How do colleges and universities go about hiring tenure-line (or the equivalent) faculty in politics and international relations? Back in 2013, I provided a short overview of the typical U.S. process:

- Starting in the late summer, political-science departments post position announcements with the American Political Science Association. Most job hunters read those announcements on e-jobs and decide whether or not to apply.

- Prospective hires send in materials to institutions. These typically include: (1) at least one writing sample — sometimes a published article, sometimes an article-in-process, and sometimes dissertation or book materials; (2) three letters of recommendation; (3) an application letter detailing why the committee should hire you; (4) a curriculum vitae [CV]; and sometimes (5) a graduate transcript. Some institutions will also ask for an undergraduate transcript, and some will only ask for contacts should they seek letters of recommendation.

- Committees, often composed of 3-5 faculty members, read [the meaning of “read” may vary] those applications and winnow the field down. They may produce a “long short list” of, typically, 6-10 candidates who they are interested in. They may jump directly to the “short list” of, in general, 3-5 candidates who they want to bring in for interviews. Some kind of oversight may or may not follow. Prospective Interviewees are contacted and asked to visit campus.

- The campus visit takes place over 1-2 days. The candidate meets with various faculty, administrators, and graduate students. Meals, including a dinner, take place. Candidate gives ~45 minute job talk with a question-and-answer period.

I added that:

At liberal arts colleges, of course, (1) the meeting with graduate students is replaced by (often multiple) meetings with undergraduates and (2) the research presentation is either supplemented or substituted with a teaching presentation to undergraduates. Telecommunications interviews may occur at any stage of the winnowing process. Some schools also conduct interviews at APSA. I don’t know much about the two-year college process. Otherwise, YMMV.

In retrospect, I probably should have included more on other systems, especially how British universities conduct on-campus interviews. I’ve interviewed for two senior positions in the UK. I had trouble adapting to the shorter job talks and the committee interview, but I really enjoyed having dinner with the other candidates. I imagine that’s a lot more stressful if you don’t already have a job.

Anyway, it’s been nine years since I wrote that post, and there have been only minor changes to how U.S. departments hire faculty.

There are more options for finding job listings. The pandemic pushed the on-campus portion online; some schools still aren’t doing on-campus interviews. I get the sense that committees are more inclined to conduct short interviews online with applicants on their “long-short” list.

What happens once the interviews are complete is still the same. If all goes well, the committee ranks the candidates and – after securing approval from the administration and relevant units – makes an offer to their first choice. If that person declines, they move down their list until they hire someone.

It sometimes doesn’t go that well. The committee, or at least a majority of the committee, often decides that they don’t want to hire at least one of the candidates. Sometimes a majority doesn’t consider any of the candidates “above the bar” and declines to make an offer.

Given that academic jobs can easily generate over a hundred applicants, you might think the committee would just interview more candidates. That rarely happens. In most cases, the search “fails” and, assuming the administration doesn’t reclaim the line, the unit searches again the following year.

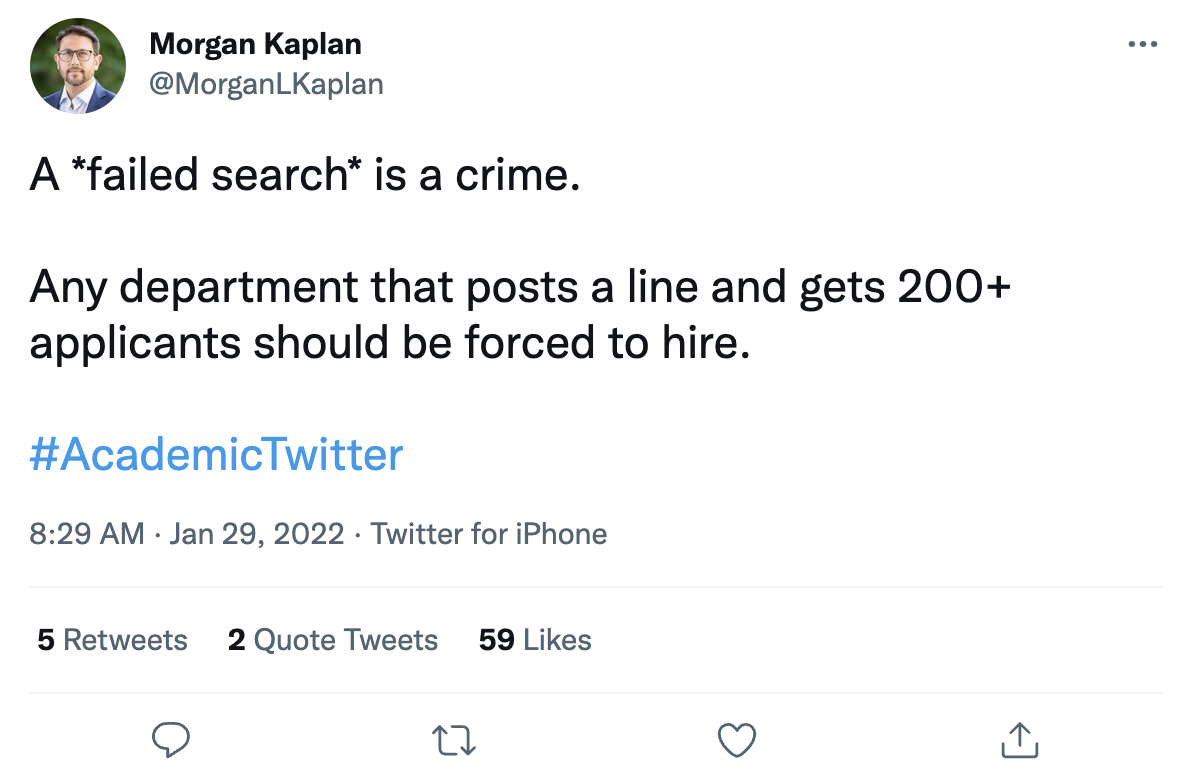

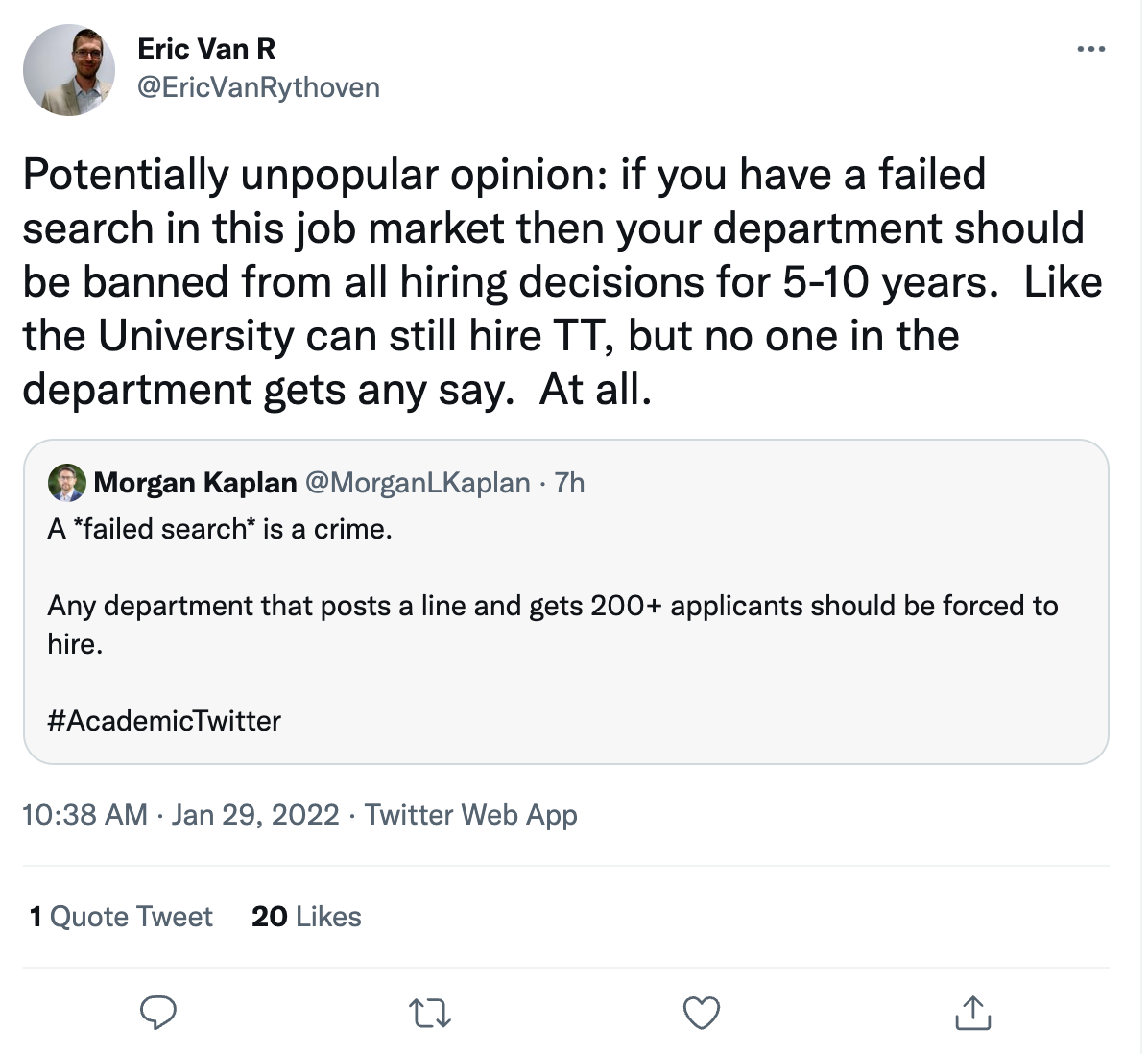

Over on the Twitters, there’s been some discussion of the “failed search.”

Most interlocutors seem to agree.

But, as others point out, that’s not always an option. Some positions, perhaps due to donor requirements, have very specific requirements that not very candidates can meet.

There are other reasons. Alex Barder notes that “Often times a failed search is a consequence of administrative machinations than the failure of a department.” Jennifer Mustapha writes that, after having been on the hiring side for a while, “I do actually see how easily a “failed” search could happen & through no fault of the dept, necessarily.”

Indeed, a search can “fail” because the committee becomes deadlocked. Bringing in more candidates might solve the deadlock in some circumstances, but not always, especially if strong disagreements render the committee dysfunctional. Responsible parties may conclude that pushing ahead with the search is going to do more damage than kicking the can into the next year.

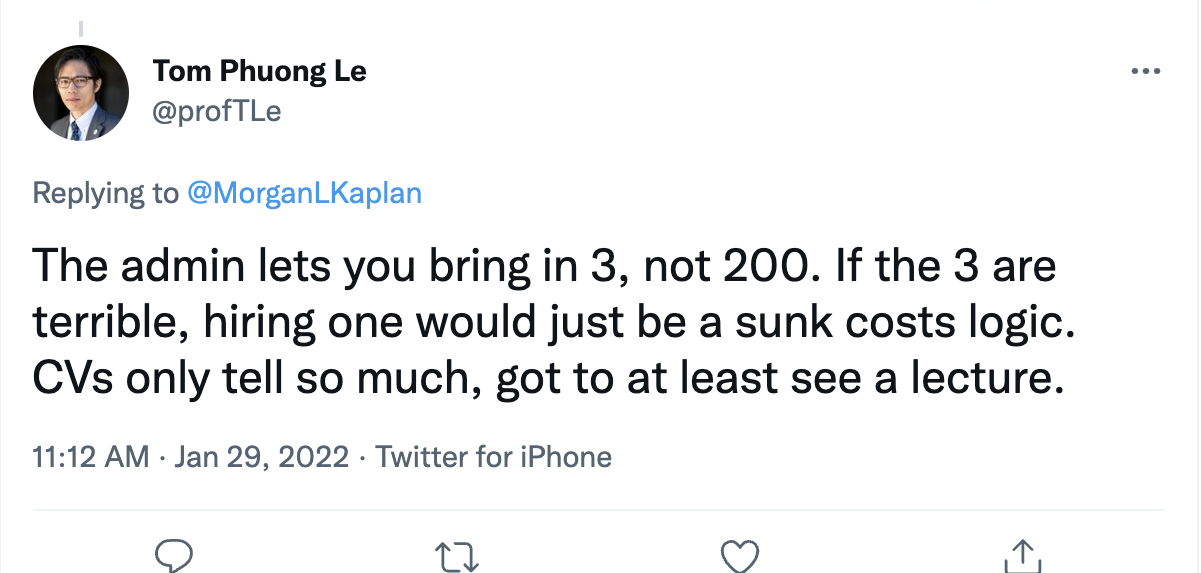

There are also resource constraints. As Tom Phuong Le points out:

Le’s right that administrators may not allow more interviews, and that the department may not have the option to bring in more candidates. Among other things, on-campus interviews cost money.

“But wait,” you might ask, “if departments are already substituting online for on-campus interviews, doesn’t that solve the problem?”

And I would respond, “That’s an excellent point. I’m not saying that I’ve tried to make this argument to colleagues. I’m also not saying that I haven’t.”

What are the main objections?

- Many faculty are reluctant to invest the time it would take to interview more candidates, whether initially or in a second wave.

- The rest of the faculty may not be great about attending job talks, and increasing the number of candidates might make things worse.

- A committee that interviews more candidates will take longer to make offers, which means they may lose their candidates to schools that interviewed fewer people.

It’s true that academic hiring is a bigger deal than in a lot of other sectors; there’s a good chance the person that gets hired will be in that job for decades. But does that really mean faculty can’t put in the additional effort to interview at least a few more candidates? It’s obviously not great if faculty aren’t attending job talks, but that’s not a reason to make the job market less efficient.

There are implicit assumptions running through some of these objections.

One is that the short list represents the “best” applicants in the pool. That strikes me as overly optimistic. Especially when it comes to junior candidates, there’s just not enough information in an application packet to make a confident judgment about future performance.

Another is that there aren’t more than a handful of people in the pool who are “good enough” for a department to hire. I find this hard to believe and, outside of same very narrow searches, it certainly isn’t my experience. There are always more than a handful of applicants who could prove to be worth hiring. If the committee doesn’t think that’s true, then maybe there’s something wrong with their standards.

So, yes, departments should take advantage of technology to expand the number of candidates they interview; and yes, they should be more willing to revisit the applicant pool.

In my experience (in a different discipline, but one with the same basic process), many failed searches result when the department and college’s top candidate turns the position down in favor of a position somewhere else. The process of reaching the decision about which offer that top candidate will take, moreover, can take weeks or even months (something I experienced personally, once — a search that didn’t ‘fail’ until October). This is especially true if two relatively high-profile institutions are trying to land the same candidate, and have deans willing to up the ante repeatedly. By the time the first candidate is lost, then, the second and third who came to campus may have already accepted other offers, too, or may simply lack broad enough support in the department involved (having been ‘not the best’, after all). Departments are stiff-necked and prideful, and so are administrators, and the temptation to pull the plug and try again gets stronger as the beginning of the next cycle looms.