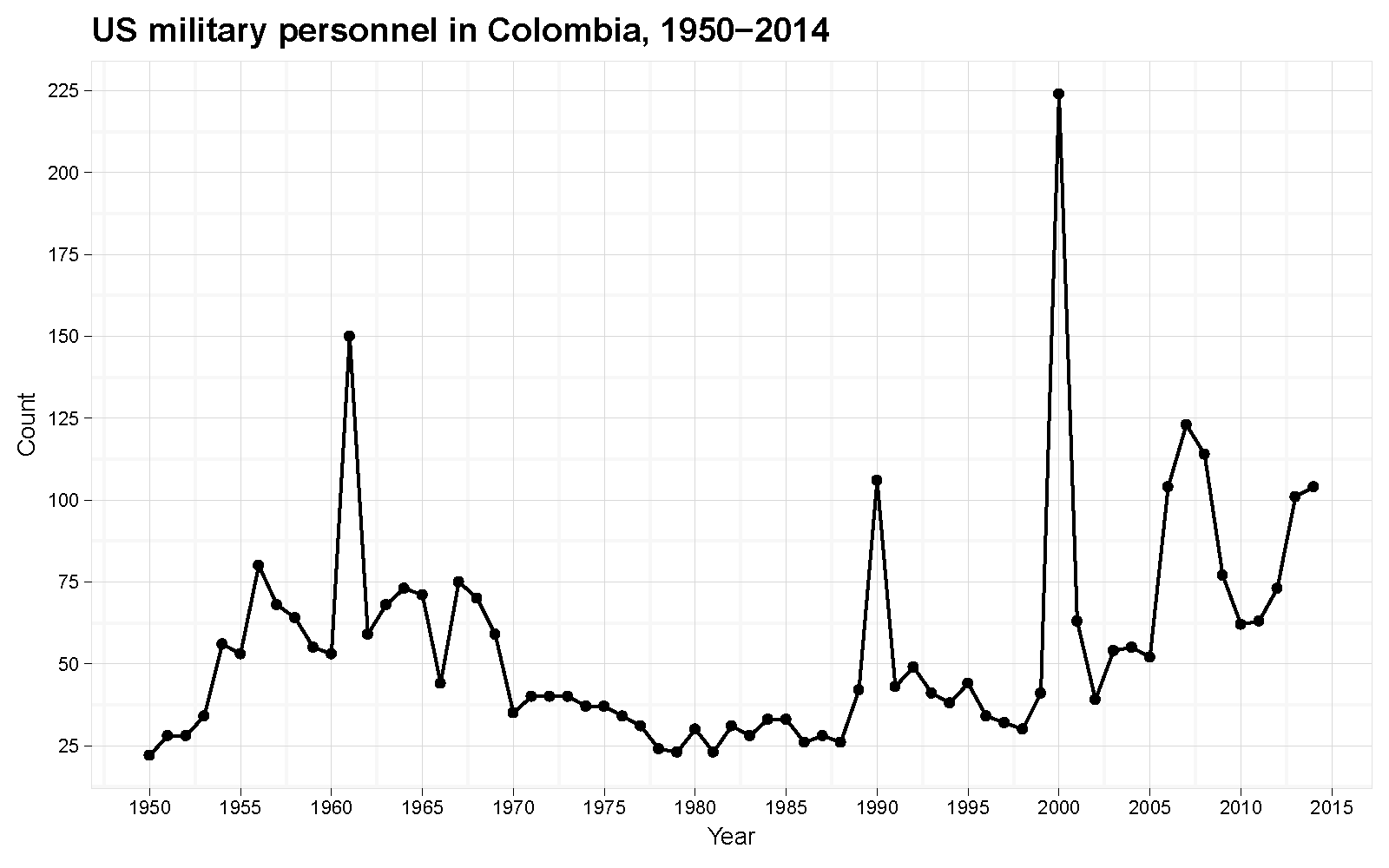

As shown by the figure above, since the 1990s Colombia has had a history of hosting US troop deployments, many of them as part of Plan Colombia. At the same time, these numbers never approximated the size of the deployment that Bolton may have been considering. At the peak of the U.S. military presence, in the year 2000, there were 225 active duty US troops deployed to Colombia (this number does not include military contractors or other DOD personnel who have been present in support of the troops). As of the most recent reports from the U.S. Department of Defense (September 2018), there are currently 64 active duty US military personnel deployed to Colombia. A 5,000 deployment of military personnel would be a substantial increase over historical numbers.

Implications for Perceptions of the US in the Region

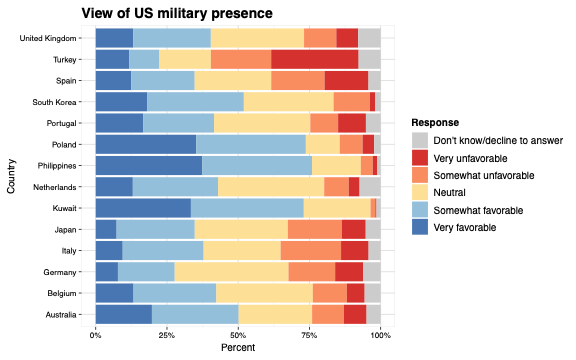

Latin America is a region that traditionally has had positive perceptions of the U.S. At the same time, the United States’ previous military interventions in the region as part of its drug wars and counterinsurgency operations have also bred suspicion about U.S. interventionism. As part of our research project, we conducted a 14,000 person survey across 14 countries that have had large peacetime U.S. troop deployments. Our results show that all else being equal, having direct contact with a member of the U.S. military actually leads to more positive perceptions of the U.S. military and of the American people as a whole. This implies that a military presence in and of itself will not necessarily lead to negative views on the U.S. Of course, the context of the deployment would matter as well.

A large U.S. deployment to Colombia could easily play into the hands of many leftist groups throughout the region and perpetuate ideas that U.S. humanitarian assistance and military exercises (such as medical care provided in November 2018 by the US navy hospital ship USNS Comfort to Venezuelan refugees in Colombia) have ulterior motives. Additionally, criminal behavior by military personnel can become national news stories and feed anti-US sentiment. Our past research shows that humanitarian assistance provided by the U.S. military is correlated with greater trust in the U.S. government and military . If leftist groups are indeed able to link these deployments with interventionism, that trust could be eroded.

Some may argue that a greater U.S. military presence in the region could prevent future human rights violations by Latin American government. After all, even Colombia, often held up by the U.S. as a counterinsurgency success story, has experienced human rights violations in heavy-handed counterinsurgency operations by the military. Existing work has shown that in some cases, U.S. troop deployments are correlated with greater respect for human rights. Yet, this is true only in areas that are of low security salience for the United States. Given the high security interest that the U.S. has in Colombia, both because of counterdrug operations and because of its proximity to Venezuela’s leftist government, a large deployment would be unlikely to lead to improved respect for human rights in the region.

Recent talk from Bolton about the benefits of opening Venezuelan oil to U.S. companies did little to contradict narratives of renewed U.S. interventionism in Latin America, and signaling U.S. intentions to send more military forces to the region also makes the suspicion seem more plausible. While pressuring the Maduro regime through these signals may have the intended effect in Venezuela, it would be wise for the Trump administration to take these more region-wide political dynamics into account, if its goal is to diminish Maduro-style forces throughout the whole of Central and South America.

This material is based upon work supported by, or in part by, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the U.S. Army Research Office under grant number W911NF-18-1-0087.

Amanda Murdie is Professor & Dean Rusk Scholar of International Relations in the Department of International Affairs in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia. She is the author of Help or Harm: The Human Security Effects of International NGOs (Stanford, 2014). Her main research interests include non-state actors, and human rights and human security.

When not blogging, Amanda enjoys hanging out with her two pre-teen daughters (as long as she can keep them away from their cell phones) and her fabulous significant other.

0 Comments