Debate over the proposal has broken down along the usual lines. Unsurprisingly, Marginal Revolution co-blogger Alex Tabarrok offers two cheers in favor of the scheme, dissenting only on the implementation (that instead of targeting STEM in particular the subsidies for selected majors should reflect the externalities of those majors … which, Tabarrok suggests, will mean subsidizing STEM). Meanwhile, displaying the sort of reasoning skills that belie the claims that studying the liberal arts makes you a better rhetorician, one undergrad protests that making her pay more will make her pay more:

Joanna Mandel, a theater student at Florida Atlantic University, said it would straddle students with debt they might not be able to repay. “Theater majors or English majors are not guaranteed to make a lot of money,” said the 22-year-old from Pembroke Pines. “Doctors and scientists, they make a lot of money. If anything, they should be paying more.”

Of course, the entire point is precisely that it’s hard for the state to see a return on those investments. In the Baby Boomers’ youth, when state budgets were less encumbered by pension obligations and other long-term debts, this wasn’t so urgent; moreover, of course, the pay distinction between different majors wasn’t all that great. In those circumstances, the argument that college wasn’t a pecuniary transaction carried more weight. Now that the Baby Boomers have declared generational warfare on my cohort, of course, there’s suddenly no more money to fund higher education and so conservatives and green eyeshades-types have gotten very interested in calculating rates of return on public spending.

Obviously, as political scientists, we all recognize immediately that this program is woefully misguided because it will likely cut the number of political science majors in Florida. Less flippantly, I think we all wonder whether the knock-on effects of this policy will be good for the country (or, at least, Florida). Yet I think that the argument against these measures is less obvious than it appears.

In the first place, it appears to be a simple fact that the American public is not particularly interested in funding the vision of higher education that academics cherish. If we as academics also cherish democratic responsiveness, then we should begin to consider proposals that change the university to fit its changed circumstances. Indeed, this is nothing new. Many of the public universities we rely on were once the products of nineteenth-century public policy designed to teach the sons of the state how to till the soil and build machinery more effectively (and the daughters to better manage the home). That was an innovation as alien to the Oxford and Cambridge model of higher education as the iPod is to the orchestral model of music production.

The standard academic rallying cry is that higher education, as such, has positive externalities to the point that it approximates a public good (that is, that we should tax even those who don’t enroll in college to support university educations). That may be so. This argument, however, is ultimately self-defeating, since it only requires someone like Gov. Scott to ask whether some majors are better for the public than others. And that, too, is almost certain. In that case, to maximize the public welfare, we should be only funding certain majors (recall in this case that we do not value inquiry for its own sake). By granting the premise that the public-goods justification is acceptable, defenders of the university have opened the door to the piecemeal subsidization of various majors. Perhaps it would have been better to stress the value of inquiry and of knowledge for its own sake; but perhaps some private donors or the publics of the European Union, India, or the People’s Republic of China will take up that mantle.

(I should note that the more powerful argument against this sort of arrangement on rightist terms is that for many majors the government is, essentially, the price-setter. How much is a degree in secondary education worth? That question is inseparable from how much the government, writ large, intends to pay for the services that those majors qualify their students for–which, by definition, is only weakly influenced by the market.)

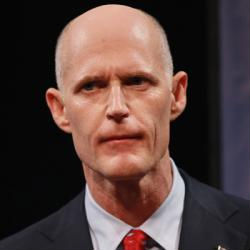

What Tabarrok, Scott’s task force, and Joanna Mendel all miss, however, is how such a funding mechanism would transform disciplinary content and practice. It would, to a first approximation, likely kill off traditional humanities. Yet it would also incredibly privilege variants of economics, political science, and sociology that have high statistical or other quantitative content. I would also hope, quixotically, that we would quickly learn that majors offered by many business schools are hardly worth the time. But somehow I doubt that any social-scientific data offered along those lines would impress successful businessmen like Rick Scott.

While perhaps interesting on its own terms, I wonder if this is missing an even more important dynamic. Public universities are less reliant on state funding than ever before. At UMichigan roughly 17% of the university budget comes from the state. At IndianaU it’s 16%. UTexas is 13%. The UC system is around 15%. At UNC it’s around 20%.

What does that mean? Increasingly, state legislatures have little leverage over universities. And because universities are getting revenue from other sources (endowments, sponsorships, tuition) they will naturally tend to cater to the places that can generate that funding. Increasingly, this is STEM and the quantitative social sciences.

This might not immediately appear as subsidized tuition for preferred majors, but it will function as such. How? Scholarships will be increasingly given to students who demonstrate the sort of aptitude that would make them more likely to succeed in STEM programs, and/or those that actually express an interest in STEM programs. This is a literal discount for STEM majors. New investments in the university will go to STEM — new buildings, new labs, new computers, more research funds — while the humanities get the run-down facilities, fewer course offerings with more students per instructor, etc. This is a backdoor tuition subsidy for STEM, since getting access to greater resources for the same tuition is a net benefit for STEM majors. Moreover, investments in STEM that allow the university to move up in the rankings will lead to greater earnings potential for STEM graduates, thus implying a further subsidy for STEM. The rising burden of debt makes this even more important.

All of these things and more are already happening. Is it a bad thing? It depends. More Americans are enrolling in college now than ever before. Only 16% of them complete STEM majors. Another 16% complete social sciences. 12% complete humanities and 23% complete business (https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2011/2011236.pdf). That doesn’t strike me as being disproportionately skewed towards STEM, particularly given the relative unemployment rates in varying sectors (i.e., it’s not good to graduate students into job markets where they are unemployable) and the fact that STEM covers a very large bundle of majors.

Moreover, students in STEM majors generally are required to take a number of core classes in the social sciences and humanities anyway; just because they aren’t *majoring* in German lit doesn’t mean that they’ve avoided classes which emphasize “inquiry for its own sake” altogether. In any case, that phrase applies just as well to many STEM programs as it does to many humanities and social science programs.

I’m not sure that states can or should put their thumb on the scales to further this trend, but they don’t need to. So long as college is treated as an accreditation service for labor markets — by everyone, especially students and their parents — the fields with the greatest employment potential will attract the most resources.

By your logic, then, universities will try even harder to squeeze out non-STEM/non-vocational students. But they’ll either have to do this via tricky manipulation of student aid or by strict rationing of departments. My impression is that either of these has been very difficult to get by faculty senates. I instead simply presume that public universities will stagnate and be vulnerable to disruptive innovations.

My impression is that there’s actually comparatively few students who are STEM majors who actually take higher-level courses in non-STEM fields; thus, you could get away by completely adjunctifying the English faculty as tenured profs die off, cut out classes above the 200-level, and realize even greater cost savings there.

Neither of these futures bodes well for the 100-level intro to US Politics course as it’s currently taught.

(And they especially bode poorly for political theory.)

Maybe. There are other possible dynamics which are less worrying. Perhaps an increased focus on STEM raises money from other sources, which allows universities to divert money they’d ordinarily be spending on STEM to other fields. (This is why I am more sanguine about corporate sponsorships than others… that just frees up money for universities to divert to other departments.) Perhaps streamlining departments encourages the development of economies of scale, as many universities are trying to do by merging languages, area studies, and other departments into “Global Studies” centers. This isn’t always accommodated by cuts to classes or faculty, but it does reduce redundancy in course offerings, administration, and facilities. And keep in mind that student demand is still the biggest factor. If students want humanities classes they’ll get them. What they actually get out of them is another matter.

A final point to make is that the liberal arts education is pretty unique to America. In many other types of university systems, students focus on their “major” more or less from the moment they matriculate until the moment they graduate. This doesn’t strike me as an implicitly *worse* model… just a different one. And the humanities survive in those systems. If the US higher education moves a bit towards other models that might be okay, although it will obviously require some adjustment. But these things tend to happen gradually.

I remember in the 80’s hearing my parents say that in communist countries the government chose your career for you and horrible that was. Oh, the irony!

Perhaps publicly funded schools should just not offer majors that are not deemed to be of a lot of benefit to society. Private schools do an excellent job of teaching the “artsy” majors that rarely lead to employment. And if a lot fewer people take a degree in those majors, supply will more closely match demant and maybe an art history degree will become worth something again.

No attempt should be made to regulate what majors private schools teach.