Thanks to the patience of the former EJIR editorial team, PTJ and I will have an article in the forthcoming special issue on the “End of IR Theory?” Only the first 35-40% resembles the working paper (PDF) we posted at the Duck. Even the name has changed.

We still argue in favor of thinking about international-relations theory as dealing with “scientific ontologies”: “catalog[s]–or map[s]–of the basic substances and processes that constitute world politics.” As we note in both the final version and the working paper, this includes:

- The actors that populate world politics, such as states, international organizations, individuals, and multinational corporations;

- The contexts and environments within which those actors find themselves;

- Their relative significance to understanding and explaining international outcomes;

- How they fit together, such as parts of systems, autonomous entities, occupying locations in one or more social fields, nodes in a network, and so forth;

- What processes constitute the primary locus of scholarly analysis, e.g., decisions, actions, behaviors, relations, and practices; and

- The inter-relationship among elements of those processes, such as preferences, interests, identities, social ties, and so on.

Contributors are prohibited from posting further revisions online. But I thought I would share what we think the current landscape of international-relations theory looks like. Or, to clarify, what kind of a topography of implicit debates satisfies the following criteria:

- Reconstruct already existing terms of debate;

- Deal with more fundamental—and therefore much broader—concerns of scientific ontology than did the ‘isms’; and

- Involve gradations of disagreement rather that purport to describe self-contained theoretical aggregates.

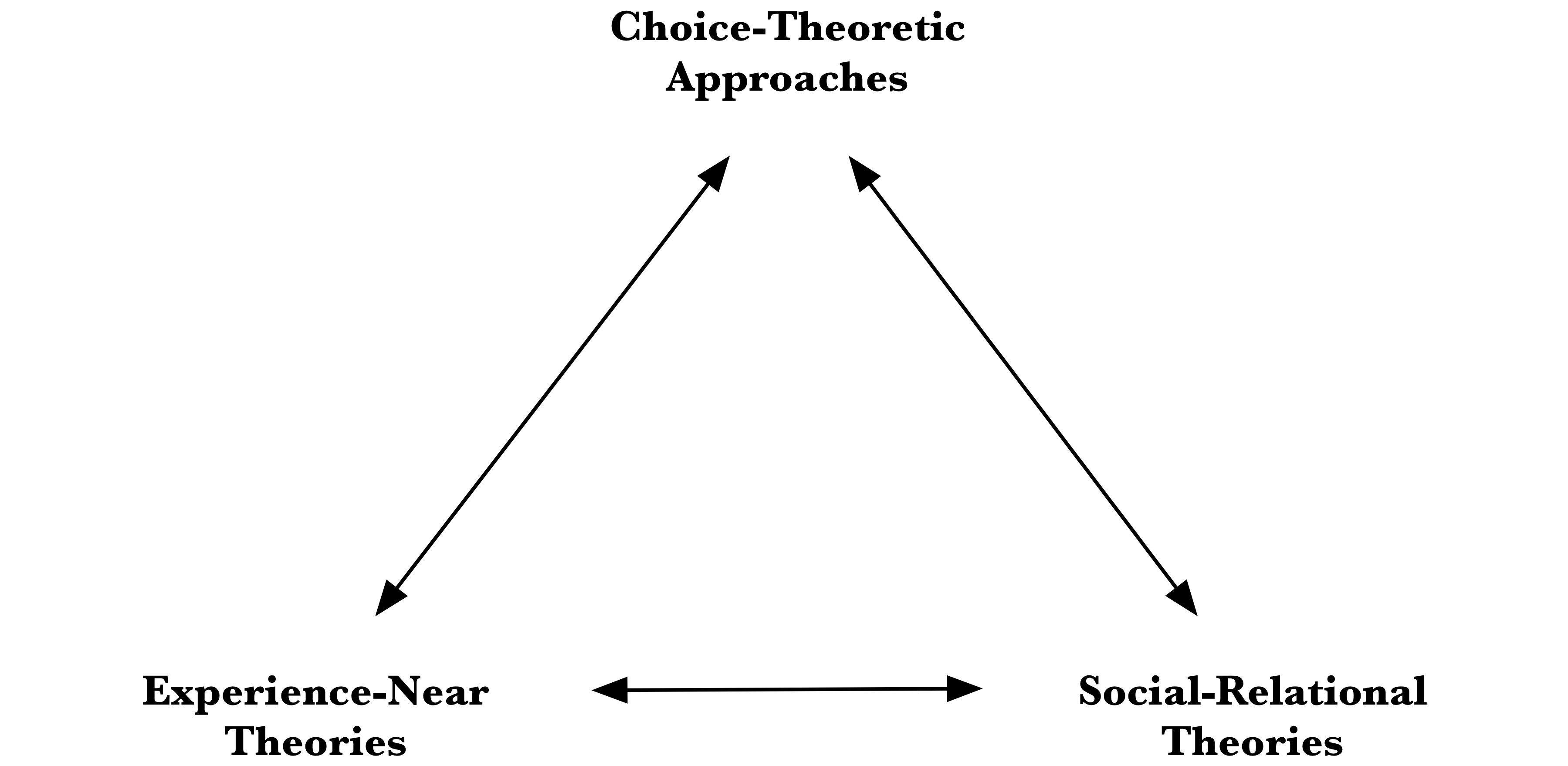

The three clusters of basic scientific ontologies we flag are choice-theoretic, experience-near, and social-relational. The terms of contestation involve two questions.

First, “the degree that actors may be treated as autonomous from their social, cultural, and material environments—that actors are analytically distinguishable from the practices and relations that constitute them.” Choice-theoretic approaches tend to treat actors as autonomous from their environments at the moment of interaction, not so experience-near and social-relational alternatives.

Second, “the degree of thick contextualism—the commitment to theories that give analytic and explanatory primacy to specific features of the immediate spatial-temporal environment in which actors operate, with concomitant skepticism about generalizing or abstracting from particular contexts.” Experience-near approaches embrace thicker contextualism than either social-relational or choice-theoretic.

I am sure that, in the absence of the paper, this all seems pretty abstract.

In general, we see choice-theoretic approaches as including expected-utility theory, some psychological approaches to decision-making, and much of what passes for “logics of appropriateness” work in the field. Experience-near approaches include aspects of the practice turn and what might be called the “new anthropology” in the field. Social-relational approaches include social-network analysis, some aspects of the practice turn — most notably those that focus on the positional and relational implications of social fields — and some forms of post-structural analysis.

As I’ve already suggested, these clusters of theories bleed into one another. Disagreements often involve matters of degree. Regardless, I offer this preview for readers’ consideration.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Looks interesting. Just one quick thought: I know the typology you propose is just that – a useful method for making sense of scientific ontologies in IR – but in the penultimate paragraph it seems to perhaps not include the range of IR approaches out there (*some* psychological theories, *some* forms of post-structuralist analysis). What about the rest? Would they be venn-diagrammed into some sort of cross-over position, or just have idiosyncratic scientific ontologies that cannot be encapsulated by the limitations of the typology?

Yes, venn-diagramming might be better. in the paper, we talk about “modal” theories of each type — and provide more info-rich graphics than this one I mocked up this morning — and try to make clear that many theories operating among and between these positions. The key point is that we think these are/should be/might be the questions at the heart of developing theoretical debates.

It’s very interesting, D. What I like is the split in practice turn b/t experience near and social relational. It captures those who want to use Bourdieu’s work as method, and those who want to use it as critique… and by extension the broader question of how critical sensibilities do or do not get folded into practical reason and what practical reason is put toward…the field as an object of discussion or ‘the world’…

Less clear to me is the actual status of these categories. are they analytical or ontological? How much control over our ‘stances’ do we have? Is a theorist ‘cut’ from a certain kind of intellectual ‘cloth’ or is she ‘made’ by training… of course the answer is particular to each person… but I wonder how much we choose our scholarly sensibilities and how much they choose us, as it were. If the latter — if the theorist is not master of her own house — what does that mean? Are we back to a kind of ancient-greek/polis notion of the field as a ‘microcosm that must contain all kinds?’ Perhaps ethics and reflexive sensibilities come to matter less, because they are ‘given’ to scholars a priori… BDM (say) can only be who he is, and DHN can only be who he is…

I am not persuaded by the attempt to separate all theories that are attentive to actors’ choices from others that appear bring in social relations “really” meaningfully. I realize there may be extremes on the choice-theoretic end (most or all rationalisms,) but to presume that only social network folks and the other two you mention (poststructuralists and practice theorists) take social relations seriously seems to me really begging of a clear justification. I hope that in your article you provide a standard or a way to assess theories’ varying degrees of social relationality.

The list here is not intended to be exhaustive, nor are the more numerous examples in the article. That being said:

1. “attentive to choices” and what we call “choice-theoretic” are different things; the latter describes a specific range of scientific ontologies associated with theoretical explanation, the former an object of analysis, complement of explanation, etc. We have a table in the article that should also help clarify what we mean.

2. As you suggest, These aren’t ideal-typical positions but they are clusters of theories. A lot of theories operate away from the extremes.

3. Because we are attempting to draw out (often implicit) terms of theoretical debate, we’d be pretty happy if we drew a reaction that inspired argument about what it means, for example, to “take relations seriously”! :-)

That triangle looks quite familiar!

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1528-3585.2010.00413.x/full

From a pedagogical perspective, I have certainly found this approach extremely useful for introducing students to the relationship between theory, method, and conduct of research.

This raises two questions for me.

First, why do you consider actors autonomous from their environment a the moment of decision in choice-theoretic approaches? One popular interpretation presently pursued is that the individual is ‘partly’ free from environmental influences, only in the sense that some part of the explanation for an action needs to refer to the individual and that individuals’ decision. Lars Udehn made this distinction in 2002 in Ann Rev Soc. The latter sense of explanation is quite weak, and does not posit individualism in the sense you propose. After all, the individual is not free to choose their (a) interests, (b) available strategies, (c) who they are interacting with, and in fact do not ‘choose’ their decision because that is provided by the structure of the interaction in combination with the psychological factors, etc. that are relevant to the decision. The interpretation you appear to favor, I suspect, may not be the ‘modal’ interpretation in political science or economic theory more generally.

Second, if you take a richer view of choice-theoretic approaches–say call them methodological individualisms that range from weak (the above interpretation) to strong (the one you propose)–then can we easily imagine combining some elements of the choice-theoretic framework with at least some versions of social network analysis? For example, one can easily combine discussions of how strategies, ideas, resources, etc. diffuse or become powerful using social relational analysis, and analyzing how that translates into decisions agents make in light of the network (or other) structures they find themselves, as elements of an explanation of social action.

If this is right, then in what sense are we really talking about clashing ontologies, and not clashing views of the aims of explanation in IR? (note: the difference with experience-near approaches makes a ton of sense to me).

I’m sure the paper answers all of these questions of course.