This is a guest post from Yongjin Choi, a PhD Candidate in the Department of Public Administration at Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, University at Albany. His research focusses on evidence-based policy, Medicaid, and citizen participation. Before entering the doctoral program, he worked as a researcher at the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST) for several years. He is currently working as a research assistant at the Center for Technology in Government (CTG). Follow him at @TheYongjinChoi

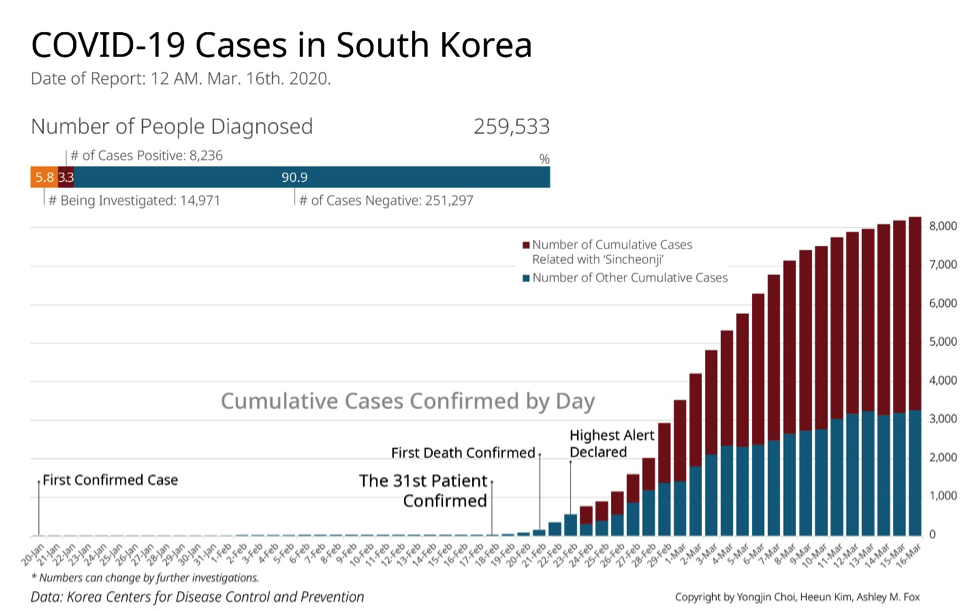

While the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea, which as of March 16th reached 8,236 confirmed cases, appears to have turned the corner on new infections, it has also served to highlight ongoing socio-political tensions in the country between the government and religious groups that have grown increasingly politically influential.

The coronavirus began to spread nationwide in February, following community spread from a large-scale service of a doomsday “cult,” the Sincheonji church of Jesus, in Daegu (now the most affected region of the country), drawing attention to the risk posed by large, in-person religious services. In spite of the churches’ known role in the continued spread of the virus, the central government has been reluctant to issue anything more than voluntary guidelines urging churches, in particular, Christian megachurches, to move their services online and stop meeting in person demonstrating the growing political clout of these religious groups in Korean society. Below I review the Christian churches’ role in the spread of COVID-19 in Korea, the government’s response and provide some context to understand the growing political influence of megachurches in Korean society.

Korea’s COVID-19 outbreak has largely been blamed on a religious cult

The first known case of community transmission in Korea, discovered on February 18th, spread from the 31st confirmed case a member of the Shincheonji Church of Jesus, a megachurch that holds that it is the only real church that upholds the biblical truth, but not before she had come in contact with over 1,000 churchgoers who met at Daegu’s Shincheonji church for prayer services. According to the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), this event has triggered nearly half of South Korea’s COVID-19 infections. The number of confirmed cases in South Korea spiked exponentially soon after the prayer service as confirmed by the prompt follow-up contact tracing of the KCDC.

The church members may have initially been exposed after about 200 members of the Shincheonji Church met in Wuhan in January, which may be at least partially responsible for having brought the virus to Daegu, the center of the outbreak in South Korea. Adding to the political drama, in late February, a senior health official who was responsible for leading efforts against the coronavirus outbreak in Daegu admitted to being a member of the cult after contracting the virus. South Korea ultimately tested all 200,000 members of the Shincheonji Church after the church’s founder and self-professed messiah, Lee Man-hee, agreed to give health authorities a list of members under the promise that their identities would be protected.

However, Shincheonji’s initially uncooperative attitude has caused frequent friction with public health agencies in the process of further contact tracing and prevention efforts. After recognizing that religious gatherings could hamper on-going prevention efforts, the Korean government has been urging all religious communities to refrain from any type of gathering. As Prime Minister Chung Se-Kyun said in a news conference on Feb 22nd: “We particularly ask to please restrain from gathering in a small space and crowded events such as religious services even in the open air, or find an alternative way, like online.” Chiefs of local governments are also meeting with religious leaders and asking them to suspend services until the end of the outbreak.

Many religious communities have complied with the request from the government, including Catholic churches and Buddhist temples, which have suspended services and a number of Christian churches have begun offering services by moving online as well. However, some churches, especially megachurches remain unsupportive of the move. According to a newspaper poll conducted on Feb 27th, 10 out of 15 megachurches in Seoul, the capital city where about ten million people live, said they would hold Sunday services on March 1st.

Even in the midst of this serious outbreak, evidence of their contribution to the spread of the virus does not seem to have persuaded protestant Christian leaders to cease in-person services. KCDC’s investigations have indicated that these in-person services put the country at risk of further spreading the virus. Despite the government’s guideline to refrain from community events, a number of churches have continued to hold in-person services. Many pastors still insist on maintaining services, saying that the in-person service is an “untouchable” component of religious life that the government has no right to meddle in. They also stress that Christian worship has continued even under severe religious persecution throughout history. Some pastors have also tied the outbreak to their religious teachings as part of “Satan’s plot.” Moreover, the Shincheonji church and its membership have resisted the blame for the spread of the virus and portrayed themselves as a persecuted minority.

The general public’s view on Christian churches and their role in the epidemic in Korea is, in general, not favorable. On the online National Petition board of the Moon administration, there are a number of petitions to ban in-person religious services for the duration of the coronavirus outbreak. Moreover, according to a recent poll conducted by the Korean National Association of Christian Pastors and the Christianity Media Forum of Korea, 71 percent of Christians answered in favor of suspending in-person religious services. The public in South Korea appears to want the government to take a more aggressive approach to megachurches to hasten the end of the coronavirus outbreak as quickly as possible.

In spite of these warning, large church gatherings appear to be continuing. A pastor affiliated in one of the megachurches in Seoul with over 100,000 members tested positive in late February after having led a service in which more than 2,000 parishioners were in attendance. Just a few days ago, at least six confirmed cases were reported from the participants of a church retreat in which 168 individuals were involved in Seoul (this case is currently under KCDC’s investigation). On March 15th, 46 individuals were infected through a Sunday service of a church in Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do.

However, it has proven to be politically and administratively difficult for the government to exercise its power over religion. Both evidence and public opinion are favorable towards the government banning church services, but that alone does not seem to have compelled the government to act. This is in part likely because politicians in the National Assembly are hesitant to strongly criticize the Christian community ahead of the general election that will be coming on April 15th. Additionally, religious freedom is a constitutional right specified in Article 20 of the Constitution. This poses a dilemma for public health authorities as explicit banning of in-person religious services could constitute a violation of the constitution. In other words, they have to consider the rights guaranteed by law, the aftermath of the outbreak, such as an unconstitutionality suit, and whether they have enough capacity to deal with such issues. According to an official from the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (MCST):

“We cannot force religious communities to stop offering services. This is a violation of the right of religious freedom stipulated in the Constitution. Some even ask why the government is intervening in religious activities. What the government can do is coordinating with religious communities at the level of recommendation or guideline.”

What this Episode Reveals about the Growing Role of Religion as a Political Force in a Korean Society

With the rapid economic growth throughout the 1960s to the 1980s, Christianity expanded explosively in South Korea, stemming from broad social changes and the enthusiastic proselytizing effort of Christian churches. Churches have provided a new foundation for social cohesion to those who migrated from rural to urban areas in the process of urbanization starting in the 1960s. In this process, the Christian community’s aggressive evangelical movement in the 1970s and 1980s along with the localized messages guaranteeing prosperity and supernatural healing further expedited the growth of the Christian population as well.

As a result of these changes, the Christian population in South Korea is currently estimated to be about 30% of the total population–about three-quarters Protestant, one quarter Catholic, while the Buddhist and “no religion” populations are estimated at about 23% and 46%, respectively. Overall, the culture is heavily influenced by Confucian ideas, which, though not a religion, is deeply embedded in South Korean culture, even within Christian churches. While not all Protestants are members of megachurches, these churches have experienced some of the highest growth rates over the last few decades, though growth appears to be leveling off. For example, Yoido Full Gospel Church in Seoul, which is considered to be the biggest Evangelical church in the world, boasts as many as 800,000 members today. As of 2019, there are 20 churches for which the number of members exceeds 10,000.

The presence of Christian churches has become increasingly prominent in Korean politics, providing a highly mobilized, even if not entirely coherent, voting bloc. However, the political orientation across different Christian churches is diverse. For instance, progressive Christian churches in the 1970s and 1980s played a significant role in democratizing the government in South Korea by leading protestors against the dictatorship, and these churches continue to hold a more progressive human rights orientation today.

However, there were also many conservative pastors at that time, such as those associated with megachurches, who enjoyed favorable relationships with the authoritarian government. Many megachurches have continued to serve as a symbol of the Christian right in South Korea and increasingly are more aligned with the conservative party today. Like many megachurches in the US, megachurches in South Korea blend Christianity with capitalism with stories of lavish and tax-free lifestyles of Protestant leaders causing mistrust among the general public.

Korean politics is currently dominated by a politically left-of-center administration and parliament. The current administration of President Moon Jae-In was established in May 2017 with a mission of eradicating the administrative corruption that stained the previous administration, as the successor to President Park Geun-Hye, who was impeached on March 10th in 2017 due to the presidential scandal including the abuse of authority and bribery. Earlier in 2016, the conservative party lost the majority in parliament, following the general election on April 16th. President Moon has enjoyed higher public support than his recent predecessors did.

However, the former President Park Geun-Hye still has a lot of political supporters on the political right including among followers of certain megachurches. Every weekend since the conviction of the former President, rightwing activists have rallied against the current administration in Gwanghwamun, Seoul, urging the release of the impeached President Park Geun-Hye and resignation of President Moon Jae-In, with thousands of participants. The activists continued the rallies even after the city government of Seoul banned outdoor events in large squares in the city to prevent mass infection.

But thousands of Christian activists, in part mobilized by some of the megachurches, continued to hold worship-style gatherings in the rallies until the end of February, thereby risking another mass infection, even after the city government’s restriction of banning outdoor events in large squares in the city. As Rev. Jeon Kwang-Hoon of the Christian Council of Korea, who led the rallies, stated at a speech at one of the rallies “No one has been infected outdoors. God will heal us from the plague.” The events ceased only after the pastor was arrested on February 24th. But, the rallies confirmed that, for the thousands of participants, the words of one religious leader (or the organization with which he was affiliated) were more influential than the fear of coronavirus infection or government guidelines.

The coronavirus outbreak has once again highlighted the influence of Christian churches that have grown in Korean society. Even though the government is seeking the cooperation of the churches to suspend in person gatherings to mitigate the outbreak, such efforts may not affect the behaviors of many Christian churches. They are too fragmented by tens of denominations to form unilateral compliance to the policy, unlike Buddhist temples and Catholic churches, which have relatively strong headquarters that promptly ordered the suspension of in-person gatherings at the initial stage of the outbreak. Many churches still insist on in-person services for the sake of their religious faith. Even, the United Christian Churches of Korea, which represents protestant Christian churches in South Korea, is urging the government not to intervene in religious activities. This has led to many people, in particular elderly people, visiting the churches on weekends and to subsequent conflicts with nearby residents who are afraid of another outbreak.

Lessons for Disease Response: Religious Liberty and the Public’s Health

While freedom of religion is embedded in the Korean constitution, historically these conflicts have not featured as central political struggles in Korean politics. However, the response to COVID-19 has served to highlight these simmering tensions. Of course, conflicts between public health practices and religious liberties, including during infectious disease outbreaks, are not new. Epidemics throughout history have been interpreted by some as a punishment from God. The black death contributed to the rise of the flagellant movement, a collective behavior aimed at salvation through self-flagellation in times of crisis that was widely criticized by the Catholic Church as well as the persecution of Jews believed incorrectly to be responsible for the spread. In contemporary examples, Zika has raised tensions between restrictive abortion laws grounded in religious opposition and the potential for unsafe abortion practices. The 2014 Ebola outbreak highlighted tensions between traditional and religious burial practices and the necessity of disposing of bodies in a sanitary manner. More broadly, religious groups across countries have routinely sought vaccine exemptions, tried to influence the content of sexuality education and sought to moralize responses to HIV, while at other times working more productively with public health officials to promote public health.

South Korea is no exception in this COVID-19 outbreak. But beyond that, the coronavirus outbreak has revealed the implicit power of megachurches in South Korea and tensions between public health and religious liberties, with megachurches often prioritizing martyrdom over protecting the public and parishioners against an epidemic crisis. South Korea’s government is wavering between the necessity of protecting religious freedom of the protestant Christian community and the resolution of the public health crisis that the public at large.

An encouraging development is that the number of churches suspending in-person services is increasing. The government’s effort appears to be paying off without the need for coercive action. However, the risk of an in-person church service generating another super spreader event remains high.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments