This is a guest post from Collin Meisel and Jonathan D. Moyer.

Collin Meisel (Twitter: @collinmeisel) is a Research Associate at the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures and a veteran of the U.S. Air Force. At Pardee, Collin works with the Diplometrics team to analyze international relations and build long-term bilateral forecasts for topics such as trade, migration, and international governmental organization membership.

Jonathan D. Moyer (Twitter: @moyerjonathan) is Assistant Professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver and Director of the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures. For the last 15 years, Jonathan has used long-term, integrated policy analysis and forecasting methods to inform the strategic planning efforts of governments, international organizations, and corporations around the world, including sponsors such as USAID, the African Union’s New Partnership for Africa’s Development, and the UN Development Programme.

As COVID-19 disrupts life the world over, many of the pandemic’s long-term consequences remain uncertain. However, using multiple long-term forecast scenarios, one geopolitical consequence is beginning to come into focus: COVID-19 is accelerating the transition in power between the U.S. and China. Despite assertions from political scientist Barry Posen that COVID-19 “is weakening all of the great and middle powers more or less equally,” economic and mortality projections suggest that China will see material gains relative to the U.S. that could translate into broader geopolitical gains.

Quantified in terms of the distribution of relative material capabilities, China’s forecasted gains are roughly the magnitude of the current relative global capabilities of Turkey.

What do we mean?

Power is a relative concept, always requiring a comparison of capabilities across at least two actors. For example, Pakistan’s gross domestic product (GDP) of 254 billion dollars (constant 2010 USD) was more than ten times the GDP of Afghanistan (21 billion) in 2018. At the same time, however, Pakistan’s GDP paled in comparison to India, which had a GDP of 2.8 trillion. As such, Pakistan might have held significant economic sway over its northwestern neighbor while failing to hold a candle to its neighbor to the southeast. Depending on what you are comparing it to, 254 billion dollars affords you either a lot or very little in terms of relative material capabilities.

The relative material capabilities that matter in the international system are multidimensional and stretch across economic, security, and diplomatic variables. Together, they can be used as a proxy measure for national power. Power itself is difficult to measure—the fact that a country wields more capabilities does not necessarily translate into favorable outcomes all the time; however, it often translates into favorable outcomes more times than not relative to less powerful opponents.

What do models suggest the effect of COVID-19 is on the distribution of material capabilities?

Using the International Futures (IFs) integrated assessment model—which has been employed widely to assess issues of geopolitics, security, and the economy—we constructed scenarios that draw upon the research of others to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the distribution of power in the international system. Our analysis compared six simulations of global development using assumptions based on recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) growth forecasts—allowing for baseline and faster or slower economic recovery—and various mortality projections, where the latter were determined by an extrapolation of current disease case counts.

In particular, we examined the effect of between 93,000 and 334,000 COVID-19-related deaths for the U.S. in 2020 and between 20,000 and 80,000 deaths in China. Our baseline scenario, which assumes 40,000 COVID-related deaths in China, is a ten-fold increase from the current official count. For the U.S., we assume 175,000 COVID-19 deaths through the end of 2020 as a baseline projection. This is just under double the current official case count and roughly in line with current projections from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, which projects between 115,000 and 207,000 COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. by August 4, 2020.

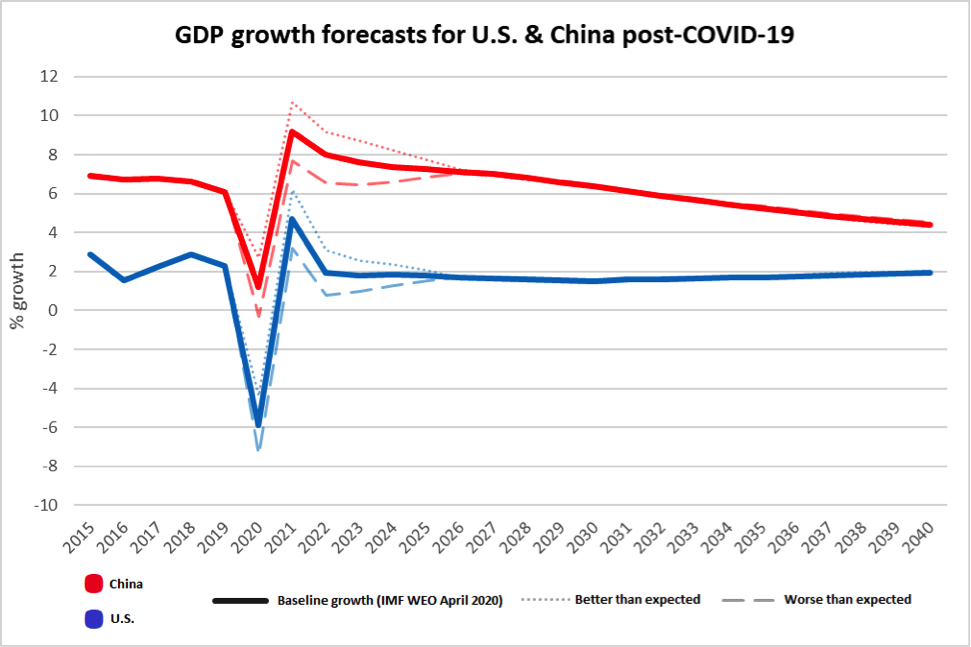

The IFs tool’s real GDP growth projections, shown in the figure above, illustrate that the U.S. (in blue) is expected to take an outsized hit relative to China (in red). In absolute terms, this results in Chinese GDP at market exchange rates surpassing the U.S. between one to two years earlier than previously projected (2025 or 2026 vs. 2027).

Qualitatively, expert opinion regarding the long-term relative effect of COVID-19 on Chinese economic dominance is mixed. Still, short-term indicators for certain elements of China’s economy, such as manufacturing, have begun to show signs of economic recovery while the rest of the world lags behind. For example, China’s Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) score—a metric designed to assess the health of a country’s manufacturing sector, where a score above 50 indicates expansion while a score below 50 indicates contraction—moved into expansionary territory in both March (52) and April (50.8) after a severe contractionary dip (35.7) in February. Meanwhile, the U.S. PMI score has remained in contractionary territory since March, standing at 49.1 and 41.5 the past two months.

Similar to recent analysis from RAND and prognostications from Secretary of Defense Mark Esper, our forecasts also suggest that the U.S. military will see increased budgetary constraints compared with a pre-COVID-19 world. While we forecast that China will see a reduction in military spending relative to pre-COVID projections (a likely prognosis for its Southeast Asian neighbors as well) that are between $13B and $49B each year through 2030 in our worst case scenario, it is less than the worst-case reduction that we forecast for the U.S. (between $58B and $94B each year). For our forecast to play out differently, U.S. military spending as a percent of GDP (hovering just above 3 percent in recent years and higher than China’s projected military spending as a share of GDP across this time horizon) would need to increase significantly.

While the COVID-19 forecasts display differential impacts on Chinese and U.S. development across other areas as well, these effects are relatively smaller than those of COVID-19 on the distribution of economic production and military spending.

What happens when these factors are considered together?

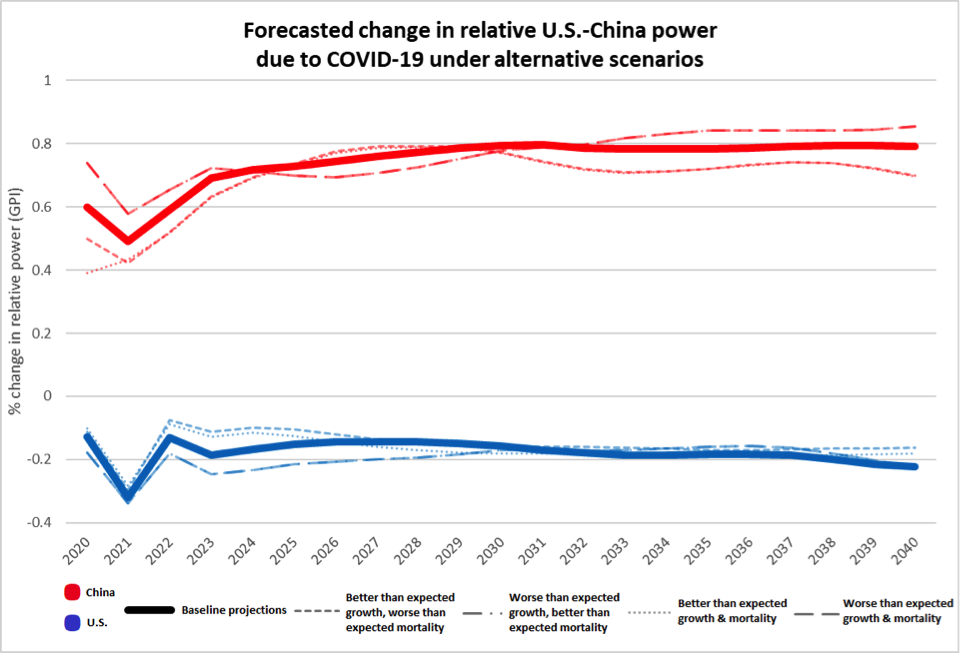

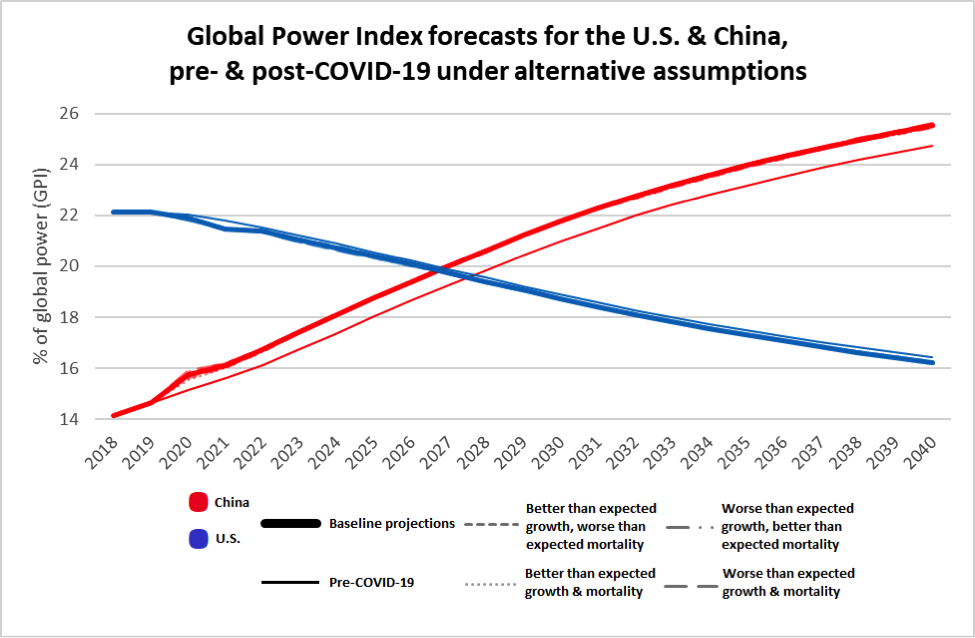

When exploring how the distribution of these relative measures of material power changed the distribution of the Global Power Index (GPI)—a composite measure of material capabilities previously featured in the National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends 2030 report—the results suggest that China (below in red) will gain approximately one percent of global power relative to the U.S. (in blue) by 2030. This share of global power is similar to the relative capabilities of Turkey today.

It’s worth taking a moment to unpack this conclusion. The global sum of GDP, military spending, and other gross measures of material capabilities will continue to grow in the coming decades. Because relative power is a measure of a country’s share of the global total, our forecast translates to an absolute gain in material capabilities for China relative to the U.S. that is even larger than the sum of material capabilities possessed by Turkey today.

Quantifying some of the core components of GPI (which comprises 11 subcomponents in total), China’s absolute gains relative to the U.S. in 2030 in our baseline scenario are equal to an additional: $904B in GDP; $168B in trade; and $38B in military spending. Such is the cost of COVID-19 to U.S. power.

For China’s gains in relative power to be erased in our baseline scenario (displayed above in thick red and blue lines), its annual growth would need to undershoot currently forecasted values by roughly 2 percentage points each year for the next decade. In fact, given that these forecasts do not account for the current shock to the global oil market—a shock that is likely to harm the net oil-producing U.S. more than the net oil-consuming China—the hit to Chinese economic growth would likely need to be even greater for China to not gain power relative to the U.S. post-COVID-19.

The reality is that economic growth is the primary driver within these scenarios. Thus, even if we were to assume much higher case count within China—in an earlier analysis we assumed two percent of each country’s population becomes infected with COVID-19—China would likely see only somewhat smaller gains (~0.7 percent) in global power relative to the U.S.

Why does this matter?

Countries with the preponderance of global material capabilities have been wont to shape the international order in their image. This was true of the United Kingdom’s imperialist approach to interstate relations as well as the American-led order that followed (former Secretary of State Dean Acheson famously reflected that he was Present at the Creation).

What might a Chinese world order look like? The WHO’s cold shoulder to Taiwan and its 24 million citizens during the worst pandemic in a century provides one relevant anecdote that can help to answer this question. The Chinese Communist Party’s imprisonment of over one million Uighurs provides another. On a more positive note, President Xi Jinping’s recent promise to treat any Chinese-produced COVID-19 vaccine as a “global public good” presents an air of magnanimity that has recently been conspicuously absent from the foreign policy of the world’s current hegemon, the U.S.

Meanwhile, we are already transitioning to an international system that is characterized by increasingly entrenched bipolarity. From the perspective of balance-of-power theorists, this could turn out to be a positive development. Regardless, China will get its way more moving forward, particularly within its own back yard. This reality has been a long time coming. From the perspective of future historians, however, it is likely that “COVID-19 will come to be seen as a chapter break,” as Robert Kaplan recently observed.

Does this mean that the Chinese Century will inevitably dawn much sooner and much more abruptly than expected?

Not necessarily. There are many factors that should be considered when broadly assessing the rise of one country relative to another. The U.S. will retain significant advantages in many aspects of international relations that remain difficult to quantify or include in an index of this type (remaining the reserve currency of choice, for example). Additionally, measures like these do not capture network effects, especially the strength of alliance systems. Finally, the relative distribution of material capabilities does not include the quality of their use: governments can squander opportunities or leverage them. Where broad measures of material capabilities are concerned, however, the picture is clear: COVID-19 is closing the gap in relative capabilities for the U.S. and China and accelerating the U.S.-China transition.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks