This is a guest post from Andrew Yeo, who is an Associate Professor of Politics at The Catholic University of America in Washington DC and a Fulbright Visiting Research Fellow in the Department of Political Science at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His most recent books include Asia’s Regional Architecture: Alliances and Institutions in the Pacific Century and North Korean Human Rights: Activists and Networks (with Danielle Chubb).

As a US scholar on research leave in Manila, I’ve been following the COVID-19 response in both the Philippines and the United States closely. I was bemused last weekend reading headlines about anti-quarantine protestors in several US state capitals, and the outrage geared at (what I presume to be) mostly Trump supporters in risking the further spread of the coronavirus.

Having experienced a different reality here, I’ve pondered the pros and cons of stricter quarantine enforcement as we have seen in the Philippines. Would either country envisage the imposition of martial law, a growing concern among some in Manila as the Philippine National Police (PNP) and Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) boost their presence?

What Strict Enhanced Community Quarantine Looks Like

After resisting banning flights from China and calls for an early selective lockdown for over a month, in mid-March, the number of COVID-19 cases jumped from less than a dozen to 140. In response, the Philippine government placed Metro Manila, and later the entire island of Luzon (the largest island group in the Philippines) under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) on March 15, 2020. Since then, ECQ for Luzon has been extended twice (currently until May 15).

Like many other parts of the world, the measures have prohibited mass gatherings, shuttered most businesses, and halted public transportation except those deemed essential such as groceries, pharmacies, and banks. For our family, quarantine has meant staying indoors, juggling personal and professional responsibilities, and schooling our two young children from home. As noted in an earlier Duck post, however, during crises, it is the poor who suffer disproportionately. The daily struggles for many Filipinos who live a hand to mouth existence are serious, and the distribution of government aid has been slow and inadequate.

For this reason, some experts speculated that after a month of lockdown, restrictions might be eased with some businesses reopening. However, in Metro Manila (I can’t speak for provinces outside of Luzon where ECQ has reportedly been more relaxed), enforcement has become much stricter in recent weeks as the number of COVID-19 cases surpasses 7,000. This was evident when police arrested joggers in my neighborhood violating the ECQ. And to our dismay, four fully armed PNP officers entered our condominium (a private residence) on reports that residents were breaching social distancing rules. In the first two weeks of the ECQ, the PNP had already arrested over 17,000 violators. Quarantine violators can face immediate arrest without warning. The AFP has also been on standby to “prepare for strict implementation” of the lockdown.

Strong (Authoritarian) Leadership

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is no stranger to authoritarian tactics, and his response to COVID-19 is no exception. During a national speech, Duterte, speaking with his usual bluster, called on police and the military to shoot down violators of the ECQ. For extra measure he added “I’ll send you to the grave. … Don’t test the government.”

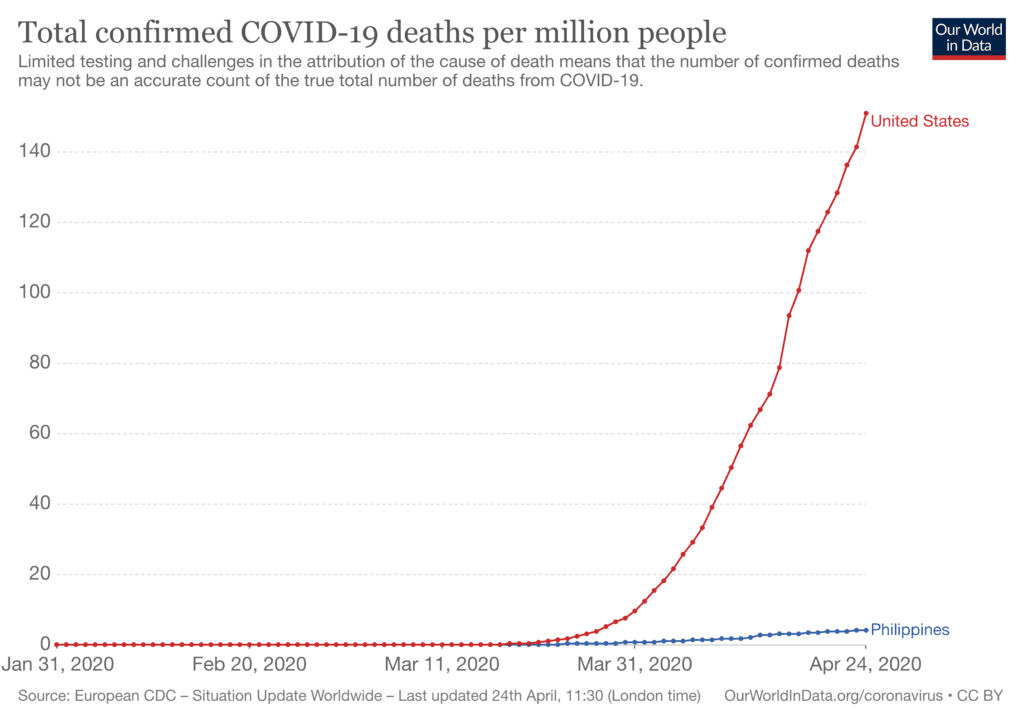

The militarization of the Philippine response to COVID-19 is unsurprising. Three former generals in their now civilian capacities lead the Philippines National Action Plan on COVID-19. Critics have likened Duterte’s approach to an “undeclared martial law.” Casting aside criticism, however, the Philippine government has thus far managed to contain the spread of the virus, or at least given the semblance of tackling COVID-19 head-on, despite a significant shortage of testing kits and personal protective equipment.

Duterte, who remains widely popular in the Philippines, has support from parliament as well. On March 23, the Philippines signed Republic Act 11469, also known as the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act as explained in this excellent primer put together by my colleagues at the University of the Philippines. Declaring a national emergency, the Act grants the President special powers for a limited time. Unlike the US where authority has vacillated between federal and state governments on COVID-19 response, Section 4 of the Act “authorizes the President to ensure that all local governments act within the letter and spirit of and are cooperating fully with the directives and regulations of the national government specific to the implementation of the enhanced community quarantine to address the COVID-19 emergency.”

The Costs and Efficacy of Community Quarantines

On one hand, early implementation of the ECQ and its strict enforcement, even at the cost of inflicting economic pain among the most vulnerable, appears to have slowed the spread of COVID-19, likely saving thousands of lives. On the other hand, based on past actions such as Duterte’s response to the Philippine drug crisis, legitimate concerns exist that stricter quarantine enforcement may lead to an increase in human rights abuses. This was underscored by the recent shooting of a Filipino with mental health issues at a quarantine checkpoint. More importantly, strict ECQ enforcement alone will not counter a pandemic without increased testing, contact tracing, and boosting the capacity of local health systems. The Duterte government is now at a crossroads as it pushes ahead with stricter ECQ enforcement in Metro Manila and other provinces, but relaxes the ECQ in regions with lower reported COVID-19 cases.

Although Manila and Washington were both initially slow to respond to the coronavirus threat, in the US, the Trump administration still lacks the type of strong, national response to COVID-19 observed in the Philippines. Then again, most Americans, whether progressive or conservative, would likely reject the strict type of ECQ measures implemented in Manila. In fairness, major differences in state capacity and health systems makes for a difficult comparison in COVID-19 response between both countries. Nevertheless, seeing images of anti-quarantine rallies in the US raises the question if clear federal guidelines and stricter quarantine measures in some regions might save more lives moving forward.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks