“A specter is haunting strategic studies—the specter of peace.” These bizarre words are from Richard Betts, who provocatively presented peace itself as a problem in a largely forgotten article from 1997 asking, “Should Strategic Studies Survive?”

Betts answered his title question in the affirmative. As one of the most prominent scholars that strategic studies has ever produced, it’s unsurprising Betts would come to the field’s defense. It’s more surprising, though, considering that Betts has a long record warning about the limits of the use of force and expressing skepticism about the possibilities of strategy generally.

But Betts also offered a revealing confession (and massive understatement) in his plea to preserve strategic studies that illustrates the problem with keeping the field as it has always been: “For whatever reason, the United States finds itself in a war or crisis in almost every generation.”

Violence: From Unrealistic Obsession to Cause of Incuriosity

Strategic studies is the most violence-centered sub-field of international relations. Since its origins in the early Cold War, it has been consumed by questions of military force. For many strategic theorists, force is literally what it’s about. That confined gaze has not only impaired strategists’ ability to see beyond proximate causes of security problems to the issues at their root; it has also straightjacketed the means by which to address security problems. The tools of the national security state are, in most cases, antithetical to peace, yet the only tools of relevance in strategic theory.

Betts’s shrug that, “for whatever reason,” the United States constantly finds itself in war affirms what I’m saying. If you do not look past proximate causes, then conflicts really do just exist “for whatever reason.” What’s in front of you is all that matters.

If this is how you think, then history’s only salience for you is whether it can help you fashion more efficient military means to achieve political ends. Strategic studies, in other words, encourages an incuriosity about the historical circumstances that create the problems that occupy it even though it also celebrates selective dead men of history (Clausewitz etc).

Violence as a Self-Licking Ice Cream Cone

The way national security strategists are trained to think about their task is self-perpetuating rather than self-abnegating. And so, as Hedley Bull once acknowledged:

No doubt strategists are inclined to think too readily in terms of military solutions to the problems of foreign policy and to lose sight of the other instruments that are available.

This is one of many problems that strategic studies must correct for if it is going to continue to exist.

If strategic studies had a different raison d’être, that is, if it was less about advising the best means of militarized violence and more about constructing systems that foreclose on the prospect of violence, then strategic studies could exist forever and ever as a public good. But if it’s just about how the state can give the smoke to its enemies, then the goal really does need to be the demise of the field of study itself.

Making Violence Obey Reason Does Not Make It Good

Finally, if scholars or governments think strategic studies is worth saving, it must reckon with the field’s own sins. One of the most disturbing and delegitimizing trends among security scholars and practitioners of late has been the leap from 20 years of counter-insurgency and terror to “great-power competition.”

The rank failure of the former—practically, intellectually, strategically (!)—should be discrediting. If an entire generation of national security strategists cannot take responsibility for the shortcomings of their past analysis and judgment—especially when it was anchored in little more than a political zeitgeist—why should anyone take seriously their analysis today, which is anchored in a new political zeitgeist?

Strategic studies has an obligation to be more than merely intellectual justifications for the ever-shifting fear and opportunism of the ruling class. Every scholar of strategic theory believes that their project ultimately is about making sure that violence obeys reason; wanton violence is evil, whereas reasoned violence offers salvation. This is a pathologically low bar. Even if it makes sense to believe such a thing in the abstract, we know in practice that even the most obscene, unjustifiable, genocidal uses of violence can drape themselves in the rhetoric of necessity. Your job has to be more than Violence + Reason = Strategic Theory.

An antiwar skeptic might push back and say strategic studies doesn’t need to be saved, it needs to be thrown in the trash heap. I’m sympathetic to this sentiment, but as Bull also remarked, a narrowness of vision:

is the occupational disease of any specialist, and the remedy for it lies in entering into debate with the strategist and correcting his perspective.

Remaining wilfully aloof of strategic theory in the face of a power structure where it still has currency in shaping elite decision-making is to cede space to those whose ideas you find most repugnant. That amounts to abandoning a commitment to least-harm, which is the commitment that justifies being critical of strategic studies in the first place. Most importantly, policy itself is one of the terrains of struggle for a better world, and that means optimal policies need to be fought for even if it’s wonky and esoteric to most people and your political horizons go well beyond it.

Critique and Rescue

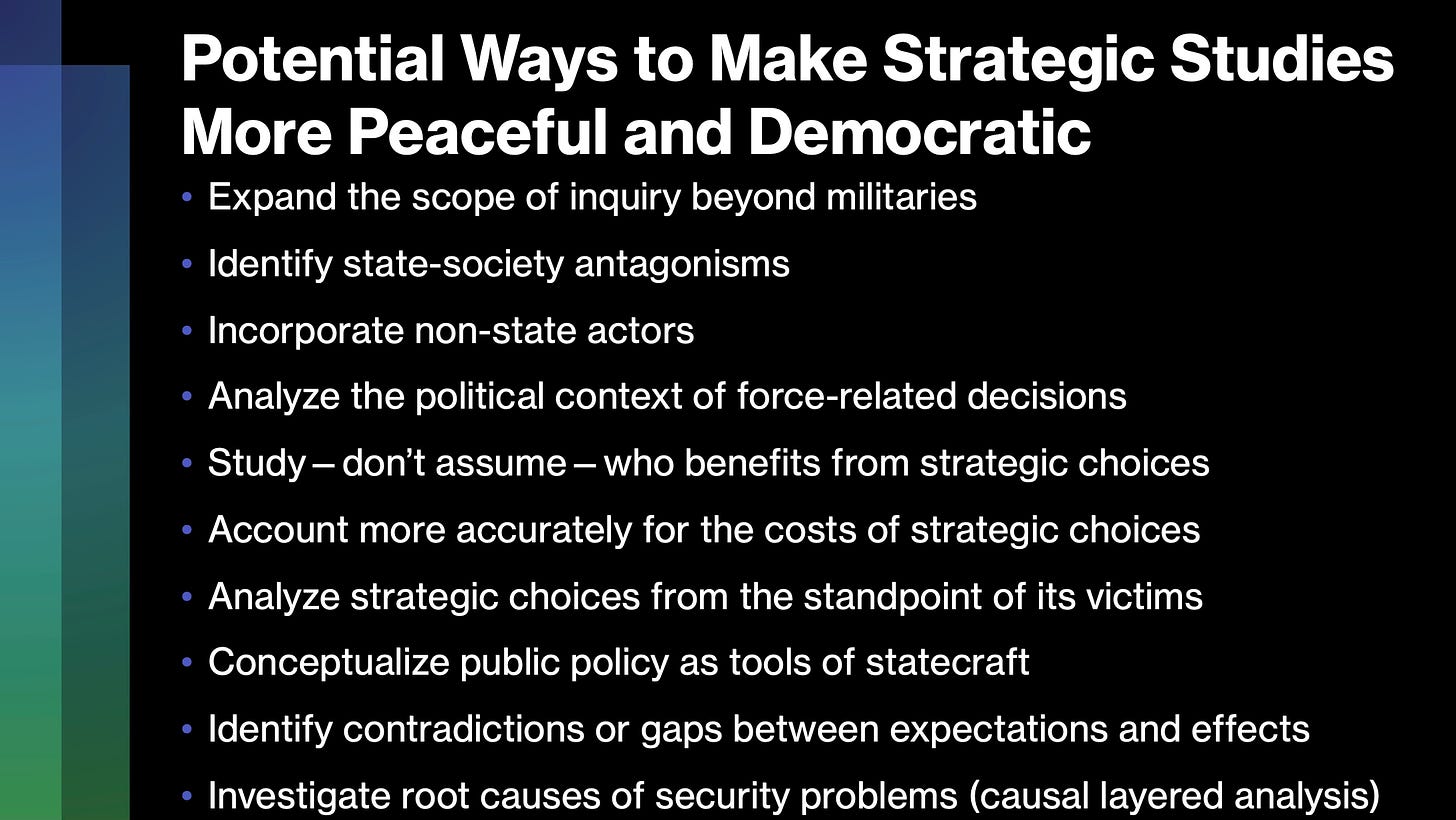

And so, for me at least, the question is not whether to abandon strategic theory to the megalomaniacs of the world who think nuclear wars are winnable, civilian casualties are “negative externalities,” and status-quo hierarchies reflect the best of all possible worlds. Rather, it is to contemplate how strategic studies might better serve the interests of peace, democracy, or equality—aims that are surely in the “national interest.”

So we must ask some new first-order questions.

Who gets to be a strategist? What ought to be their referent objects? How does shifting referent objects shift the insights we glean from history? What means ought to be available to the strategist? How do we account for the full costs of strategic choices? How do we integrate conjunctural and causal analysis? And how does morality affect the field of forces within which strategists fashion solutions to problems?

This is my point of departure for designing a new curriculum in strategic studies. A more critical strategic studies.

While we need some fluency in the grammar of traditional strategic theory and its obsession with militarized violence, we also need a series of concepts that help us account for contradictions, hidden costs, and perverse benefits of violence. We need to stress historical process over historical cherry-picking or abstraction. We need to think about the interplay between root causes and proximate causes. And we need to consider how making peace an object requires configuring the national security state and its choices differently.

On these grounds, I’ve de-emphasized (not erased) Clausewitz and Sun Tzu in favor of Antonio Gramsci and Aimee Cesaire. I’ve revisited the promise of the “non-offensive defense” tradition. And I’ve balanced what strategic theory could look like when practiced by guerrillas, anarchists, and counterinsurgents with what it could like if strategic theory took peace seriously, or if social movements were the strategists. If peace, democracy, or equality were the field’s purpose, strategic studies would not need to be self-abnegating.

So below is my provisional syllabus for saving strategic studies from itself.

Part 1: FOUNDATIONS OF STRATEGIC THEORY

1 What is Strategy?

Key Issues:

- Origins of strategic studies

- Its relation to security studies

- The problems of strategy

- The biases of the field

Readings:

- Van Jackson, “Critical Strategic Studies, or Where Are the Peace Strategists?” Duck of Minerva (December 16, 2022).

- Hew Strachan, “The Lost Meaning of Strategy,” Survival Vol. 47, no. 3 (2005), pp. 33-54.

- Hedley Bull, “Strategic Studies and Its Critics,” World Politics Vol. 20, no. 4, (1968), pp. 593-605.

- Richard Betts, “Is Strategy an Illusion?” International Security Vol. 25, no. 2 (2000), pp. 5-50.

- Richard Betts, “Should Strategic Studies Survive?” World Politics Vol. 50, no. 1 (1997), pp. 7-33.

- [only read pp. 53-65!!!] Michael Handel, “Who is Afraid of Carl Von Clausewitz?” in Strategic Studies: A Reader, 2nd edition, edited by Thomas Mahnken and Joseph Maiolo (New York: Routledge, 2014), pp. 53-75.

2 Grand Strategy and Its Limits

Key Issues:

- The politics of strategy

- Power versus purpose

- Strategy for whom

- The “national interest”

Readings:

- John Lewis Gaddis, “Grammar, Logic, and Grand Strategy,” in The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital Age, edited by Hal Brands (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023), pp. 1119-1140.

- Dan Drezner, Ron Krebs, and Randall Schweller, “The End of Grand Strategy: America Must Think Small,” Foreign Affairs (2020), pp. 1-15.

- Van Jackson, “Grand Strategy is Worldmaking,” Duck of Minerva (October 25, 2022).

- Daniel Nexon, “Strategies of Unusual Size,” Duck of Minerva (May 6, 2022).

- Thomas Meaney and Stephen Wertheim, “Grand Flattery: The Yale Grand Strategy Seminar,” The Nation (2012).

3 From War to Coercion and Back Again

Key Issues:

- The nuclear revolution and its discontents

- Rationality

- Distinguishing force from coercion

- Credibility and commitment problems

- Signaling capabilities v. intentions

- Contradictions of deterrence

Readings:

- [Recommended, not required] Charles Glaser, “Political Consequences of Military Strategy: Expanding and Refining the Spiral and Deterrence Models,” World Politics Vol. 44, no. 4 (1992), pp. 497-538.

- Patrick Bratton, “When is Coercion Successful? And Why Can’t We Agree on It?” Naval War College ReviewVol. 58, no. 3 (2005), pp. 99-120.

- James Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests: Tying Hands Versus Sinking Costs,” Journal of Conflict Resolution Vol. 41, no. 1 (1997), pp. 68-90.

- Scott Sagan, “Nuclear Revelations About the Nuclear Revolution,” Texas National Security Review. Vol. 4, no. 3 (2021), pp. 135-8.

- Bernard Brodie, “The Development of Nuclear Strategy,” International Security Vol. 2, no. 4 (1978), pp. 65-83.

- Carol Cohn, “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals,” Signs Vol. 12, no. 4 (1987), pp. 687-718.

4 Blowback, Boomerangs, and Imbalances

Key Issues:

- Imperial overstretch

- Blowback

- Primacy versus balance of power

- Boomerang effects

- Antagonistic versus collaborative security

- Sacrifice zones and hidden costs

- Cult of the offensive

Readings:

- Christopher Layne, “The Unipolar Illusion Revisited: The Coming End of the United States’ Unipolar Moment,” International Security Vol. 31, no. 2 (2006), pp. 7-41.

- Robert Jervis, “International Primacy: Is the Game Worth the Candle?” International Security Vol. 17, no. 4 (1993), pp. 52-67.

- Stephen Marrin, “The 9/11 Terrorist Attacks: A Failure of Policy Not Strategic Intelligence Analysis,” in Intelligence and National Security Vol. 26, no. 2-3 (2011), pp. 182-202.

- Cynthia Miller-Idriss, “From 9/11 to 1/6, the War on Terror Supercharged the Far Right,” Foreign Affairs (August 24, 2021).

- Ryan Juskus, “Sacrifice Zones: A Genealogy and Analysis of an Environmental Justice Concept,” Environmental Humanities Vol. 15, no. 1 (2023), pp. 3-24.

- Marcus Raskin, “Democracy Versus the National Security States,” Law and Contemporary Problems Vol. 40, no. 3 (1976), pp. 189-220.

- Chalmers Johnson, “American Militarism and Blowback: The Costs of Letting the Pentagon Dominate Foreign Policy,” New Political Science Vol. 24, no. 1 (2002), pp. 21-38.

- Stephen Graham, “Foucault’s Boomerang: The New Military Urbanism,” Open Democracy (February 14, 2013).

- Listen to Big Brain podcast, “Rise of the White Power Movement with Kathleen Belew.”

- Teresia Teaiwa, “Bikinis and Other S/Pacific N/Oceans,” The Contemporary Pacific Vol. 6, no. 1 (1994), pp. 87-109.

5 Guerilla War, Terrorism, and Counter-Insurgency

Key Issues:

- Does COIN work?

- Is terrorism logical?

- When violence against the state works

- Proxy forces

- Propaganda of the deed?

- Foco theory

Readings:

- Jordan Michael Smith, “BIG BOOM: Robert Pape Remakes Terrorism Studies,” World Affairs Vol. 173, no. 5 (2011), pp. 97-100.

- Christian Tripodi, “Hidden Hands: The Failure of Population-Centric Counterinsurgency in Afghanistan 2008-11,” Journal of Strategic Studies (2023).

- Ahmed Hashim, “Strategies of Jihad: From the Prophet Muhammad to Contemporary Times,” in The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital Age, edited by Hal Brands (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023), pp. 946-971.

- S.C.M. Paine, “Mao Zedong and the Strategies of Nested War,” in The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital Age, edited by Hal Brands (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023), pp. 638-662.

- Listen to Un-Diplomatic Podcast episode 172, “The Reactionary Worldmaking of Counter-Insurgency, with Joseph Mackay.”

- Thomas Lim and Eric Ang, “Comparing Grey-Zone Tactics in the Red Sea and the South China Sea,” The Diplomat (April 20, 2024).

- John Haines, “How, Why, and When Russia Will Deploy Little Green Men—and Why the US Cannot,” Foreign Policy Research Institute (March 9, 2016).

PART 2: NEW DIRECTIONS FOR STRATEGIC THEORY

6 Strategic Theory from Below

Key Issues:

- Gramsci’s war of maneuver v. war of position

- Social movements

- Class conflict

- Anti-fascism

- Protest tactics

Readings:

- Priya Satia, “Strategies of Anti-Imperial Resistance: Gandhi, Bagat Singh, and Fanon,” in The New Makers of Modern Strategy: From the Ancient World to the Digital Age, edited by Hal Brands (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2023), pp. 440-467.

- Serena Adlerstein, “The Ten Components of Good Strategy,” Convergence Magazine (November 2, 2023).

- Daniel Egan, “Rethinking War of Maneuver/War of Position: Gramsci and the Military Metaphor,” Critical Sociology Vol. 40, no. 4 (2013), pp. 521-38.

- Elizabeth Frazer, “The Diversity of Tactics: Anarchism and Political Power,” European Journal of Political Theory Vol. 18, no. 4 (2019), pp. 553-64.

- Joshua Wong, “Hong Kong’s International Front Line,” Journal of International Affairs Vol. 73, no. 2 (2020), pp. 261-8.

- Max Elbaum, “Beat MAGA, Shape the Direction of the Country,” Convergence Magazine (March 24, 2023).

- Max Elbaum, “Key to Strategy #3: Assess the Balance of Forces,” Convergence Magazine (February 18, 2022).

- Midwest Academy Strategy Chart (not a reading, just a chart/guide).

7 Non-Offensive Defense Strategy

Key Issues:

- Offense-defense balance

- 3:1 rule

- Confidence building

- Dilemmas of the security dilemma

- Cooperation spirals

- Signaling intentions v. signaling capabilities

Readings:

- [Recommended, Not Required] Sean Lynn-Jones, “Offense-Defense Theory and Its Critics,” Security Studies Vol. 4, no. 2 (1995), pp. 660-91.

- Randall Forsberg, “Confining the Military to Defense as a Route to Disarmament,” World Policy Journal Vol. 1, no. 2 (1984), pp. 285-318.

- Bjorn Moller, “The Post-Cold War (Ir)Relevance of Non-Offensive Defence,” Copenhagen Peace Research Institute Working Paper (1997).

- Carl Conetta, Charles Knight and Lutz Unterseher, “Defensive Military Structures in Action: Historical Examples” (May 1994). Originally published in Confidence-Building Defense: A Comprehensive Approach to Security & Stability in the New Era, Study Group on Alternative Security Policy (Bonn, Germany) and Project on Defense Alternatives (Cambridge, MA, USA).

- Carl Conetta and Lutz Unterseher, Confidence-Building Defense: A Comprehensive Approach to Security and Stability in the New Era, Study Group on Alternative Security Policy and Project for Defense Alternatives (1994), pp. 1-6, 15-25, 55-68.

- Matt Evangelista, “A ‘Nuclear Umbrella’ for Ukraine? Precedents and Possibilities for Postwar European Security,” International Security Vol. 48, no. 3 (2024), pp. 7-50.

- Anders Boserup, “Common Security and the Concept of Non-Offensive Defense,” in A Just Peace Through Transformation: Cultural, Political, and Economic Foundations for Change (New York: Routledge, 1989), pp. 455-69.

- Frank von Hippel, “The Role of Non-Offensive Defense in Ending the Cold War,” Symposium: Toward a Theory of Peace: Randall Forsberg and Her Legacy, Cornell University, 14 Sept. 2018.

8 Strategizing for Peace

Key Issues:

- Peacebuilding v. peacekeeping v. peacemaking

- Unilateral accommodation v. reciprocity

- GRIT

- Rapprochement

- Ripeness

- Peace signaling

- Trust v. credibility

- Security beyond the balance of power

Readings:

- Robert Johansen, “Toward an Alternative Security System: Moving Beyond the Balance of Power in the Search for World Security,” Alternatives Vol. 8, no. 3 (1982), pp. 293-349.

- Richard Jackson, “Bringing Pacifism Back into International Relations,” Social Alternatives Vol. 33, no. 4 (2014), pp. 63-6.

- Sara Hellmuller, “Peacemaking in a Shifting World Order: A Macro-level Analysis of UN Mediation in Syria,” Review of International Studies Vol. 48, no. 3 (2022), pp. 543-59.

- Randall Forsberg, “Creating a Cooperative Security System,” Boston Review Vol. 17, no. 6 (1992), pp. 7-10.

- I. William Zartman, “The Timing of Peace Initiatives: Hurting Stalemates and Ripe Moments,” Global Review of Ethnopolitics Vol. 1, no. 1 (2001), pp. 8-18.

- Charles A. Kupchan, How Enemies Become Friends: The Sources of Stable Peace (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), pp. 1-15.

- Toshio Yamagishi, Satoshi Kanazawa, Rie Mashima, and Shigeru Terai, “Separating Trust from Cooperation in a Dynamic Relationship,” Rationality and Society Vol. 17, no. 3 (2005), pp. 275-308.

- Frank Aum and George Lopez, “A Bold Peace Offensive to Engage North Korea,” War on the Rocks (December 4, 2020).

PART 3: CONTEMPORARY CHALLENGES IN STRATEGIC THEORY

9 Asian and Pacific Geopolitics

Key Issues:

- The meaning of great-power competition

- Spheres of influence

- The balance of power in strategic context

- Encirclement dilemma

- Détente

- Grand bargain logic

Readings:

- Van Jackson, “Relational Peace Versus Pacific Primacy: Configuring US Strategy for Asia’s Regional Order,” Asian Politics & Policy Vol. 15, no. 1 (2023), pp. 141-52.

- Charles Glaser, “A US-China Grand Bargain? The Hard Choice Between Military Competition and Accommodation,” International Security Vol. 39, no. 4 (2015), pp. 49-90.

- Jake Werner, “Why Did the China-US Relationship Collapse, and Can It Be Repaired?” The Nation (November 21, 2022).

- Paul Staniland, “The Myth of the Asian Swing State,” Foreign Affairs (May 2, 2024).

- Meg Taylor, “Pacific-Led Regionalism Undermined,” Asia Society Policy Institute (September 25, 2023).

- Wei Da, “Security Concerns are Reasonable, Spheres of Influence are Not,” The Washington Quarterly Vol. 45, no. 2, (2022), pp. 93-104.

- Lindsey O’Rourke and Joshua Shifrinson, “Squaring the Circle on Spheres of Influence: The Overlooked Benefits,” Washington Quarterly Vol. 45, no. 2 (2022), pp. 105-24.

- Watch Andrea Bartoletti, “Escaping the Deadly Embrace: Encirclement at the Origins of World War I” (May 4, 2021).

- Watch Alastair Iain Johnston, Kippenberger Lecture at VUW, “Identity, Race, and US-China Conflict,” (June 6, 2023).

- Ankit Panda, “New U.S. Missiles in Asia Could Increase the North Korean Nuclear Threat,” Foreign Policy (November 14, 2019).

10 The Emerging Technology Problematique

Key Issues:

- The offense-defense balance

- Entanglement risks

- Outer space

- Drone warfare

- Strategic non-nuclear weapons

- A.I.

Readings:

- Andrew Futter and Benjamin Zala, “Strategic Non-Nuclear Weapons and the Onset of a Third Nuclear Age,” European Journal of International Security Vol. 6, no. 3 (2021), pp. 257-77.

- Antonio Calcara, Andrea Gilli, Mauro Gilli, and Ivan Zaccagnini, “Will the Drone Always Get Through? Offensive Myths and Defensive Realities,” Security Studies Vol. 31, no. 5 (2022), pp. 791-825.

- Sumantra Maitra, “How Drones Are Changing War,” The American Conservative (December 11, 2023).

- Ben Garfinkel and Allan Dafoe, “Artificial Intelligence, Foresight, and the Offense-Defense Balance,” War on the Rocks (December 19, 2019).

- Yuval Abraham, “‘Lavender’: The AI machine directing Israel’s bombing spree in Gaza,” +972 Magazine (April 3, 2024).

- Ankit Panda, “Hypersonic Boost-Glide Weapons and Challenges to International Security,” The Diplomat (November 16, 2018).

11 Environmental Harm and Planetary Concerns

Key Issues:

- Planetarity

- Sacrifice zones

- Resource wars

- Climate colonialism

- Securitization dilemmas

- Radical solutions

Readings:

- Nathan Gardels, “The Third Great Decentering,” Noema Magazine (April 5, 2024).

- Jon Barnett and W. Neil Adger, “Climate Change, Human Security and Violent Conflict,” Political Geography Vol. 26, no. 6, (2007), pp. 639-655.

- Daniel Deudney, “Muddled Thinking,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Vol. 47, no. 3, (1991), pp. 22-28.

- Lorraine Elliott, “Human Security/Environmental Security,” Contemporary Politics Vol. 21, no. 1 (2015), pp. 11-24.

- Watch or read the transcript for “‘Cobalt Red’: Smartphones & Electric Cars Rely on Toxic Mineral Mined in Congo by Children,” Democracy Now (July 13, 2023), https://www.democracynow.org/2023/7/13/cobalt_red_kara.

- Christos Zografos and Paul Robbins, “Green Sacrifice Zones, or Why a Green New Deal Cannot Ignore the Cost Shifts of a Just Transition,” One Earth (November 20, 2020).

- Vincent Emanuele, “Interview: Christian Parenti on Climate Change, Militarism, Neoliberalism, and the State,” Truthout (May 12, 2015).

- Christian Parenti, “A Radical Approach to the Climate Crisis,” Dissent (2013).

- Wen Stephenson, “No Safe Options: A Conversation with Andreas Malm,” LA Review of Books (January 5, 2021).

- Michael Klare, “Will There Be Resource Wars in Our Renewable Energy Future?” Salon (May 31, 2021).

0 Comments