This post, part of the Bridging the Gap channel at the Duck, comes from Michelle Jurkovich, an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts Boston. She is a 2019-2020 Public Engagement Fellow with Bridging the Gap and an alumna of BTG’s International Policy Summer Institute. During 2017-2018, she was an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science and Technology fellow working in the Office of Food for Peace at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

We talk about norms a great deal in international relations (IR) scholarship — but what are the edges of this crucial concept? In a recent article in International Studies Review (“What isn’t a norm?” – ungated until September 21), I argue that in using the term in increasingly flexible ways, scholars have blurred important differences between norms, supererogatory standards, moral principles, and formal law.

Understanding differences among these concepts enables us to better analyze the social and normative environment in which important international actors are working. Enhancing the conceptual toolkit we use to make sense of the social world to encompass more than just the “norm” also helps to highlight potential areas of conceptual stretching, which, as Sartori (1970) warned, may lead to false equivalence.

The article is a conceptual piece, but it was driven by a desire to understand some important real world challenges. Why is it so difficult to effectively use shaming strategies around some global problems (like hunger or homelessness) that everyone agrees are morally repugnant? While many human rights are codified in law, are all human rights codified in law also governed by norms? And if they aren’t, how can we make sense of the social environment around them? (My forthcoming book Feeding the Hungry: Blame Diffusion in International Anti-Hunger Advocacy with Cornell University Press tackles these issues with greater depth.)

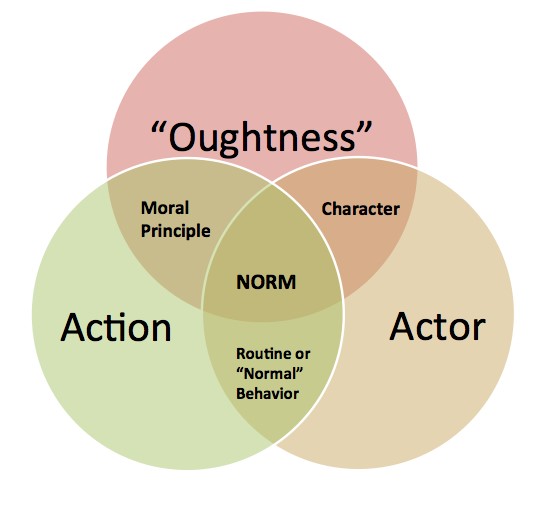

In my article, I propose the following way of conceptualizing the norm and its conceptual edges (see figure above), based on the definitions of a “norm” provided in both Finnemore and Sikkink (1998:891) and Jepperson, Wendt, and Katzenstein (1996:54). Based on these definitions, norms consist of three essential component parts: (1) a sense of “oughtness,” (2) a defined actor, and (3) a specific behavior or action expected of that actor. A norm must also be collectively shared within a particular society (or else it would be an individual’s private belief) and its component parts need to be specific enough that it is possible for a violator to be identified. Put plainly, norms require a social agreement about who should do what.

The challenge for many issue areas — and economic and social rights in particular — is that reaching a socially shared understanding of “who should do what?” is especially difficult. As an example, there may be widespread agreement in a given community that hunger is morally bad, or that it is a tragedy that children go hungry in the modern age, but without the benefit of an actor from whom a behavior is expected, this remains a moral principle, not a norm. It should then be less surprising to us when the strategies (like shaming) available to activists in issue areas with the benefit of norms fail to be effective here. Despite the existence of international law ascribing responsibility to states for ensuring the right to food for their people, this does not mean there is a norm that “good states ought to ensure their people have enough food to eat.” Laws and norms are not the same thing and they do not always walk hand-in-hand.

As our field hones new methods for aggregating an impressive amount of data on social communities it is equally important that we spend time carefully considering the concepts and categories into which we are sorting this new information.

Bridging the Gap promotes scholarly contributions to public debate and decision making on global challenges and U.S. foreign policy. BtG equips professors and doctoral students with the skills they need to produce influential policy-relevant research and theoretically grounded policy work. They also spearhead cutting-edge research on problems of concrete importance to governments, think tanks, international institutions, non-governmental organizations, and global firms. Within the academy, BtG is driving changes in university culture and processes designed to incentivize public and policy engagement.

0 Comments