This is a guest post from Alexander R Arifianto (Twitter: @DrAlexArifianto), a Research Fellow with S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His research focuses on contemporary domestic politics and political Islam in Indonesia.

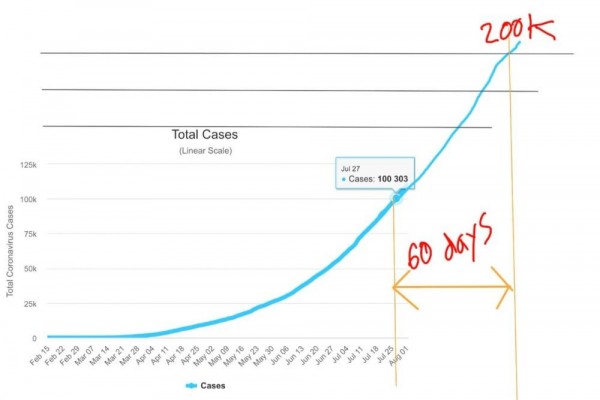

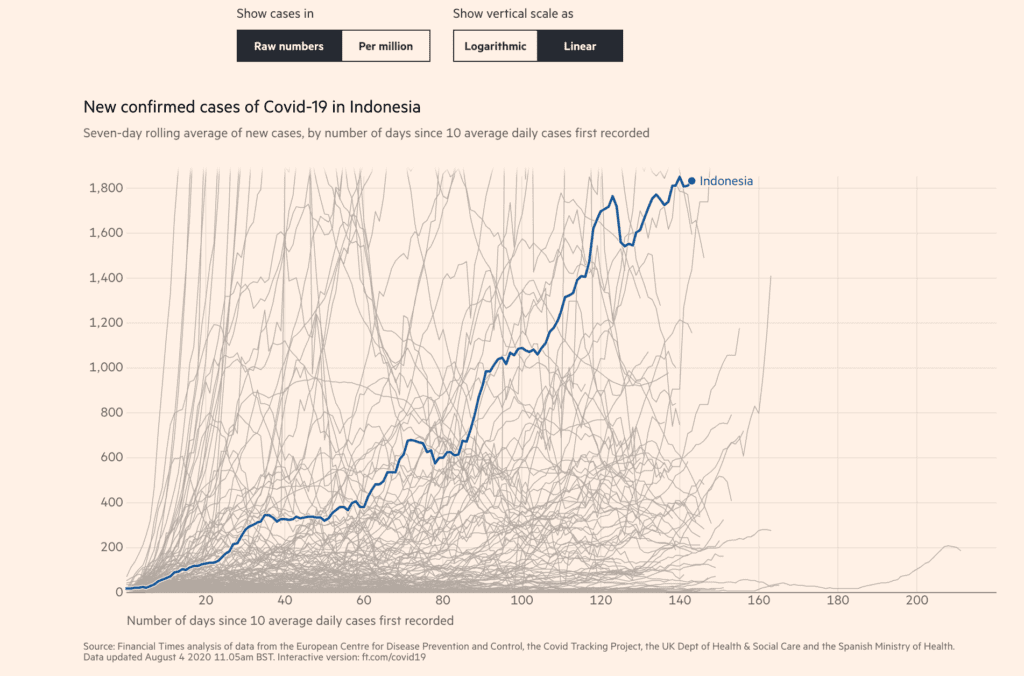

Nearly six months after the first case of coronavirus was first diagnosed in Indonesia, the country is in the midst of its largest public health crisis in history. As of August 3rd, about 113,000 Indonesians are confirmed to be infected and 5,300 have died from the illness. Indonesia is currently ranked the 23rd country with the most COVID-19 cases worldwide. A model developed by Sulfikar Amir, a sociologist based at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, predicts COVID-19 cases in Indonesia will reach 200,000 cases over the next two months.

Indonesia’s 270 million population marks it as is the fourth largest country in the world measured by population size. It is also the largest Muslim-majority country and the world’s third largest democracy. Lastly, it is the largest economy in Southeast Asia and is widely considered as a rising middle power in Asia. In a region where most countries have managed to mitigate the pandemic – with varying success rates – Indonesia’s failure to effectively contain the virus is puzzling to international observers.

In this post, I argue that Indonesia’s lackadaisical and half-hearted pandemic response has its roots in its pre-existing historical legacy that affects how Indonesian policymakers formulate their COVID-19 mitigation policy. These include an incompetent yet insulated bureaucracy that does not value policy advice from external experts and a power-sharing arrangement among members of its political elite that emphasizes short-term political calculations over taking coherent, coordinated, and decisive actions.

A Weak Civil Service

Indonesia has been a democratic state since 1998, after enduring 32 years of authoritarian rule under General Suharto. Under his reign, Indonesia was a very centralized state, where the national government ran and controlled everything, but political power was highly personalized around Suharto, his family, and business cronies. The end result was a bureaucracy that was highly insulated from the public, yet was very corrupt, patronage driven, and fully subservient to the executive. These features of the Indonesian bureaucracy persist to this day.

Given Suharto’s priorities to create stable fiscal and monetary policies and to invest in large infrastructure projects to foster economic development, the Finance and Public Works ministries became key ministries which employed more technocratic civil servants and received more funding from the state budget. Other ministries like the Ministry of Health were less meritocratic, had less technocratic staff, and received far less state appropriations. Indonesia’s public health spending over the past two decades was stagnant, averaging just 2.6 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which means the Health Ministry has serious difficulties combating infectious diseases like dengue and malaria, let alone the novel coronavirus.

While the May 1998 ‘Reform’ (Reformasi) protests successfully ousted Suharto from power, it left much of the state institutions, including the bureaucracy and the security sector (military and national police) intact. Even today, most of Indonesia’s senior civil servants and security officials are driven from the ranks of officers who began their careers during Suharto’s final decade in office. A culture of ‘father-ism’ (bapakisme) has been perpetuated within the civil service, where senior bureaucrats defer to the policy decisions from the president and his ministers and implement them without asking any questions – no matter how good or bad these policies are.

Inter-Elite Power-sharing

Another historical legacy that has hampered Indonesia’s management of COVID-19 pandemic is the inter-elite power sharing arrangement implemented by each post-Suharto Indonesian president, including by Joko Widodo (also known as Jokowi), Indonesia’s current president.

This practice, called by Dan Slater and Erica Simmons as “promiscuous power-sharing,” is an informal inter-elite bargaining in Indonesian politics, that began since the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998 as a way for ruling governments to compensate ‘losers’ to minimize potential opposition or dissent in the parliament. This arrangement is deeply embedded in post-Suharto Indonesian politics. Every president elected since 1998 has used it to coopt their opposition rivals, resulting in ‘rainbow’ coalition arrangements where most parties sitting in the parliament, were accommodated by each regime with cabinet seats.

Widodo’s presidency continues this power-sharing practice. Despite a deeply polarized re-election campaign last year, Widodo managed to strike a deal with his former presidential opponent Prabowo Subianto, who was appointed Indonesia’s Defense Minister, despite huge public backlash against his alleged human rights abuses when Subianto was an army general serving under Suharto, his former father-in-law.

In fact, Widodo managed to include all but three small parties sitting in the current parliament to be represented in his new cabinet. The cabinet line-up was largely constructed as a payoff to the different parties and business tycoons who had supported his re-election campaign.

In addition, at least five cabinet positions were given to retired officers of the Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI), again as payoff to officers who are considered to have ‘secured’ Jokowi’s re-election. Among these retired officers were Terawan Agus Putranto, the Minister of Health – a former general who once headed the TNI’s largest hospital in Jakarta. He was appointed despite the objection of the Indonesian Medical Association due to his promotion of an unproven medical procedure to treat stroke patients.

The end result of “promiscuous power-sharing” arrangement, especially under Widodo’s presidency, is the domination of Indonesia’s political elites – political parties, prominent businessmen, and current and retired TNI officers – inside the cabinet. Only a small number of ministries are run by ministers with technocratic expertise.

Inept Bureaucratic Response

Indonesia wasted an entire month of February 2020 preoccupied by public statements by its political elite who downplayed the potential dangers of the coronavirus outright instead of preparing the country for the pandemic. The government also failed to increase its public health spending to provide front-line medical workers with resources such as medical and personal protective equipment (PPE) to prepare themselves for the pandemic.

Putranto – the country’s health minister – was widely quoted in the media declaring God had protected Indonesia from the virus because he listened to its people’s prayers. Other ministers and politicians also downplayed the virus significance. Luhut Pandjaitan, one of Jokowi’s senior ministers and closest confidantes, believes that Indonesia’s tropical climate would prevent coronavirus from spreading, an assertion that has proven false as cases in Indonesia have steadily increased throughout summer 2020s.

Indonesia was fully unprepared when the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed in March 2020. Since then, the pandemic has extracted high casualty rates among Indonesians. Since Indonesia has one of the lowest COVID-19 testing rates in the world, many believed the actual infection and death rates are much higher than what is officially reported by the government. Data from burial rates using COVID-19 protocols indicate the number of deaths could be up to three times the official rates.

Medical professionals paid a heavy price in Indonesia’s struggle against the pandemic, with 72 medical doctors confirmed dead so far from the deadly virus. Despite this, the Health Ministry had spent very few of the allocated state funds budgeted as part of the government’s emergency COVID-19 budget, leaving hospitals short of protective equipment, medicine, and other necessities to enable medical staffs to treat pandemic victims more effectively.

This indicates that the Ministry of Health is lacking the capacity to properly deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. The low level of public health spending and leadership of a minister who is known to make controversial statements downplaying the pandemic do not instill much confidence in the ministry’s ability to effectively manage the country’s worst public health crisis.

Ministerial Rivalries

Meanwhile, President Widodo faces growing criticisms that he has not taken the pandemic seriously and has failed to discipline and coordinate with his ministers which often issued contradicting strategies on how to best handle the pandemic. One of the Indonesian president’s main duties is to promote coordination and cooperation among ministers. However, Widodo often takes a ‘hands-off’ approach, preferring to delegate such tasks to senior ministers like Pandjaitan, who was seen by observers to have intervened to prevent ministries and local governments from adopting more stringent pandemic mitigation measures.

As a result, members of the government’s COVID-19 mitigation team are now competing with each other to issue pandemic mitigation policies and remedies that have no scientific support whatsoever. For instance, on May 12, General Doni Monardo, chairman of Indonesia’s COVID-19 Mitigation Task Force, declared that all workers under the age of 45 years old in essential sectors, including in broadly defined “strategic industries,” would be allowed to resume normal work. Public health experts immediately criticized the policy as an implicit endorsement of a “herd immunity” strategy, forcing the government to backtrack from it.

More recently, Syahrul Yasin Limpo, Indonesia’s Agriculture Minister, announced his ministry has developed and mass-produced an eucalyptus necklace which he claimed would have prevented COVID-19 transmissions. This initiative was developed without any scientific evidence that eucalyptus would have any effect on the virus. Limpo’s initiative motivated other Indonesian politicians to promote their own COVID-19 remedies – again without any scientific proof that any of them would have cured the virus.

The ongoing competition between different ministries to produce alleged COVID-19 cures – and the lack of monitoring and coordination – illustrates the impact of Indonesia’s “promiscuous power-sharing” arrangement on the country’s inability to produce a cohesive pandemic mitigation strategy. Having so many political parties and personalities in a “rainbow coalition” cabinet means that ministries often become fiefdoms for a particular political party or a politician with strong personalities, who then proceeded to issue their own policies with no coordination with the president and other ministers.

The missing voice from all these intra-ministerial infighting is sound advice from scientists and public health specialists. Their inputs are almost not being heard in the government’s half-hearted and uncoordinated responses to the pandemic. This is because of a climate of hostility among senior politicians and policymakers against scientific advice, which are often critical against the government’s pandemic mitigation policies. The “father-ism” culture among Indonesian political elite also reinforces hostility toward scientists. Politicians and senior bureaucrats perceive themselves as ultimate decisionmakers who set policy for all Indonesians to follow, not scientists who largely come outside of their inner sanctum. Disaffected by the government’s lack of cooperation and transparency, several Indonesian scientists have partnered with civil society activists to develop independent COVID-19 monitoring websites such as KawalCOVID19 and LaporCovid-19. Both websites collect case data independently from the government, relying on self-reported data sent directly by citizens through applications that are downloadable from these websites.

Lessons Learned

Indonesia’s poor results in its COVID-19 mitigation policy so far is attributable to several factors, including: lack of strong leadership from its president and key ministries in charge of the pandemic mitigation (particularly its Ministry of Health), lack of capacity within key ministries to rapidly disburse state funds and other necessities to frontline personnel, infighting among ministries and senior politicians that resulted in lack of coordinated response, and a culture of hostility among its political elite against seeking advice from the country’s scientists and public health specialists.

This post has argued that all of these factors are rooted in the historical legacies within the Indonesian political elite and civil service, including an insulated policymaking environment that place these elite to be superior from ordinary Indonesians, a weak civil service that is struggling to design and implement effective policy – particularly in public health, and the informal “promiscuous power-sharing” arrangement that divides cabinet positions among all key political elites, yet also promotes infighting and lack of coordination among them.

Altogether, they create an environment that explain the half-hearted response of the Indonesian government in its COVID-19 mitigation. It has resulted in thousands more infections and deaths that could have been averted had the government followed the lead of its neighbors to implement stringent public health policies from the time the pandemic reached its shore six months ago.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks