If international relations as a field is to have a just purpose—not just justifying the power-hoarding and power-wielding of a ruling class—it needs more concepts to critique power, relate policy to peaceful ends, and surface rather than shroud the price that others pay for what our states do in the world.

Most IR scholars imagine ourselves toiling on behalf of the greater good.

But if the policy implications of our work rationalizes more guns and bombs, more death, more inequality, more erasure of marginalized and oppressed people, at a certain point we have to question which side of the cosmic balance we’re actually on. Insofar as politics is ultimately about power, the study of it must do more than simply rationalize antagonistic forms of using it to secure some at the expense of others.

What about the scientific purist? You can produce the most methodologically sophisticated work, demur at normative claims in favor of a vision that you’re just producing knowledge. There’s a place for that in the universe. But who benefits from it, and who might be harmed by it? That scientific method does not respect morality makes it all the more vital that the scientist does.

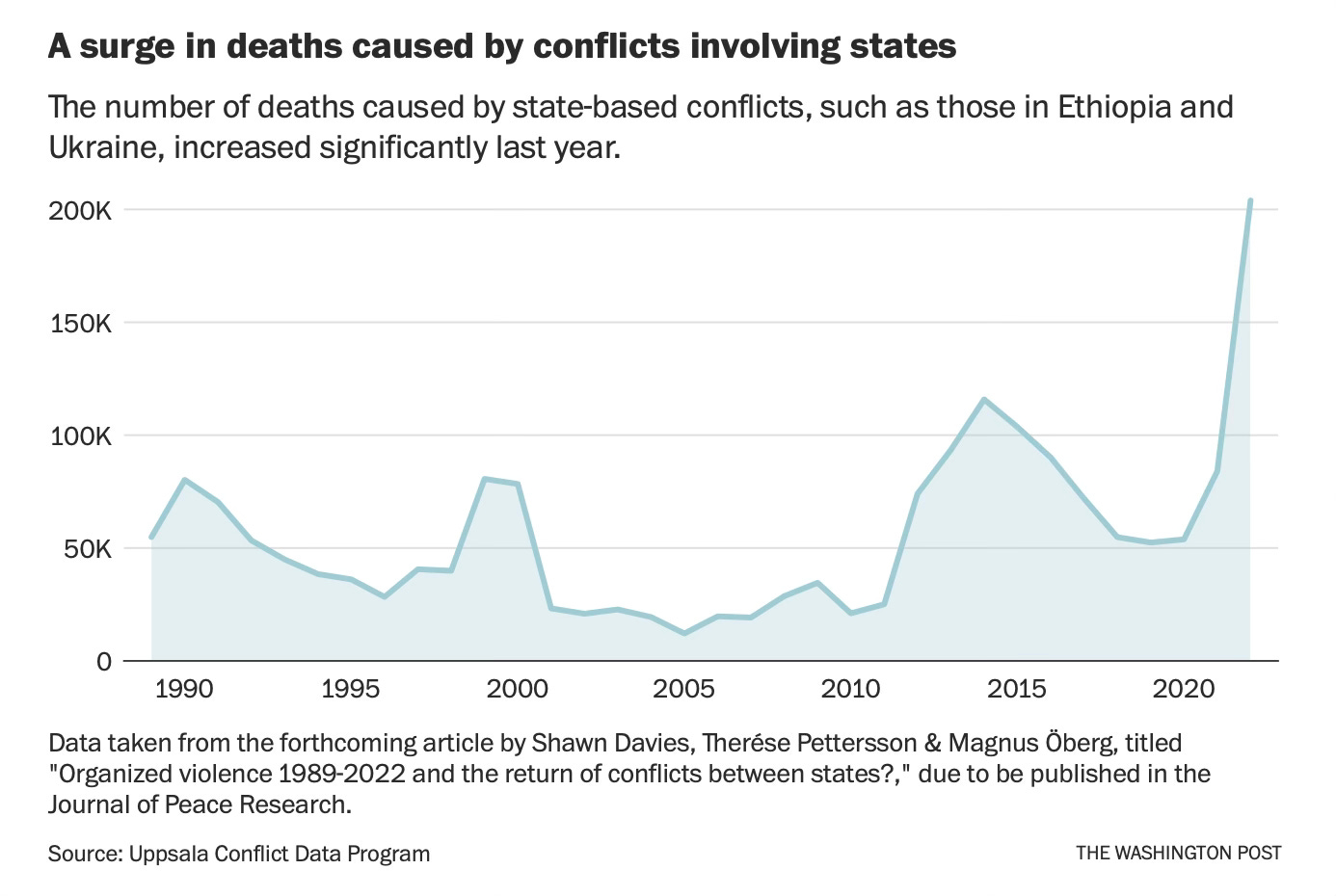

And of course, at a macro level, I’m not sure the world has ever had more IR scholars toiling away than it has the past 40 years. Still, we are here:

I’m not putting the rising body counts at the feet of IR scholars. Correlation is not causation, after all. And blaming IR scholars for a tragic trend in rising militarized violence would distract from those who actually have power. For better or for worse, IR scholars are not powerful.

But it’s hard to look at the big picture and say that we as a planet are on the right track—those of us who study planetary power relations owe our fellow humans some introspection. Something must be done, and one small thing with great promise is to recover the radical ambition of the peace intellectuals who were once major voices in our discipline. We ought to be intellectually discontented.

To that end, few peace intellectuals were more ambitious than Johan Galtung. I got word that Galtung died last week while I was visiting Auckland and the Bay of Islands. The Peace Research Institute Oslo published this statement, which read in part:

After establishing what would become the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) in 1959, he went on to found the Journal of Peace Research in 1964…Galtung’s first projects at the Peace Research Institute resulted in a series of articles in the Journal of Peace Research.These articles continue to be his most cited works and concerned varied and important topics such as structural violence, concepts of peace, international news dissemination, imperialism, and the role of summits in international relations. Together with Arne Næss, he was also a pioneer of efforts to codify Gandhi’s ideas about non-violence and conflict management…After Galtung left PRIO and moved to the University of Oslo and later to his international career, he also reoriented himself in many ways in a purely scholarly manner. His public remarks also became more acerbic and polemical, gaining him many critics.

Galtung’s output is too wide-ranging for me to try to summarize it, and I don’t want to suggest he was right about everything. In a 1988 debate with peace-scholar Seymour Melman, the two clashed swords—sharply—about what needed to be done to realize peace (I’ve been intending to write more about that debate because it’s fascinating).

But Galtung came up with many generative ideas that aided others’ ability to critique power and make our states more accountable to the common good. For example, Galtung’s concept of structural violence, and the corresponding distinction between negative v. positive peace, has been crucial in my last two books. I still teach it in my Intro to Security Studies course.

The concept of structural violence is an important construct for more accurate thinking about the costs and benefits of not only foreign policy but public policy generally. It’s an analytical building block for critiquing power on behalf of meaningful security.

We need more of that. The peace-oriented, antimilitarist repertoire is still largely working off of ideas generated in Galtung’s day. And while the man deserves his flowers, I can hardly think of a better way to honor his legacy than to devise tools and analyses with the verve and independence of mind that he did.

Cross-posted at the Un-Diplomatic Newsletter.

0 Comments