Whether scholars embed policy recommendations in their work is a flawed measure of whether work is policy-relevant.

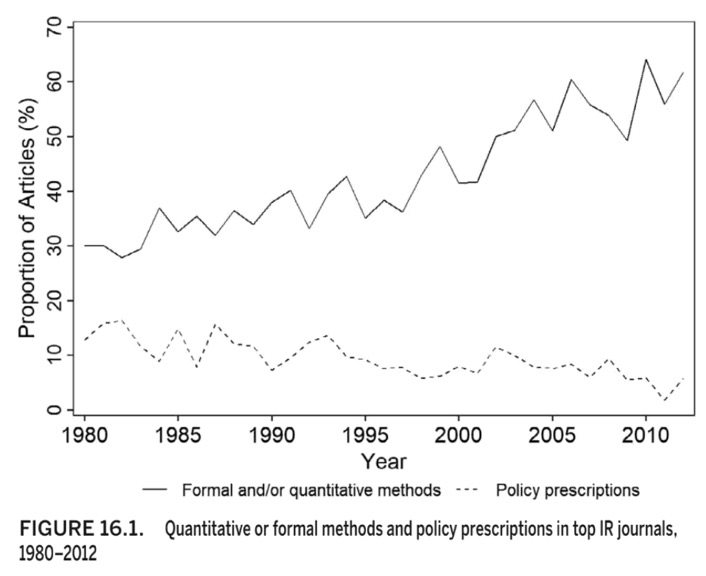

Across a series of articles and book chapters, Michael Desch and Paul Avey have argued international relations scholarship is declining in policy relevance, with IR scholars falling into what Stephen Van Evera has called a “cult of the irrelevant”: a hermetically-sealed professional community that values technique and internal dialogue over broader societal and political relevance. As evidence, they cite data demonstrating a marked decline in the frequency with which articles in top IR journals provide policy prescriptions.

This is neither the whole of their argument nor of their evidence. But it’s an important component—important enough to appear as a figure in both Desch’s 2015 Perspectives on Politics piece and Avey and Desch’s 2020 chapter in Bridging the Theory-Practice Divide in International Relations. Here’s the figure from the book chapter:

My point is pretty simple: whether or not an article self-consciously makes policy prescriptions is a very rough—at best—measure of whether it is policy-relevant.

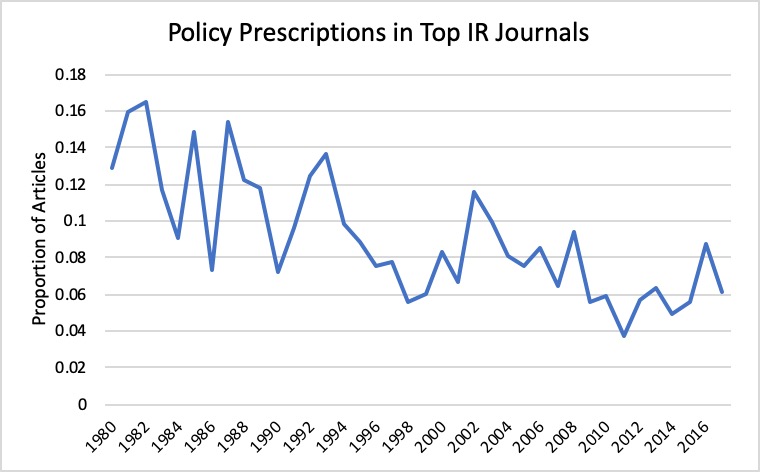

The underlying data on which they base their figure are from the Teaching, Research & International Policy project at the College of William & Mary, whose army of undergraduate RAs hand coded nearly 9,000 articles in 12 top IR outlets from 1980-2017.[1]With five additional years of data, the picture has not changed much, though there does appear to be a slight upward trend since 2011, the low water mark of policy-relevant IR scholarship—at least according to this metric.

Author’s calculations from TRIP data.

There are at least two unstated premises that need to be true for the data to tell the story Avey and Desch want them to tell: 1) policy recommendations in an article are both necessary and sufficient for the article to actually be policy-relevant, and 2) policy-relevant scholarship, rather than policy-relevant scholars, are what is needed to make the discipline of IR policy-relevant. I’ll take them in order.

The first premise is clearly not the case. Explicit policy recommendations are neither necessary nor sufficient for academic work to inform policy debates. Regarding necessity: there is plenty of applied social science that does not make explicit policy recommendations but that nevertheless informs policy.

For example, let’s take scholarship funded by and associated with the Political Instability Task Force (PITF), a group of scholars who produce instability forecasts and advise the US intelligence community. The PITF is funded by the CIA.[2]The forecasting tools the PITF has developed over the years are used by the agency in their stability assessments and planning. Several of these tools have been published and validated by peer review. Mike Ward and Andreas Beger’s “Lessons from Near Real-Time Forecasting of Irregular Leadership Changes” is one such example. According to the TRIP data, it makes no policy recommendations (and indeed, after reading the article, I can confirm that it does not)—even though its raison d’être is to inform planning and policy formation.

An even more famous example is Carmen Reinhardt and Ken Rogoff’s (now discredited) “Growth in a Time of Debt,” perhaps the single most influential piece of macroeconomic research published during the Great Recession—much to the ultimate chagrin of its authors. Unless one construes the following, ultra-anodyne statement as a policy recommendation, the piece is a simple analysis of whether high debt-to-GDP ratios stifle economic growth: “this would suggest that traditional debt management issues should be at the forefront of public policy concerns.”[3]Yet the piece had a profound effect on macroeconomic (specifically, austerity) policy discussions in the United States and European Union. Scholarship can be incredibly policy-relevant and influential whether or not the authors make specific policy recommendations.

Moreover, whether an article makes policy recommendations is, in and of itself, insufficient to demonstrate policy relevance. Most articles—including those that make policy recommendations—are like the proverbial trees falling in the forest with no one there to hear them: they make no sound whatsoever. Relevance requires a combination of topicality and significance. Avey and Desch criticize IR scholarship for lacking the former (i.e., focusing on arcane topics), but I’d argue the deeper issue is with the latter: the tiny, specialized readership most articles attract. The dominant format of an IR article—10,000+ words, jargon-filled, more heavily caveated than a Hollywood prenup, and typically in writing and peer review for years—is simply not amenable to consumption and application by policy audiences. This is especially true of those at the highest level of influence (Secretaries and Undersecretaries of State, Defense, etc.) with whom Avey and Desch are particularly concerned. I’m skeptical you’d find Wilbur Ross thumbing through International Organization if only it had fewer regressions.

The second premise, that practitioners are clamoring for policy-relevant scholarship, is also not the case—at least in my experience. I have found that policy and practitioner audiences are interested in academic expertise, not academic scholarship, per se. In my briefings and writings for practitioner audiences, I am almost never asked about my scholarship. I am usually asked questions about either very narrow subjects—subjects so narrow or time-sensitive it is nearly impossible to envision someone writing (at least academically) on them—or broader-aperture themes. In either event, I’m being asked to weigh in on the basis of my accumulated expertise as evinced by my scholarship in a particular area, rather than specific policy recommendations that follow logically or necessarily from some analysis I’ve done. They want engagement with academics—which is different from engagement with scholarship quascholarship—and, as I’ve argued elsewhere, a lot harder to quantify, encourage, and reward.

I share Desch and Avey’s commitment to making scholarship more useful to society at-large, and to mentoring early-career scholars in how to engage responsibly with practitioner audiences. But I disagree that what is needed is for more scholars to embed explicit recommendations in their published work—at least their peer-reviewed work in top disciplinary outlets. We need to invest time in translating our own work via policy briefs, blog posts, and in-person meetings with practitioners. Our path to broader relevance and the public good does not, in the main, pass through the concluding sections of our peer reviewed manuscripts.

Note: Big thanks to Steve Saideman, Mike Tierney, and Julia Macdonald for comments on this post.

[1]“Top” outlets: American Journal of Political Science, American Political Science Review, British Journal of Political Science, European Journal of International Relations, International Organization, International Security, International Studies Quarterly, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Journal of Politics, Journal of Peace Research, Security Studies, andWorld Politics.

[2]Note: I am a member of the Task Force.

[3]Per TRIPS coding rules: “Does the author make explicit policy prescriptions in the article? We only record a value of “yes” if the article explicitly aims its prescriptions at policymakers. In the case that the author prescribes policy options it does not have to limited solely to members of governments. Prescriptions can be recommended to members of governments as well as IGOs, NGOs, etc… in order to fulfill the requirements for this variable. A prescription for further research on some topic does not qualify, but a prescription that the government ought to change its foreign policy or increase funding for certain types of research does qualify. The fact that a model has implications that are relevant for policy makers does not count as a policy prescription. A throwaway line in the conclusion does not qualify as a policy prescription.”

Cullen Hendrix is Professor and Director of the Sié Chéou-Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy at the Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, and Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. His current projects explore conflict and cooperation around natural resources and the ethics of policy engagement by academic researchers.

0 Comments