The ongoing war in Gaza has stretched on for over two months after the horrific October 7 attack by Hamas against Israel, which resulted in Hamas killing over 1000 Israelis and kidnapping over 200. Israel’s subsequent airstrikes and ground invasion have killed over 10,000 Palestinians (with the Hamas-run Gaza Health Authority report numbers approaching 20,000). With the war now drawing close to Christmas, some are paying attention to the status and responses of Palestinian Christians.

Christians make up a small minority of Palestinians, with only about 1,000 in the Gaza Strip and about 47,000 in the West Bank. Despite their small numbers, they are an important part of worldwide Christianity due to the proximity to sites associated with Jesus Christ. Many Palestinian Christian sites, such as Bethlehem–the traditional birthplace of Jesus–are also popular tourist destinations.

But not this year. Due to the ongoing war in Gaza, many Palestinian Christians are canceling or muting Christmas celebrations, while tourists are mostly absent.

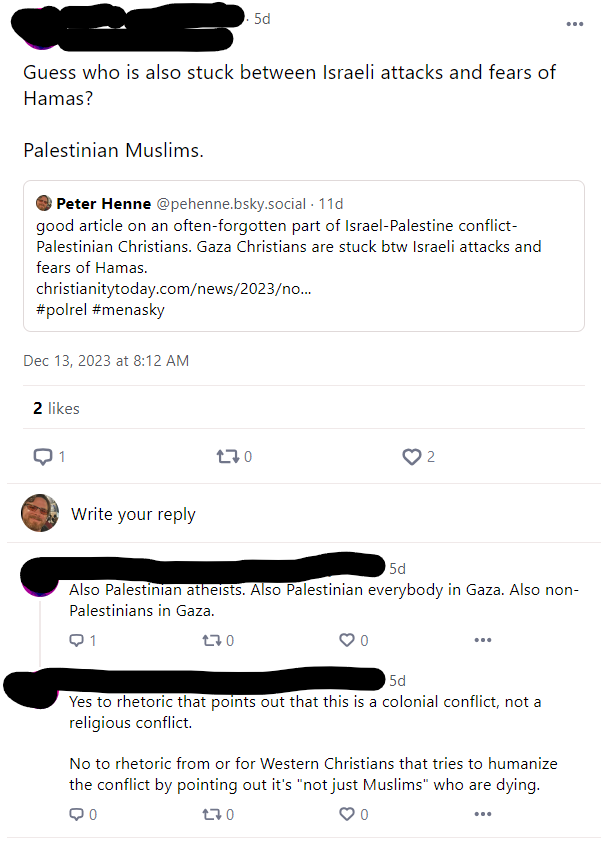

I had noted the struggle of Gaza’s Christians a few weeks ago on BlueSky. I got a few likes, a satisfactory amount of engagement considering I’m still new on the site. But one response caught me a little off guard (although in retrospect I should have expected it).

The person seemed to be suggesting attention to Palestinian Christians means I don’t care for Palestinian Muslims, and I’m somehow colonialist. This was just one random person, to be fair. But it is an attitude I’ve encountered before, that there is something suspect in expressing concern about Christians struggling with persecution and conflict. It’s worth exploring that.

What Christians are experiencing around the world

It may sound strange to think of Christian persecution for many in the West, considering Christianity has been the dominant religion for hundreds of years in the Americas and almost two thousand years in Europe. Even the strength of Islam under the Ottoman Empire and earlier caliphates never really threatened all of Europe. But Christians do face problems around the world.

Palestinian Christians have faced pressure from both fellow Palestinians and Israel. The Palestinian Bible Society was bombed shortly after Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip in 2006; Hamas denied connection, but the culprit was never discovered. Meanwhile, many Palestinian Christians have left the region due to Israel’s actions; this includes restrictions on the number of Christians who can celebrate Easter at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

Other Middle Eastern Christians have suffered. Egypt’s Coptic Christians have been the targets of ISIS attacks during both Christmas and Holy Week. ISIS also committed atrocities against Iraqi and Syrian Christians, which pushed these communities to the brink of extinction.

Many were worried concerns for Christian persecution were a cover for far-right identity politics before Trump, and that concern has only grown.

Christians have been targeted elsewhere. This summer, ISIS attacked a Christian school in Uganda, killing 42. Suicide bombers attacked Indonesian churches in 2018, while earlier attacks against churches during Christmas in that country. 2019 Easter bombings in Sri Lanka killed over 200. And an attack on an Advent mass in the Philippines a few weeks ago killed four and injured over 50.

We are still a week away from Western Christmas, and a few weeks away from Orthodox Christmas, so expect more attacks to occur.

It’s easy to come up with non-religious explanations for this violence. Schools are easy targets. ISIS wanted to terrorize populations into submission. Military activities in the Philippines have angered militants. These all may be valid (although I find it frustrating we are so quick to discount religion when it’s an obvious factor in targeting and mobilization). But they’re hardly comforting to the victims of these attacks and broader persecution.

Why people are wary of focusing on this

Yet, people are wary of dwelling on these incidents too much. That random person on Bluesky wasn’t that much of an outlier.

Some of this comes from something implicit in my critic’s posts. To many, Christianity is a Western religion, and the religion of the oppressor. So any concern for Christians is a concern for oppressors, or at the least recent and inauthentic transplants into non-Western societies.

Others have more substantive arguments.

Some worry that emphasizing the religious dimensions of conflict can exacerbate tensions, and maybe even increase the extent to which Christians are targeted. I, for example, pushed back on Trump Administration plans to direct aid exclusively to Middle East Christians for this reason in a report for the Center for American Progress.

Others worry a focus on Christian persecution simplifies complex problems. This was some of the critique of the Trump Administration’s pressure on Nigeria over attacks on Christians there. Trump reportedly asked President Muhammadu Buhari “why are you killing Christians?” when they met. Buhari said he tried to explain it was not a religious conflict. Indeed, Christian-Muslim tensions in Nigeria also involve overlapping ethnic and economic divisions. So reducing it to Christian persecution may be counterproductive.

Any concern for Christian persecution needs to be concern for the society in which they suffer.

The final pushback has to do with a name that keeps coming up here: Donald Trump. As I’ve discussed on this site, international religious freedom became a priority for the Trump Administration, thanks to Mike Pence’s evangelical outreach. Yet, it took on a sectarian and hypocritical tone, with a focus on Christian persecution alongside rhetoric and policies directed at Muslims and a soft stance on authoritarian states friendly to Trump.

The connection between defense of Christians and conservative causes extends beyond Trump. The Religious Freedom Institute, which has helped persecuted Christians in China, has also defended US doctors who refuse to use their patients’ preferred pronouns (full disclosure, I worked with many of its leadership when they were at Georgetown’s Berkley Center). Meanwhile, some groups advocating for persecuted Christians have cheered authoritarian leaders like Hungary’s Viktor Orban for his supposed defense of Christianity. According to a 2017 PRRI survey, 57% of white evangelical Christians believe Christians are discriminated against in the United States (as someone who used to track incidents of religious repression and violence around the world, I always find it difficult to bite my tongue when conservative US Christians claim they are persecuted).

Many were worried concerns for Christian persecution were a cover for far-right identity politics before Trump, and that concern has only grown.

So when can we talk about Christian persecution, if at all?

Time for more disclosure–I am a practicing Christian, raised Lutheran and now Episcopalian. I know some conservative Christians may actually question my faith given those details (if you aren’t privy to intra-Christian fights, count yourself lucky), but it is important to me. So I am trying to balance my own personal identity with my scholarly pursuits.

First, some have gone beyond pointing out Christian persecution to saying Christians are the most persecuted group around the world. This is wrong.

When I was at Pew, our data showed Christians persecuted in more countries than any other religious group. But that was a simple dichotomous measure of harassment, and didn’t account for population size. People still tried to use that to argue Christians had it the worst (I never liked that figure to begin with, but wasn’t able to drop it). I’m not sure who would be the most persecuted once we account for intensity and population, but I suspect it would be Jewish people.

Even if Christians were the most persecuted, it wouldn’t matter. It’s not a contest. Indeed, the whole point of the religious freedom community was to move beyond narrow sectarian concerns.

Second, and at the same time, it is also wrong to claim attention to Christian suffering is problematic.

I think there is legitimate debate over whether states should be allowed to limit Christian missionaries (although personally I’ve found that any state control over religion is bad for everyone). But many of the Christian communities I’ve discussed here predate Western imperialism and, in the case of Palestinians, played a crucial role in Arab politics and society. Even when Christian communities arose through colonial-era missionaries, they still have a right to exist in peace.

Finally, small Christian communities can play an important role in many conflicts. As I discussed in my aforementioned CAP report, Iraqi Christians can serve as a bridge between larger communities, limiting tensions. They can also expand Western understanding of the complexities of their societies. In 2014, Ted Cruz spoke to a gathering of Middle East Christians and gave a speech that was basically praise for Israel. He got booed off the stage. While many conservative US Christians strongly back Israel, that is not a feeling shared by Middle Eastern Christians. This event may have helped some in the United States realize that (and was actually part of my intent with my Bluesky post).

Clearly, I think Christians are suffering, and we should care about that. As I pointed out to my Bluesky critic, it’s actually kind of Orientalist to assume any attention to Middle East Christians is inauthentic, as you’re imposing your own Western (albeit lefty) lens and erasing this important part of Middle Eastern society. But we (either Christian activists or observers in general) should not try to claim they suffer more than other groups. We also shouldn’t only pay attention when Christians are affected. And we definitely should not make their suffering a way to advance our own political goals.

Bottom line, any concern for Christian persecution needs to be concern for the society in which they suffer.

UPDATE: Edited to fix style issue.

0 Comments