This is a guest post by Ryan Lloyd, a Visiting Assistant Professor of International Studies at Centre College. His research focuses on comparative political behavior and vote buying, particularly in Brazil. He can be reached at lloydr418@gmail.com, and on Twitter at @Lloyder2323.

Public health and political crises

The numbers were disastrous. After months of denialism, Brazil had just passed Italy into third place for official deaths related to COVID, and was hot on the UK’s tail, with 35,930–more than 1,000 were dying per day. And despite massive undercounting of cases, it was already in second place with 672,846.

So on June 7, President Jair Bolsonaro took drastic action. He told his health ministry to stop counting.

Since then, the Supreme Court has ordered the federal government to release coronavirus data again, and a consortium of media outlets has banded together to release their own figures, collected directly from state health agencies. Brazil has now passed 1 million cases and 50,000 deaths with no end in sight, two health ministers sacked.

The true number, however, is far worse, with the number of cases being underestimated at least sevenfold, and 2.6% of the population having COVID antibodies, with the percentage in some Northern and Northeastern cities reaching 15%-25%, according to a nationwide study conducted by the Federal University of Pelotas in Brazil. A military officer is the interim health minister, and he has attributed the North and Northeast’s coronavirus woes to the Northern hemisphere’s winter (they are unequivocally not, not least because the North and Northeast are in the Southern hemisphere and the Northern hemisphere is not in winter).

Meanwhile, a political crisis is adding to the country’s woes. After months of brinkmanship with Congress and the Supreme Court, tensions within Bolsonaro’s own cabinet came to a head with the resignation of his popular Minister of Justice, Sérgio Moro. Moro accused Bolsonaro of meddling in an investigation into his family in Rio de Janeiro, which led to investigations by the Supreme Court and the public release of the videotape of a foul-mouthed meeting in which Bolsonaro threatened to replace him if he did not interfere in the investigation.

This has led to protests and counter-protests despite the pandemic, both against Bolsonaro and against the Supreme Court. In the past week, tensions have risen even further, with Fabrício Queiroz, a family friend who has been implicated in a corruption scheme involving Bolsonaro’s son and criminal militias in Rio de Janeiro, being arrested in a dramatic police raid on Bolsonaro’s lawyer’s home.

Bolsonaro’s Popularity

Amid all the excitement, as a president with weak democratic commitments encourages confrontations with the other branches of government, one question rises to the forefront: how much support does Bolsonaro have?

One might imagine that the mishandling of the coronavirus crisis and the economy would have hurt him, much less the political conflicts. But if so, how badly? This is an especially important question given the collision course between Bolsonaro and his rivals: if Bolsonaro disobeys a ruling from the Supreme Court, for instance, will he find support in the streets?

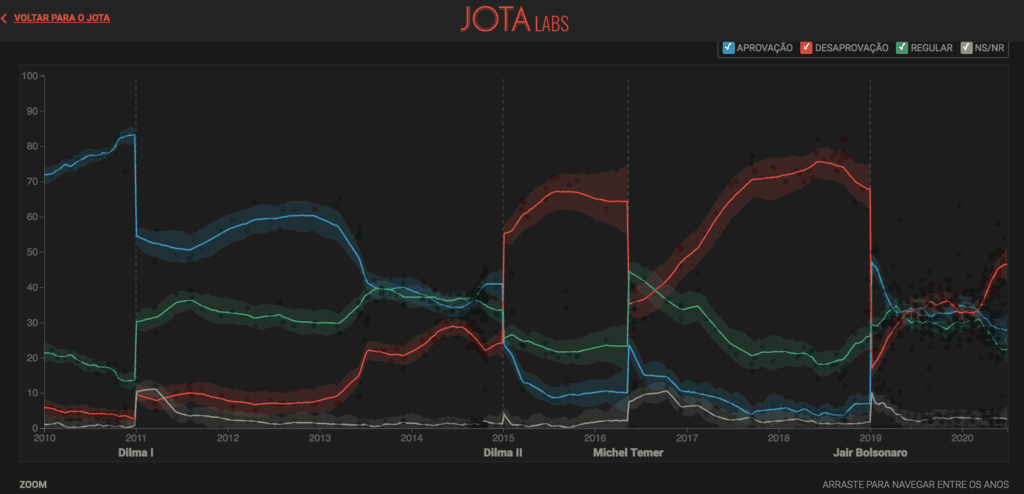

The short answer is that it is difficult to know. From a comparative perspective, we can see that Bolsonaro has at the very least done poorly in comparison to other leaders dealing with the coronavirus outbreak. With the exception of Donald Trump, most world leaders, from Emmanuel Macron to Justin Trudeau, experienced a bump in popularity through May as part of a rally-round-the-flag effect, although it’s difficult to know how long they will last. As one can see from the approval-rating aggregator from the Brazilian news site Jota, Bolsonaro certainly has not experienced a bump, with approval ratings falling and disapproval ratings climbing since March.

Yet Brazil’s polling industry suffers from some particularities that make it difficult to know how much Bolsonaro has been hurt by these scandals.

According to the Brazilian Polling Error Database, which was assembled for a working paper with Mathieu Turgeon of the University of Western Ontario, Brazilian polls tend to have a low baseline of accuracy, even for presidential elections (an average absolute polling error of more than 5% for up to a week away from first-round elections between 2002 and 2014).

This can be attributed to a variety of factors, including the difficulty of gaining access to a variety of populations in Brazil. Virtually all polling institutes have traditionally used face-to-face interviewing, which presents a problem: it is difficult to gain access to either the very poor or the very rich. Interviewers cannot access the most remote areas of the country, while they are not given access to some urban slums and exclusive upper-class condominiums.

Traditionally, polling firms have faced a difficult choice on how to deal with this problem. One of the main polling firms, Datafolha, prefers to use ponto de fluxo polling, or putting interviewers in public areas with heavy foot traffic and interviewing passersby. Going door-to-door, its General Director said in 2010, would take too long, causing results to be out-of-date before they are even published. Their main competitors, Ibope, prefer to go door-by-door anyway, despite possible time lags. Both of them, however, look to correct for possible sampling difficulties by using quotas, although at different stages of the sampling process; these quotas are usually sex and age, but can sometimes include education and occupation.

Polling amid a pandemic

The pandemic has thrown the Brazilian polling industry into uncertainty. With the difficulty of sending strangers to talk personally to respondents, whether in public areas or in their houses, polling firms have found themselves forced to quickly move to telephone surveys.

We do not have any reliable access to how many polls measuring approval ratings have used telephone and how many have used some sort of face-to-face measure. However, thanks to the help of Julio Trecenti, a brilliant PhD student in statistics at the University of São Paulo, we do have access to data on how many polls for the 2020 municipal elections are polling by phone, as they have to be registered with the Superior Electoral Tribunal. Indeed, the number of polls being conducted by phone has indeed increased noticeably since March, when the coronavirus began to make more of an impact on Brazil.

This lack of familiarity with telephone polling poses big nationwide polling companies with a problem. The degree of penetration for landlines has always been relatively low, and whatever lists of cell phone numbers have been obtained from private companies often come with no guarantee of random sampling. In addition, around 90% of respondents refuse to respond to telephone surveys, while only about 20% refuse to respond to face-to-face interviews. Internet polling has never caught on either, partially due to the inconsistency of many Internet connections.

This has led to widely differing evaluations of Bolsonaro’s popularity. According to Jota’s aggregator, for instance, one poll from Offerwise on June 13 had Bolsonaro’s approval rating at 35.1% and his disapproval rating at 41.6%, while Quaest measured them on June 17 at 21% and 54%, respectively.

This variation in polling results even reached the mainstream press, with recriminations between rival polling firms Atlas and Datafolha surfacing in El País’ opinions page in late April after their approval rating estimates for Bolsonaro had differed widely. Andrei Roman, the CEO of Atlas, pointed out that, even after weighting, a significantly higher percentage of respondents in Datafolha’s sample had said they had voted for Bolsonaro in the 2018 election than had voted for him nationwide, which likely biased Bolsonaro’s approval rating in their poll upwards. Datafolha responded by noting that recollection of past voting choices is often unreliable, and criticized Atlas for using online polling rather than telephone polling.

They both might be right. This type of polling is new for many Brazilian firms, and much of their difficulties likely come from having lists of telephone numbers that are not representative of target populations. Firms therefore have to adjust the samples in some way to make them representative, but they are finding different, imperfect ways in which to do it. This is why polls are giving such varying numbers about Bolsonaro’s popularity.

Brazil: Poised on a Knife Edge

Why does all this matter? Besides the normal effects of public opinion on chief executives’ ability to govern, Bolsonaro’s tenure as President depends on Congress because of how the impeachment process works in Brazil (see below). In particular, he is beginning to cast his lot with the Centrão, a bloc of old-style patronage politicians in Congress who abandoned President Dilma Rousseff in 2016, but were central to President Michel Temer’s survival in 2017 during corruption investigations.

This means that Bolsonaro depends on how congressmen calculate their own chances of re-election, and whether they feel that they are more harmed by an association with Bolsonaro, or more helped by the exposure and largesse that high-level public appointments will provide for their re-election campaigns. Temer was willing to spend big to avoid impeachment, while Rousseff was not willing to pay out as much in earmarks and was therefore abandoned.

So, what do we actually know about Bolsonaro’s popularity? Not as much as we might hope. He seems to be doing badly in the polls, but we don’t know how badly: it could be either a mediocre figure or a disastrous figure. If it is the former, a confrontational style could yield results among his diehard support and leaners. If it is the latter, chest-thumping could lead to an evaporation of support for Bolsonaro, among both the public as a whole and the key constituencies that could decide the outcome of an impeachment process.

The difficulty, however, is that uncertainty and misperception about one’s opponent’s strength can lead to political actors taking outsized risks and entering into conflict, even when neither participant actually wants that conflict. On June 17, after the Supreme Court authorized investigations against his allies, Bolsonaro accused them of overstepping their bounds. “The time is coming when everything will be put in its rightful place.” What that place might be, both for him and the country, remains worryingly vague. Since Queiroz’s arrest, he has retreated and redoubled his bets on the Centrão, hoping that their (handsomely remunerated) support will be enough to defeat a possible impeachment vote in the lower house.

Will this be enough to sustain him in office? Will Bolsonaro oscillate once again towards fighting talk or, considering his removal from office probable, pursue more aggressive extralegal options? No one knows at this point, and the lack of a clear polling picture is not helping.

A Postscript: Impeachment?

Leaving aside the possibility of a coup or other extralegal processes for or against Bolsonaro, there are three main ways for Bolsonaro to be constitutionally removed from the presidency. Two of them depend directly upon Congress’s willingness to act. First, the election of Bolsonaro and his Vice-President, retired General Hamilton Mourão, could be annulled by the Superior Electoral Tribunal (TSE) if they rule that electoral crimes were committed during the 2018 election. One motion to annul the election was already rejected, but five others remain to be judged, including one high-profile case regarding an operation to disseminate fake news that was allegedly financed by the Bolsonaro campaign. These investigations are essentially black boxes, and it is not clear how much the TSE responds to public opinion.

The other two constitutional avenues involve Congress. The first is impeachment for a crime of responsibility: violating the President’s responsibilities as outlined by the Constitution. This would require a ⅔ vote in the lower house, which would suspend the President for 180 days, followed by a vote in the Senate, which would decide on whether to remove the President from office permanently. This is precisely what happened to President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. The second is impeachment for a crime in the traditional sense–a violation of penal code. If the Supreme Court believes that a crime has been committed, it can request that the lower house allow it to judge the case. If ⅔ of the lower house agrees, then a simple majority of the Supreme Court can remove the President from office. This is what the lower house did not allow in 2017 on two cases for President Michel Temer, despite approval ratings that bottomed out at one stage around 3%.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments