This is a guest post by Manali Kumar, incoming Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland). Her research focuses on prudence in statecraft, and India’s national identities and interests as a rising power. She can be found on Twitter @manalikumar.

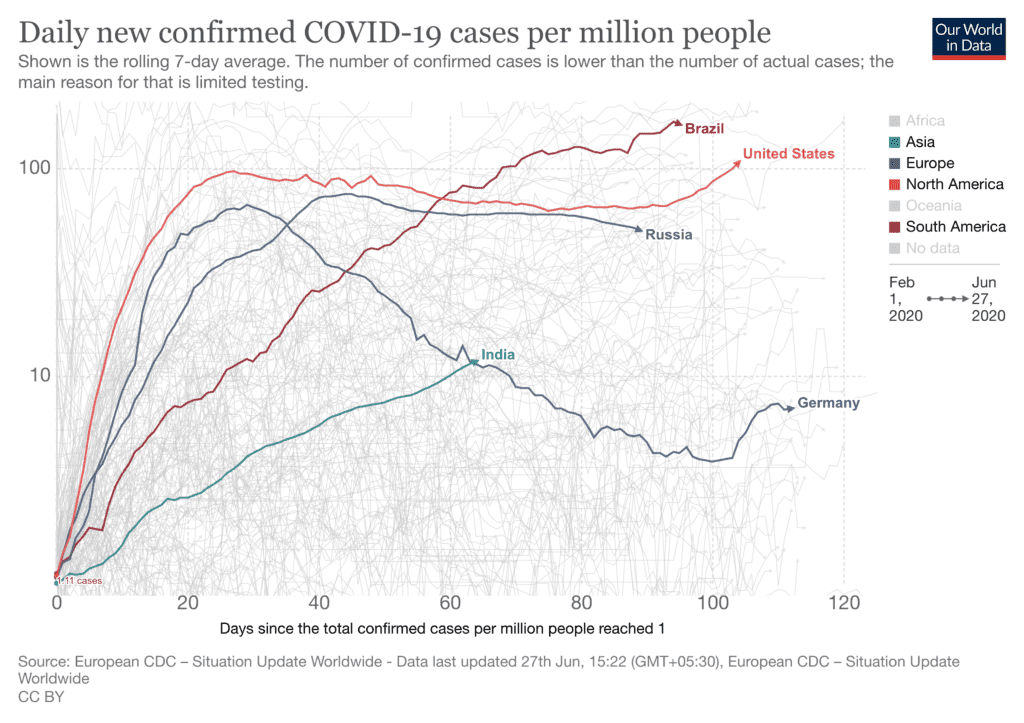

Despite one of the strictest nationwide lockdowns in the world, which lasted for 68 days before the government started easing restrictions on 8 June, the COVID-19 pandemic has continued to spread in India. Although the country’s international borders remain closed, domestic travel has resumed and shopping malls, restaurants, and places of worship have re-opened. Yet, the number of infections has continued to increase and India now has the fourth-largest number of confirmed cases in the world.

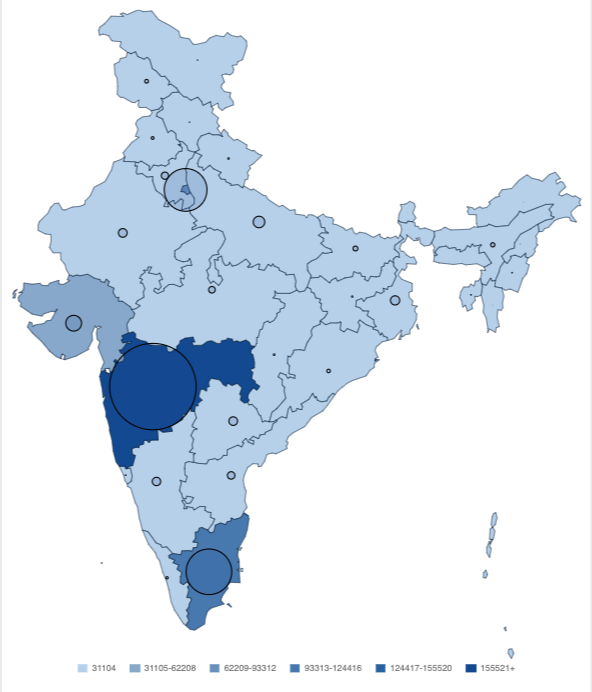

Three major cities – Mumbai, Delhi, and Chennai – are the worst affected and together account for more than half of all cases in the country. None of these cities is believed to have reached its peak yet. Meanwhile, stories of people being denied treatment are becoming more common, even as doctors have been warning that the country is on the brink of running out of hospital beds. The central government has devised a policy of patchwork quarantine zones to contain particular outbreak clusters, but many of India’s political leaders have come out strongly in favor of opening up the economy.

Source: NDTV

How did India’s situation flip from an initial sense of hope due to quick and decisive action early at the start of the outbreak to one of an impending sense of doom as the pandemic seems all but out of control? As we evaluate outcomes so far and consider how things may evolve in the coming weeks, leadership looms large as an important variable. Here, I draw on Weber’s ‘Politics as a Vocation’ lecture, delivered a hundred years ago, to explore Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership of the coronavirus pandemic in India.

Only Power Backed Up By Violence

Narendra Modi is a demagogue whose authority is legitimized based on his charisma. A skilled rhetorician and orator, he has presented himself as a son of the soil, a humble tea-seller who has worked his way to the top leadership role in the country. He peppers his speeches with lofty Sanskrit phrases and liberal humanist ideals, promises strength, development, and prosperity, but evades directly discussing crucial policy issues. In six years as the country’s prime minister, Modi has never held an open press conference and faced questions from the press. He successfully exploits the emotions and prejudices of Indians, and commands devotion from his supporters: millions enthusiastically banged pots and pans on 22 March following an appeal from him, and switched off their lights and lit candles on 5 April.

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) rule at the center has been accompanied by a decline in deliberative democracy, an increase in public manipulation, and the use of fear to deter criticism. Modi and other BJP leaders routinely engage in lying, denying economic and political realities, scapegoating minorities, and vilifying victims. Just in the past few months, at least 55 journalists have been arrested or had police reports filed against them for their coronavirus reporting. The continued incarceration of pregnant Muslim student activist Safoora Zargar during the pandemic based on allegations of involvement in the riots in Delhi this February grabbed national media attention this month. The BJP’s vast network of IT cells and internet trolls serves as today’s ‘political publicist’; its WhatsApp group, for example, has over 3.2 million subscribers. The party and the wider network of Hindu nationalist organizations known as the ‘Sangh Parivar’ aid the task of organized domination. Any criticism of government policies is a criticism of Modi, and any criticism of Modi is a criticism of India.

Pathological Imprudence in Policymaking

Weber identified three ‘pre-eminent qualities’ for the politician: a passion for the cause (whatever that may be), a feeling of responsibility for the consequences of one’s actions, and a sense of proportion. Modi administration’s pandemic policymaking is a case study in the pathologies of demagogic leadership. The lockdown, announced and implemented exactly like the surprise demonetization policy of November 2016, lacked proportion and might prove to be irresponsible after all. It lacked foresight in its inability to anticipate the biggest migration crisis in India since the partition of 1947, a tragedy made all the worse by the government’s failure to use the time provided by the lockdown to ramp up health care capabilities. There are serious lags, deficiencies, and shortfalls in testing and tracing, and therefore insufficient data about the prevalence and dynamics of the disease in India, and hospital capacity has only increased piecemeal.

The central government’s lack of ‘objectivity’ – of “doing what needs to be done” – is compounded by its rejection of expert knowledge, reluctance to share data and information, and absence of transparency. Epidemiologists with the government taskforce have criticized the mathematical model used by their chairperson, and analysts have accused the government of using incomplete data to justify its decision to lift the lockdown. Relevant government agencies such as the Health Ministry’s Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP), which is responsible for tracking the spread of infectious diseases, have been excluded from pandemic policymaking. Six Indian medical associations recently released a public statement criticizing the government’s ‘incoherent’ lockdown strategy.

Likewise, the government’s $265 billion stimulus package announced on 12 May has been widely criticized as inadequate for stimulating domestic consumption. Recent estimates suggest that 12 million people may have been pushed into extreme poverty during the lockdown. Another study estimated that 84% of households suffered a decrease in income and over one-third of all Indian households were expected to run out of resources by the end of May. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy estimates that unemployment was above 23 percent in April and May, up from 7.8 percent in June 2019. Yet, the stimulus package does nothing to help millions of Indians who have lost their incomes – there are no cash handouts or paycheck protection programs. Modi pays no mind to the responsibility of not “burden[ing] others with the results of his own actions”.

The Modi administration’s approach to decision-making precludes prudent judgment. Prudent policymaking is deliberate. It involves formulating context-specific responses using reflective reasoning informed by experience to pursue long-term wellbeing through moderate actions that can adapt to changing circumstances. However, “micromanager-in-chief” Modi has concentrated decision-making within the Prime Minister’s Office and policies are made by a select group of senior party members and handpicked advisors. “Minimum government, maximum governance” is the mantra used to rationalize the rejection of consulting bureaucratic and outside expertise. This, combined with an emphasis on policy ‘masterstrokes’, that can easily be turned into PR campaigns, limits the scope for deliberation and reflection and prevents the identification of errors of reasoning, biases in assumptions, and policy blind spots.

They Have Not Measured Up

Each day’s tally of new cases breaks the previous day’s record, and sadly, this pandemic is not the only disaster India has experienced this year. In the 14 weeks since the lockdown began, a chemical gas leak in Vizag caused non-fatal injuries to hundreds of nearby residents in May and an exploded oil well in Assam has been burning since early June, releasing a continuous stream of natural gas and displacing thousands of people. Cyclone Amphan left a trail of destruction across the east coast, Mumbai was hit by its first cyclone since 1948, and locust swarms have attacked parts of northern India. Refusing to acknowledge the consequences of these disasters is not going to make their costs go away and it compounds suffering.

At the start of the crisis, the administration won accolades for its pharmaceutical diplomacy and efforts to revive regional solidarity in South Asia in March and April. In his speech on 12 May, in which he announced the stimulus package, Modi resolutely stated it was India’s responsibility to claim the 21st century. He proudly announced that India’s ability to turn any crisis into an opportunity would now aid the “magnificent building of self-reliant India”. However, cross-border fighting with Pakistan in May followed by an unprecedented deterioration in relations with Nepal and the worst escalation in the border dispute with China in June have soured what was supposed to be India’s coming out moment as a global leader.

Our research about India’s national identity discourses shows that public disappointment with the country’s leadership – especially due to corruption, vote-bank politics, and inefficient bureaucracy – has been increasing since 1980. The BJP successfully exploited this discontent to emerge as a credible alternative to the Indian National Congress (INC), which had dominated Indian politics since independence. In 2010, the optimism of the ‘India shining’ narrative reflected pride in the talent and creativity of Indians despite its incompetent government and inefficient bureaucracy. Modi’s phenomenal success in 2014 was in large part due to his rhetoric that blamed the decade-long government led by the INC and promised a smart new alternative, which appealed to voters beyond the core group of Hindutva supporters.

Much of that optimism appears to have dissipated a decade later. It is worth remembering that nationwide protests related to a controversial citizenship law that had spread across India beginning December 2019 came to a pause only after the lockdown was announced on 24 March. The sources of that discontent have only been exacerbated during the crisis – Muslims have been blamed for spreading the epidemic; patients been segregated based on religion; and BJP lawmakers have called for boycotting Muslim vendors.

“The following”, Weber warned, “can be harnessed only so long as an honest belief in his person and his cause inspires at least part of the following”. With the spreading disease, rising poverty, and an economy in distress, Modi stands to lose his centrist supporters. The BJP’s core group of supporters would perceive any loss of territory to China in the current border standoff as a loss of honor. What does the future hold for a country that’s home to a fifth of the world’s population experiences disease, hunger, division, and demagoguery? That’s a grim question to ponder for a citizen with political science as a vocation.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments