This is a guest post by Summer Marion, a Pre-Doctoral Fellow at Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and Northeastern University, where she is a PhD candidate in Political Science. Her research examines international cooperation and crisis politics, with a specific focus on philanthrocapitalism in global health emergencies.

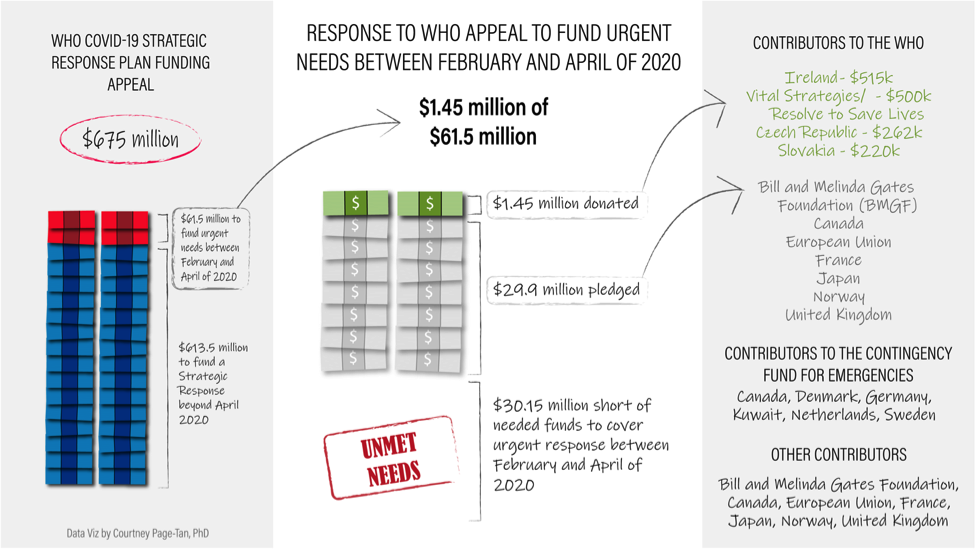

On February 5, World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus asked the international community for $675 million to fund a global response plan for the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, including $61.5 million to cover urgent needs between February and April of 2020. Funding in the early stages of an outbreak can mean the difference between virus containment and further spread.

As of February 28, closing out the first month of the three-month plan, more than 2,800 people have lost their lives and WHO has received only $1.45 million. This constitutes just 2.4 percent of the $61.5 million urgent appeal. It remains unclear how much has been pledged toward the total $675 million ask. While WHO reports donors have pledged an additional $29.9 million toward the urgent response, promises of future cash do little good in fast-moving crises.

As the virus continues to spread, with cases spiking in South Korea, Iran, and Italy last week, the international community’s financial response is emblematic of problems that run much deeper.

This post examines funding mechanisms in the context of this latest Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). My primary takeaway is that influx of cash during crises is a short-term necessity that distracts from much-needed long-term investment in global health infrastructure.

This piece builds on a six-part series of posts by Josh Busby covering background on this new virus, politics of declaring a PHEIC, international travel restrictions, China’s domestic response, next steps for this response and future outbreaks, and steps for individual and community preparedness.

The cost of responding to an outbreak

The cost of outbreak response varies based on scientific factors—like disease transmissibility and lethality—and political dynamics. Disease monitoring and surveillance, information-sharing, vaccine research and development, and basic health care provision including hospitals and protective equipment are politically influenced processes.

Early action is critical to mitigating long-term consequences, but so is stable funding during non-crisis periods. Given all that remains unknown about the virus, it is difficult to assess how much money the global response will ultimately require. The WHO’s $675 million appeal for COVID-19 estimates both short and long-term needs upfront, appearing to come with a steeper price tag than early appeals for past global health emergencies.

Some have drawn comparisons between this ask and the organization’s much lower initial 2014 appeal for $71 million at the onset of the West Africa Ebola outbreak. Yet the Ebola appeal is in fact similar to the WHO’s $61.5 million estimate for urgent needs over the first three months of the COVID-19 response. It was conceived to fund a regional plan to contain the virus—and only the beginning of what Lawrence Gostin and Eric Friedman described as a “succession of rising cost estimates.” It was announced before a PHEIC had been declared, a delay for which the WHO was subjected to sharp criticism.

Though the COVID-19 PHEIC declaration occurred more rapidly, many experts maintain WHO should have acted sooner. The COVID-19 appeal came at a time when the organization’s official strategy was still containment (rhetoric which persists, even as CDC officials warn containment has failed), yet it was made on the heels of the January 30 PHEIC declaration.

Current evidence indicates COVID-19 is more transmissible and therefore spreading more quickly, but less deadly than SARS or MERS, other members of the coronavirus family. Most cases appear mild. Because the same virus may behave differently in different contexts transmissibility estimates could change rapidly as the virus spreads.

What could states have done to better prepare? The 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR) reflect learnings from the SARS outbreak, mandating information-sharing and disease monitoring and surveillance during non-crisis periods, yet include no funding mechanism.

At the onset of the 2014-2016 Ebola response, fewer than one third of member states were compliant with IHR guidelines. The status of IHR compliance today remains similarly low. Many countries lack the resources; others can afford to comply, but lack the political will to lead coordination efforts. Effectively addressing this outbreak costs more in the short-term because states have not invested in necessary measures over the long-term.

Outbreak funding mechanisms

Who is giving to the global response, and how? The Czech Republic, Ireland and Slovakia remain the only member states to have given outright in response to the WHO appeal. Despite the dearth of liquid cash, however, state and non-state donors alike have pledged money toward the appeal as well as other funding mechanisms.

On February 7, amidst rising tensions the between the US and China over travel restrictions and information-sharing, the US committed up to $100 million in aid to China and other countries affected by the outbreak. A State Department press briefing indicated some of these funds would support WHO efforts.

The EU pledged over $250 million (€232 million). According to a European Commission press release, $124 million (€114 million) of that goes toward the WHO response plan. The rest contributes to research and repatriation for EU citizens in Wuhan, China. Some of this commitment is allocated to the $29.9 million in pledged dollars WHO reports for the urgent response phase, though it is unclear how much. The graphic below summarizes the current response to the WHO appeal, alongside other commitments:

Pandemic bonds, an investment option established through the World Bank Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF), are another option for financing outbreak response—one which has yet to pay out for COVID-19. The bonds provide an annual return between eight and 13 percent; in turn, investors risk financial loss when a payout is triggered. Since the mechanism’s inception, payments in fees and returns to investors far exceed outbreak response payouts.

As Bangin Brin and Clare Wenham argue, most health experts consider this option deeply flawed in that it prioritizes private interests over public health needs: the benchmark for a payout is complicated and difficult to meet. Devi Sridhar warns if a payout is triggered for COVID-19, funds would arrive too late—not until March 23—and entail only $196 million for 76 affected countries.

A group of US. think tanks proposed a revised World Bank funding mechanism to help low-income countries, yet many experts assert the money should instead go directly to WHO.

Though Bill Gates has gone on the record stating that private giving cannot take the place of large state donors, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) responded with a $100 million envelope, including a $10 million commitment made in January of this year. Independent foundation funding has grown to account for up to one fifth of development assistance for health in recent years. Yet before the 2014-2016 Ebola response, major gifts from foundations during crises were rare, most preferring to give to longer-term goals.

BMGF funds cover accelerated detection, support for at-risk populations, and vaccine research, including funding for the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness (CEPI), a vaccine development initiative BMGF co-founded with the Wellcome Trust and the governments of Norway and India. Wellcome Trust committed just shy of $13 million (£10 million), including the launch of an Epidemic Preparedness Funding call in partnership with the UK Department for International Development (DFID).

When it comes to vaccine development, National Institute of Health expert Anthony Fauci claims no major pharmaceutical company has stepped up to back the process. Though this is the third coronavirus outbreak over the past two decades to merit a global response, research funding ebbs and flows around crises. Few researchers remain dedicated to coronavirus between outbreaks. In addition to covering basic health care needs, sustained research funding for persistent global health challenges will better position the world to address the next outbreak.

How money matters

Money can cover urgent needs, but cash alone cannot facilitate the political will required to strengthen health systems over the long-term, protecting against future outbreaks and higher costs down the line. As experts acknowledge this outbreak will have widespread reach, state governments are preparing domestic response plans.

Some may bolster global efforts—US Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer’s $8.5 billion request to Congress, for example, includes $1 billion in emergency development assistance. PHEIC declarations often spur donors to act—a large commitment from just one state could motivate others.

Yet in an era of faltering multilateralism and absent US leadership, no donor has stepped up. Heeding the WHO call to action earlier would likely have saved lives, as well as money. Beyond that, this response would come at a much lower cost had states invested in global IHR compliance over the years since SARS.

This outbreak, like others before it, lays bare a contrast plaguing global health emergencies: the securitized hype that can drive donations and media attention also fuels responses rooted in fear—just when cooperation is most needed.

This pattern of distrust plays out in aid flows, harkening to Sara Davies’ dichotomy of cooperative versus national interest-driven approaches to health emergencies. Reactive border closures and economic protectionism perpetuate nationalist thinking about a transnational challenge. Cooperative mechanisms work only when we invest in them—for the long-term as well as the short.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks