Editor’s Note: This is a post (mostly) by Patrick Thaddeus Jackson. It is the 14th installment in our “End of IR Theory” companion symposium for the special issue of the European Journal of International Relations. SAGE has temporarily ungated all of the articles in that issue. This post refers to PTJ’s and Daniel Nexon‘s article (PDF). A response, authored by Janice Bially Mattern, will appear at 10am Eastern.

Editor’s Note: This is a post (mostly) by Patrick Thaddeus Jackson. It is the 14th installment in our “End of IR Theory” companion symposium for the special issue of the European Journal of International Relations. SAGE has temporarily ungated all of the articles in that issue. This post refers to PTJ’s and Daniel Nexon‘s article (PDF). A response, authored by Janice Bially Mattern, will appear at 10am Eastern.

Other entries in the symposium–when available–may be reached via the “EJIR Special Issue Symposium” tag.

To begin with the punchline: we feel that the state of international theory globally is considerably more robust than laments about “the end of International Relations theory” would have it. The problem, we argue, is that the mental maps of the field with which so many of us operate do not give pride of place to the theoretical points of contention that actually do unite the field by giving IR scholars a set of debates within and against which to locate their own scholarly work. The perception of excessive theoretical fragmentation is thus an artifact of the way we conventionally map the field, and accordingly, what has to change are our maps — not IR theory.

There are three conventional ways of mapping the universe of IR theory, all of which have relatively serious limitations. The “isms” mapping pits the supposed “paradigms” of realism, liberalism, and constructivism (once upon a time that third was Marxism) against one another; besides unhelpfully turning straightforward empirical disagreements into presumptively “incommensurable” assumptions that function as shibboleths in academic tribal warfare, the “isms” mapping also only permits broad generalizations about the causes of state behavior to qualify as “theory.”

The “great debates” mapping suggests that field-wide contentious conversations spur scholarly innovation, but this mapping suffers from empirical and historical weaknesses (it is unclear, for example, that the “second debate” actually consumed the attention of more than a handful of IR scholars), and also — especially with the “second” and “third” great debates — conflates theoretical and methodological issues in ways that lead us to confuse discussions about international affairs with discussions of the status of our claims about international affairs.

Finally, the recent vogue for “middle-range theory” pushes scholars to focus on more limited generalizations, often involving one or more “standard stories” selected from a basket of conventional propositions about common social mechanisms, such as “incomplete information” or “shaming.” As a map of the field, these middle-range theories don’t offer us much to go on, since different researchers use similar social mechanisms in different ways…and the overall approach valorizes cross-case generalization to the exclusion of the other approaches to the production of knowledge that are in fact alive and well in the field.

As an alternative, we offer a map of the field that is designed around two basic principles: the separation of theory and methodology, and the idea that a good map points to ongoing disagreements rather than to overly solid theoretical camps. In line with the former principle, we argue that international theory consists not of research design principles and philosophies of knowledge, but is instead scientific ontology: a catalog of the “stuff” of interest to the researcher and how it is interconnected. This catalog is relatively independent of methodology, in that different researchers may choose to cash out the same set of substantive concerns in divergent ways: some may conduct large-n hypothesis-tests, some may engage in analytical modeling, etc. While methodological diversity is certainly important, we suggest that mapping the field in terms of methodology obscures the ways that researchers using different techniques and approaches might nonetheless engage in productive conversations underpinned by their similar substantive concerns.

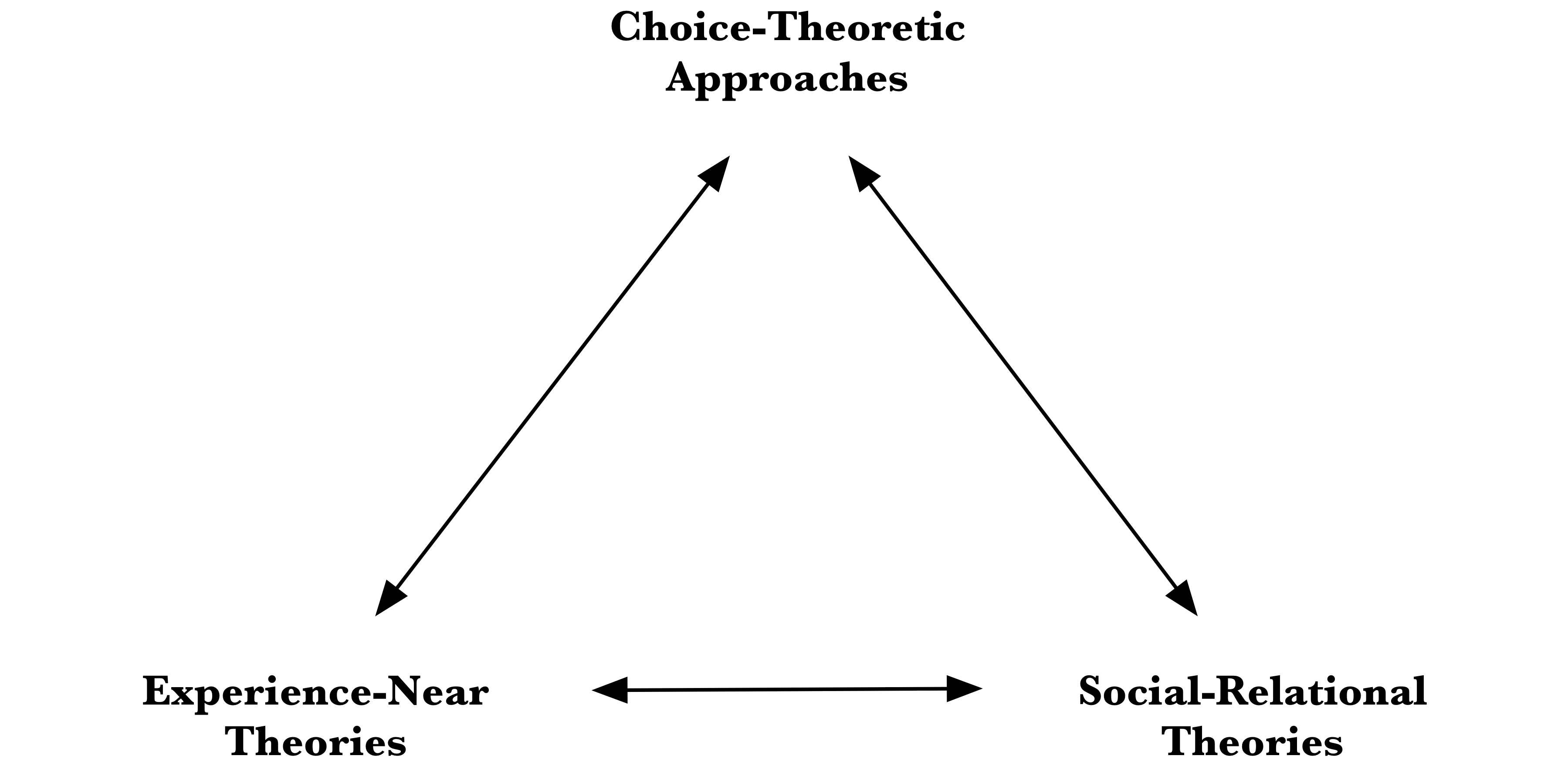

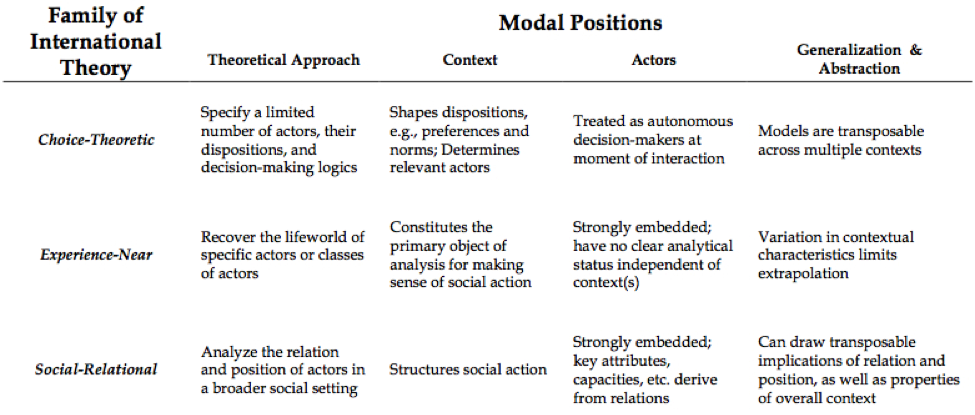

In line with the second principle, we argue that the kinds of wagers that we see IR scholars making in their current lines of research fall along two axes: one axis involving the degree to which actors are thought to be relatively autonomous from or densely connected with their social environments, and another axis involving the degree to which theories and theorists have to be grounded in the thick contextual experiences of actors as opposed to relatively abstracted from those experiences. Combining these axes and labeling the three combinations we see in evidence in current IR scholarship gives us a convenient map:

This map serves the basic function of giving IR scholars things in common to disagree about, and does so by concentrating on substantive wagers about international affairs rather than on the methodological issues better tackled by the philosophy of science. The three theoretical families we identify — choice-theoretic, experience-near, and social-relational — are emphatically neither “paradigms” nor hermetically sealed intellectual camps. But we feel that they identify some emerging theoretical pivots, best glimpsed by examining the (ideal-typcial) modal position upheld by each family:

The aim of this exercise is to illustrate the extent to which IR theory is in fact developing and diversifying, and to identify the lines of contentious conversation along which it might develop in the future. Choice-theoretic approaches tend to differ from the other two families on the question of actor embeddedness, but choice-theoretic and social-relational approaches share a commitment to transposable models and abstract causal claims that sometimes puts them at odds with experience-near theory. These are not insurmountable barriers as much as they are a limited vocabulary of things to argue about; particular researchers might find themselves and their work located someplace between these ideal-typical modal positions, and it is our hope that this map provides some insight into how such work is received by scholars whose sensibilities are located more towards the extremes.

So: IR theory isn’t ending; it’s actually alive and well, but that fact is obscured by a focus on older maps of the field which look for theoretical innovation in all the wrong places. We should not expect new “great debates” or “isms,” and we should not unnecessarily limit ourselves to cross-case generalizations using a grab-bag of social mechanisms. We should instead focus on what we actually have, which is a set of contentious conversations about important substantive matters.

Daniel H. Nexon is a Professor at Georgetown University, with a joint appointment in the Department of Government and the School of Foreign Service. His academic work focuses on international-relations theory, power politics, empires and hegemony, and international order. He has also written on the relationship between popular culture and world politics.

He has held fellowships at Stanford University's Center for International Security and Cooperation and at the Ohio State University's Mershon Center for International Studies. During 2009-2010 he worked in the U.S. Department of Defense as a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow. He was the lead editor of International Studies Quarterly from 2014-2018.

He is the author of The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change (Princeton University Press, 2009), which won the International Security Studies Section (ISSS) Best Book Award for 2010, and co-author of Exit from Hegemony: The Unraveling of the American Global Order (Oxford University Press, 2020). His articles have appeared in a lot of places. He is the founder of the The Duck of Minerva, and also blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

Mmhhh, I hate to say it (well that’s a lie I’m loving being able to say it) but doesn’t the idea that the current maps don’t get it right, and that we need to change the maps, not the theory, imply a dualism (I’d say realism, but dualism will do)? After all, on a monist metaphysics if the maps change so would the theory, but you’re (whoever you are; Dan, or Patrick; or maybe Danrick? :)) are suggesting that what we need to change is the maps and the theory is doing just fine. Curious eh? And even if you want to change the maps just on the grounds that the current ones are no longer ‘useful’ , you’re still left with the difficult issue of the dualism AND the problem of telling us ‘useful’ for who; me, you, all of us, nobody? :) On a more serious point; aren’t these categories just different semantics to describe the same thing? I call it a tomato, you call it a tomato (I know it doesn’t work when written, that’s the point).

Colin: to be honest, I’m not entirely sure what you’re trying to get at. Is this a claim that the arguments laid out here contradict PTJ’s personal philosophy-of-science commitments?

Dan, yes, that was the flippant point. But the serious one is clear I think.

To be honest, it may be clear to you and other readers. It isn’t to me.

Really? : ‘On a more serious point; aren’t these categories just different semantics to describe the same thing? I call it a tomato, you call it a tomato (I know it doesn’t work when written, that’s the point).’

I would have thought the use of the phrase, ‘on a more SERIOUS point’ highlights it. Maybe I should shout more in comments. :)

What is the “same thing” that they’re describing? Absence further specification, I can’t even begin to answer your question.

Ok, but now you are understanding the question and basically saying that you want me to specify in more detail what the same thing is. Fine, you’ve asked me to be specific ontology; I obviously like that. You have answered it in another reply. You’re trying to develop a typography of major positions in the field. And isn’t the isms approach also a typography of major positions in the field? So two different ways of describing the ‘same thing’ (major positions in the field). Now, as to any assessment of which is a better, more useful, more aesthetically pleasing (add as desired) way of mapping the field then we’d have to have some idea of why we need this new typology. I actually agree with you and PTJ on many points, but I’m not sure if you’ll be able to control how its used (if it is), and I’d happily take a real wager (not a philosophical one) that your categories will eventually function as ‘isms’, even though you say they shouldn’t. Hope that helps, we can discuss more in Warsaw.

I always looking forward to hanging out.

I’m being sincere. You said that the typology describes the “same thing.” What is that “thing?” Is it the isms? Is it PTJ’s 2×2 from his book? Is it that some of the categories are the same?

Because there’s no referent, my initial read was that this had something to do with what I thought might be a claim that PTJ was contradicting himself. You said it was something different. I believe you. But that just leads to the next question: if this isn’t about PTJ’s putative contradiction, then what is the tomato/tomato?

I believe Colin is saying (correct me if I am wrong) that your typology is in danger of function as an -isms debate as well.

That said, I think all knowledge, all concepts are in danger of being reified if they become popular. I know I find myself doing it with PTJs typology from Conduct of Inquiry, for instance. But how responsible is a researcher for the reification that follows, especially when they themselves are not looking to reify anything? Should we just no longer create typologies? In other words, if I am understanding him right I am not convinced by his critique…

Hi MAS, I’m not suggesting that we can do without typologies, or mappings of the field. How could we? As I said in another response to Dan, they can’t control how (if at all) the typology is used, my point about it might get ‘ismified’ (yuk!) is that this process is related to the disciplinary dynamics of the field and goes to a broader issue of how ‘isms’ aren’t just theoretical takes (maps) on the field, but all also identities, or identity constructors.

Ok. That makes sense.

These obviously aren’t “the” isms but, I suppose, they could be made into something similar. But to do that you would have to kick out of most of our arguments, and then you wouldn’t be able to sustain their “paradigm” character very easily in light of their porous boundaries.

Yes I agree with that, but independent of their content, they may well function in particular ways, and in the process get changed. All positions mark sites of exclusion and inclusion (it’s unavoidable, although the poststructuralists have made a valiant attempt to avoid it). And I suppose the next discussion is what those exclusions/inclusions are and just how porous the boundaries are. Remember, I’ve always maintained that SR is very porous as well, but it hasn’t stopped people disagreeing with me, and Wendt’s ‘via media’ came in for severe critique for being too porous (too open to movement across boundaries). Problem is, as I’ve found, you might end up defending the porosity (is it right to drop the ‘u? Spell check says so) more than you push the typology. But genuinely best of luck I’m always open to new ways of looking at these things. And of course, I already agree about the scientific ontology bit, and the open attitude to methods (although I’d also add epistemology to that).

As MAS puts it that’s exactly what I’m suggesting re the isms. But just to be clear, the ‘same thing’ = ‘major positions in the field’. Currently these positions are understood through a typology of isms (although I disagree with your framing of it in terms of realism, liberalism and constructivism) and you are suggesting a different typology. Sorry, to me it seems clear, the ‘thing’ that is referred to in the ‘same thing’ is the ‘major positions’ in the field. Also, you are assuming some link between my (admittedly flippant, although there’s always a sting in that tail for me) point about an implied dualism, and the more serious point. I didn’t intend one. But to dismiss the tomato/tomato issue you’d need some sense of why one way of talking about those ‘major positions’ is better than another, or else you are just left with a tomato/tomato problem. I’m sure you have that set of criteria, but that’s what I was asking for. And if you want to draw a link between this issue and my flippant point, as soon as we start that discussion about why your ‘tomato’ is better than my ‘tomato’ we’ll be back in the terrain of dualism/monism and all sorts of other things. So whilst I agree absolutely with your final claim, ‘ what we actually have… is a set of contentious conversations about important substantive matters.’ It’s how we navigate through those conversations, to what end, and so on that matter.

You are completely right- if you assume that ‘getting it right’ means correspondence with a real world out there. But that is just your interpretation. Getting it right can just as well mean ‘be more clear’, ‘more useful’, or ‘yield more insights’. None of these necessarily imply dualism

No that doesn’t work. I don’t say anything about ‘getting it right’. The dualism is in the distinction drawn between the object of inquiry (in this case theory) and the tools we use to describe that object (the maps). I explicitly raise the issue of utility. So I think that’s addressed. And I’d simply say ask, what would ‘be more clear’ mean; ‘clear about what’ if its not about something? How could we make a determination of clear. Likewise provides more insights? Why would we need more insights if the current maps aren’t getting something wrong? And if so what is that some ‘thing’. Mind you I should say I absolutely agree with their substantive points about scientific ontology (I could hardly do otherwise) and methodology, I’d just extend that latter point to include epistemology as well.

I think this is a larger debate about philosophy (especially, the anti-dualism inherent in Jackson’s Analyticism) and is fairly tangential to the substance of the article.

I think Kant would have an answer to this (put colloquially): the cake is the cake, and stays the way it is, but if the old way of cutting it up won’t do, we gotta start over and cut the cake in a new and more useful way.

The cake is the thing-in-itself (or what you refer to as “IR theory”) and the ‘cutting it up’ is our use of concepts/ideal-types.

This alludes to how Kant thought that the world in-itself doesn’t come pre-packaged with discrete objects (like how a “table” is seen as separate thing from the “floor” it is resting on). Human beings cut up the world by our mental activity/concepts. Nexon and Jackson’s pragmatic use of ideal types is simply saying: IR theory can keep doing what it is doing, but the way we cut it up and think about it (at a ‘meta-theoretical’ level) is previously un-useful and have to change.

Meta-theory simply means here: an examination of current (IR) theory.

Yes, agree, but it’s part of a larger, and longer, debate that I wouldn’t say is tangential to the piece, since the kind of issues you raise are integral to how we think about these issues and may impact (I would say will) on our judgements concerning research practice. V. Happy with the cake and cutting metaphor. Still leaves the question hanging as to why one way of cutting the cake might be preferred to another. Fully accept that utility might be the driving factor, but that still leaves open the question of ‘useful for who and why’.

To continue this philosophical tangent:

I know one person who wouldn’t be happy with the cake metaphor – Socrates. Why? Well, cakes don’t have joints!

The cake metaphor suggests that things-in-themselves are homogeneous and consistent, without properties that would punish, reward or in any way perturb our concepts as they interact with them – our ‘carving up’ is essentially arbitrary; one cutting pattern is as good as any other.

It also suggests that all causation is on the side of the concept and the conceptualiser – the carver’s ideas determine the form of the cake without the cake resisting or guiding its own dissection in any way. The cake is a mute, pliable receptacle that is prostrate before the active, conceptualising agent. A merely passive projection screen.

Socrates’ ‘carving nature at its joints’ is a better realist metaphor (what follows doesn’t really reflect Socrates/Plato’s iteration of this idea but takes it in another direction).

First of all, it’s not naively or chauvinistically realist. After all, the butcher *could* carve up the carcass at any point if he were to saw through the bone – and different, equally competent butchers will carve it up differently. Any dissection pattern is possible and there is no one ‘correct’ pattern. Thus there is still room for epistemological plurality, sensitivity to the particularity of local discourses, recognition of the essentially social nature of knowledge, etc.

However, an expert butcher does not just wildly hack at the carcass or chop away blindly and mindlessly. He is sensitive both to the properties of the carcass as a kind or species *and* the particularities of the carcass as a unique, singular entity. Thanks to his past experience of such animals he knows roughly where the good joints are to be found. He has practical rules of thumb that apply to all forms of butchery. He’s sensitive to the requirements of his customers and so on.

However, he also lets the unique dimensions and contours of this exact specimen influence his motions – this one’s smaller than usual, this one is very sinewy, this bone is unusually curved, etc.

The carcass itself guides his hand as he strips the flesh from the bone. It does not and cannot *determine* his motions but it *perturbs* them. It reacts and interacts. It is perhaps not fully ‘active’ but nor is it passive. It rewards certain motions and penalises others. Its dissection is a practical process, full of situated knowledge but also realism.

The cake is an idealist thing-in-itself. It is passive with respect to its own idealisation. A realist thing-in-itself must interact with its own idealisation in some way. It must have immutable properties that cannot ever be specified in a singular, unquestionable, perfectly corresponding 1-to-1 relationship but which affect, perturb, *co-respond* to epistemic interaction.

p.s. Apologies if there are any vegetarians in the house! Not the most pleasant of allegories but I think it is effective.

It would be pithier and more memorable if you just called it “the inter-ontology debate.”

Putting aside the philosophy-of-science question Colin raises, I’m curious how well readers think this works. We posted a very short version a while back and had significant pushback against our description of “choice-theoretic” work — indeed, it led to long guest blog posts…..

There’s 2 aspects: (a) the focus on ontologies is (I think) a good one but (b) the actual taxonomy looks to me a bit like an update of agent-vs-structure since your taxonomic criteria are to do with (i) nature of actor and (ii) nature of context. It may well be an improved update, but it still looks like agent-structure 2.0.

You may say there’s nothing wrong with that, but maybe it is time to think about ontology in terms other than these. For instance, I think innate or natural desires exist. Darwin said there a natural moral sense in humans. If so, its an important bit of ontology. Where does it fit here? Is heritability part of the actor or the context or something else? Are genes context or actor?

Presumably various forms of genetic or biological determinism could be incorporated into the property space in any number of ways–although those arguments tend, with a few exceptions, to lie outside of some of the “modal” descriptions we provide.

FWIW, what we’re trying to capture is a topography of major positions in the current field. If those positions change, the topography would as well.

Better put a “cave hic dragones!” warning where those nasty “genetic or biological determinists” live :)

A map can be a spur to discovery if it includes not just the outlines of the known continents but also the general location of terra incognito.

[Two latinisms: beat that! :)]

I’m sure I’m starting to come over as awfully pedantic (I can live with that, it’s part of what doing this stuff involves). But I’d insist on a small, but significant amendment to your last sentence. ‘If those positions change, then the typology would also ‘need’ to be changed’. The field could change, but the typology could stay the same; it shouldn’t as it would have become redundant, but there’s no necessary relationship from positions changing to the typology of those things changing.

Hi Dan, well since I agree with much of the substantive points about SO and methodology I’d ask you what you ‘mean’ by ‘how well readers think it works’ (which is why I don’t think the philosophy of science issues can be put aside)? If you mean, is it more useful, then probably only time will tell, since the utility of something in this context will depend on people picking it up and running with it. On the other hand, you mean is it a better way to map the field, that there’s some way to try and test how well our maps are doing so.

I’m not terribly picky about how anyone who bothers to answer chooses to interpret “work.”

Sure, but every answer will (possibly) imply a different set of standards and commitments about what it means for them. In asking the question, you must have some sense of what ‘you’ mean. And that’s why I asked ‘you’ what ‘you’ meant; I wasn’t asking everybody else. . Anyway, I’m not sure you’d be happy if it ‘works’ to maintain the status quo, or ‘works’ to entrench exclusions, or ‘works’ to enforce a consensus that it ‘works’. So whilst you might not be ‘picky’, you do ‘care’; if you didn’t why are you setting it out?

One thing I wonder is how much to differentiate between choice-theoretic and social-relational? Both imply transposability, to some extent, and both may be parsed in the language of causal mechanisms (albeit from presumably different foundations cf. Elster vs MTT for example). It may be that most choice-theoretic approaches pay little attention to ’embeddedness’, but there is at least some pushback by analytical sociologists to be both ‘methodological individualists’ and explain things in terms of relations and processes. Is it merely a question of microfoundations? I mean, they constitute discrete bodies of scholarship, but I see them as being potentially far closer to one-another than they both are to the ‘experience-near’ approach.

In some ways yes, but in other ways not.

1. A number of theorists serve as touchstones for experience-near *and* social-relational work. This is particularly true for variants that are often lumped together under the umbrella of “constructivism.”

2. Our “modal” description of choice-theoretic work is very much inherited from Charles Tilly’s notion of “standard stories.” But the same mechanisms associated with choice-theoretic work show up in other approaches. The difference is not the mechanisms per se, but how theoretical elements are put together in explanatory stories.

We deal with a lot of this in the actual article. Whether we are persuasive or not….

I’ll reread the article presently, then. As representations of research traditions or thematic modes of enquiry rather than of logically exclusive ‘paradigms’, the typology seems compelling to me. Well, as one colleague of mine observed, we’re so conditioned to 2x2s that it’s hard to ditch the niggling feeling that there should be another category ;)

More on the “clusters” which aren’t supposed to be (or become) tribal “isms”:

1. I doubt they will get as tribal as the isms. There’s good pol psych reasons why some issues are highly predictive of partisanship in general. The issues about actors and contexts in your typology are not like that at all.

2. The typology has the feel of something a bit more meaningful to sociologists than IRists (or polisci-ists), issues that they tend to like arguing about. No harm in that, but it may limit the appeal.

3. The typology itself doesn’t establish that ir theory is alive and well, bursting with “contentious conversations”. We really need direct evidence of such conversations (which I didn’t notice in the long version. Did I miss this evidence? )

4. I see the typology as a prescriptive thing: you would like to see the conversations directed to those particular contentions. That’s OK. One good thing maybe less heat and more light than other possible contentious conversations. But there are also other things IR should converse contentiously about not covered in the typology.

‘The typology has the feel of something a bit more meaningful to sociologists than IRists’

I would so very much like this to be a false dichotomy.

I think I said we’re all global sociologists now…:)

Your tribe of global sociologists bars us global biologists from joining. :-(

This doesn’t look much like *sociology*. It looks like *social theory*, which isn’t surprising as that’s the equivalent of *international theory* to IR. Even sociobiologists have to relate actors to social and cultural contexts.

“Sociobiologists”? First we were genetic determinists. Next you’ll be calling us Social Darwinists and Eugenicists. *sigh*

“Sociobiologists”? First we were genetic determinists. Next you’ll be calling us Social Darwinists and Eugenicists. *sigh*

“Even sociobiologists have to relate actors to social and cultural contexts.”

Even IR theorists and social theorists have to relate actors to social, cultural, and biological contexts.

Mine don’t. I see social life happening over at least four planes.

1 Material Transactions (which would include biology)

2. Intersubjective factors

3. Individual subjectivities

4. Social structure.

So you can join. Let me know where to send the membership forms. :)

Thanks! Looks like I’m being lodged in the basement along with the Marxists. Not the most welcoming of room-mates for us evil sociobiologists. I hope to colonize those nice-looking rooms in the superstructure too soon!

Colin, Colin, Colin ;-) We never said that the map should change to more accurately reflect the really real state of IR theorizing. Nor did we say that we think our map is a more accurate representation of the field. We said that this map answers the “end of IR theory” question by claiming that there is a way of viewing the field in terms of which IR theory is not at all at an end, but is instead thriving. So “the end of IR theory” is how the situation appears from one point of view, but not from ours.

I would also take issue with the insinuation or allegation that any kind of account of anything presumes a dualism of “thing” and “account.” As if it were meaningful to refer to a thing outside of all accounts of it. “A map of IR theory” to me means a way of ordering IR theory that is either helpful or not helpful, useful or not useful. That there are other ways of ordering IR theory does not, to me at any rate, imply that there is a thing called “IR theory” with an autonomous existence from its maps. Things are only things under a description, and more than that, well, “whereof I cannot speak, thereof I must keep silent.” Except perhaps to remind ourselves of the incompleteness of any description…My point is that there is a monist way of understanding mapping that does not require dualism. In any case, this is irrelevant to our argument in the piece, I think

Sorry Patrick, you know there;s no way I’m going to let you off that particular hook that you placed your self on…:). The dualism is implied in how you framed the issue: One example, but there are many others: ‘The problem, we argue, is that the mental maps of the field with which so many of us operate do not give pride of place to the theoretical points of contention that actually do unite the field by giving IR scholars a set of debates within and against which to locate their own scholarly work. The perception of excessive theoretical fragmentation is thus an artifact of the way we conventionally map the field, and accordingly, what has to change are our maps — not IR theory.’

And, of course, the one I really like, ‘we argue that international theory consists not of research design principles and philosophies of knowledge, but is instead scientific ontology: a catalog of the “stuff” of interest to the researcher and how it is interconnected.’ which is a direct claim about the nature of IR theory that you map attempts to grasp. So you are claiming a more accurate (maybe cashed out in terms of more utility, because I don’t know yet what the more ‘accurate’ means) account, you are explicitly, not implicitly saying in all these statement that only that the current ways of mapping have something wrong, but that yours is a better (more accurate) representation. That’s fine. I like that. I’m with you (only so far). If it’s not more accurate/better/more useful, and corrects some of the errors of the previous mappings, why should any of us care?

Likewise, how can any description be incomplete if there’s nothing outside of the description that it’s attempting to describe? Of course, we can only know things under certain descriptions, but those descriptions and the things they describe are spontaneously generated, or map directly onto each other (I wish). And as for Wittgenstein and remaining silent on what we can’t speak of, that’s not one of the brightest normative claims he ever made. Ludwig was good at the rhetorical flourish, but when you dig into that phrase it’s an awful conservative world view, that doesn’t propel us to question our categories, use of language and so on.

And finally, I’m still waiting for someone to answer the question; if the maps are descriptions of some terrain that is not distinct from the maps, why are they useful, and for who? Who is deciding utility here? More to the point, you’ve already answered this question even as you try and deny it. The current maps produce a perception of fragmentation when the field isn’t actually as fragmented as the maps suggest, and they fail to give pride of place to to the theoretical points of contention that actually (did use the word ‘actually’ isn’t it redundant – anyway, as you are always telling me the actually implies that there’s a way the field is that the current maps are missing) that is not captured by the current maps. And then you specify some new maps that you suggest are more useful because they correct these defects in the current maps.

Anyway, round and around we go. More to the point, how is Aber?

“if the maps are descriptions of some terrain that is not distinct from the maps, why are they useful, and for who?”

Perhaps we should extend the metaphor a little further; think it through a bit more. Semi-edited stream of thoughts ahoy.

What’s the use of a map that you can’t carry around in your hands or nail to a wall? It is the very separability of the map and that to which it relates that makes it a map. Borges’ infamous story was not just one of a map expanding to cover a territory but of a map *turning into* a territory. Once it could no longer be used as a map it ceased to be a ‘map’ in any meaningful sense and became what must be navigated (possibly with the aid of smaller, more useful maps).

Even those vast, warehouse-size war maps that the U.S. military use to visualise the territories they seek to dominate – the kind that generals and their minions use golf buggies to traverse – are clearly separate from the wide, open, mountainous, AK47-filled spaces to which they relate. Even the largest map must be severed from its referent territory in order to be a map.

Perhaps we should also recognise that there are many different kinds of maps. The Ordnance Survey map is a completely different beast to the London Underground map. Both very useful and, indeed, quite beautiful in their own ways – but different.

Is the OS map more ‘accurate’ than the underground map? Well, I’m happy to say that it’s more complex, detailed and that it serves a wider range of purposes but ‘accuracy’ can only be judged relative to a practical criterion: what’s it for? The underground map is entirely useless for, say, urban planning but navigating the underground with an OS map sounds like a recipe for getting well and truly lost.

Okay, so I’ve begged a question here: is accuracy equivalent to usefulness? For maps I think that it is. To say that the OS map is less useful for navigating the London Underground but that it is nevertheless more accurate would require a fixed standard of representativeness – Cartesian coordinates, linear perspective, a grid system, consistent distanciation – that the OS achieves but the UG map doesn’t. That seems to me to be a prejudice, nothing more.

When we say ‘accurate’ what we mean is ‘does it deliver me to the correct location?’ or ‘does it provide me with the information that I need?’ not ‘does it give me a holistic, eye-in-the-sky view of everything around me?’ A map that misleads us is not ‘accurate,’ regardless of its style and method of construction. The ‘leading’ is the important thing, not the degree to which it approximates an annotated aerial photograph.

So, if accuracy presupposes a purpose, what is the purpose of this ‘cognitive map’ of the discipline? Where are we travelling to?

Going back to my first point, I don’t accept that ‘separability’ as I describe it above necessitates a relationship of ‘duality’ between map and territory. Rather, it signifies plurality. E.g. when you’re navigating a metro system you may have the map in your hand, in your head, on your smart phone, etc. but there are also larger maps on the walls with ‘You Are Here’ written on them, there are signs everywhere, arrows pointing you in the right direction, etc. Where does the map end and the territory begin? For a well designed map *system* the line is blurred – and this makes the map more useful rather than less. The map is still plainly separate from the territory but it blurs into it rather than standing apart from it, other to it. Hence ‘plurality’ makes more sense to me than ‘duality.’

I suppose this begs more questions: are we talking about a map as a singular, isolated entity or a map system as a dispersed, integrated one? I think that any map can be spoken about plurally, relationally, as integrated. At the absolute minimum any map requires the cognitive competence to read it properly. That competence must have come from some prior experience, perhaps formal training, perhaps just generic childhood learning. Most maps also connect to ‘signposts’ of some kind placed around the territory that join them together.

These markers tie map to territory *and* territory to map. They lead the map-holder to where she wants to go but they also lead those wandering around the territory lost to the map-system – they nudge stray asteroids into orbit around an already defined formal idealisation.

So, a map always functions as a map in relation to other entities and this assemblage can become expansive and powerful. If the map depends on such entities in order to function then its ‘accuracy’ must be judged relative to these other things also. Every accurate map, every map that leads somewhere, does so through plural relations.

So, in addition to my above question (where are we travelling?) I suppose I also need to ask: What resources are we travelling with? What skills and additional materials can we presuppose? Can the line between map and territory be blurred in order to make the map *more* accurate?

Or does blurring the line increase accuracy in this case? It seems to me that cognitive maps *do* blur into the world *if they catch on*. At various points in time different people came up with terms like realism, neoliberal institutionalism, post-positivism, analyticism, etc. and then propagated them. The terms spread into the world as they were used in research papers, as they were taught to students, as they were used to title chapters of textbooks, as they came to categorise reading lists and library shelves, as people self-identified with them, as others used them as terms of abuse, etc. etc.

In other words, map and territory blurred together as the terms themselves became reified – dried out into stable referents.

This makes me wonder how we think about reification. It’s usually stated as a negative – ‘this term is reified, we need to destabilise it.’ But reification is a marker of success. The more numerous and densely populated its signposts become and the more these age, weather, patinate and fade into the background, the more this map is cemented not just in our minds but in our world. Does success denote legitimacy? Does might mean right? Is the preservation of tradition an end in itself?

What to conclude? Well, I think that we must periodically tear out our signposts and install new ones, for two main reasons: Solidified signification systems are power bases that are reinforced and bolstered not for their epistemic virtues but for the privileges they afford the powerful. Secondly, making ourselves temporarily lost gets us thinking again. Making our journey from A to B somewhat more difficult in the short term allows us the possibility to form new relations, chart previously unseen details and see already known locations in a new light.

So, regardless of this cognitive map’s *correspondence* to the world its novelty alone makes it worthwhile as it forces us to navigate our world slightly differently. It is not unrelated to previous mapping schemes – indeed it draws on them – but nor is it deferential to them. It doesn’t whirl us around so much that we lose all our bearings but nor does it simply reproduce common sense.

I suppose what we’re doing here is an exercise in signpost contestation. Signposts lead wanderers into the map-system as well as guiding map-holders about within that system. Thus nothing is innocent. However, we have to wonder about what degree of disorientation is desirable. Should we burn it all to the ground and start again or just rename a few streets here and there?

Whatever we do we are stuck with the necessity of ‘mapping’ in all its practical, plural, processual glory.

There endeth my exercise in brain emptying. I have no more.

Not much for me to disagree with there Philip, apart from to welcome you to the realist camp. Whether you take the leap into scientific realism is a different matter, but I think it’s at least implied here. Patrick to remain consistent has to deny that the ‘wide, open, mountainous, AK47-filled spaces to which they relate’ exist. I know, you’ll think: how can anyone seriously deny that? But, you know….I don’t have an answer to that one. Nor if monism is right do I have an question of ‘if we as a species disappear does the world go phut as well?’ Apparently for the monist the answer to that is yes. For PTJ there is no referent territory to map.

The underground map is also useless for cooking as well, so I hear, but it’s not meant to be a representation of cooking. I’d say it’s meant to be a representations of the relations between the stations and the lines, and as such it’s pretty accurate. If it wasn’t it couldn’t be used to navigate the underground.

Anyway, I agree about tearing out our sign posts (I also agree with what you say about reification), both of those reasons are valid but what Patrick and Dan are arguing is that there is another reason (one I endorse, but can’t reconcile with the commitment to monism), and that’s that the current maps are a distortion of the field (they get something wrong). That implies, I think, a commitment to the Maps being one way and the field being another; not giving pride of place to X, and portraying the field as fragmented when no such fragmentation exists.

Thanks, it’s nice to be here! I’m on the fence about scientific realism. Not so much that I’m undecided as that I feel that I have a leg dangling on either side. If it sounds painful, it can be.

Anyway, I like the map metaphor (as you can probably tell). I suppose Patrick and Dan’s argument that our current maps are a distortion of the field can be reworded as ‘our current maps, entrenched as they are, lead us down blind allies and distract us from more panoramic avenues.’ What are these alleys and avenues?

If we want to keep up the map metaphor and answer this question we have try and *use* our maps and see where we go astray – when do we get to where we want to go, when are we lost and frustrated? We can’t just go back to the language of vulgar correspondence theory and say abstractly that the map doesn’t ‘represent’ the territory because it doesn’t look much like it or because it distorts it in certain ways. As we’ve established, a map’s ‘accuracy’ can only be assessed in relation to its use in a particular practice – and a good map is often the least ‘faithful’ or straightforwardly mimetic.

So, where do we go astray? Where are the gaps and elisions? Where do things just not fit or feel right? What is the terra incognita of our existing maps? Where be our dragons?

(These are rhetorical questions, I’m not expecting answers on a postcard or anything.)

One issue that springs to mind for me is the assumption that theory necessarily simplifies things. On the contrary, some theory forces us to recognise more of the tangled relations that are caught up in international affairs rather than less. E.g. feminist theory, which actually makes things more complicated by bringing attention to the mostly ignored roles that women play in political life. Okay, perhaps it simplifies other things in order to do that but clearly the role of simplification isn’t simple.

The obsession with ‘policy relevance’ is another case. Some maps would suggest that the only real or legitimate research going on is the narrowly ‘problem solving’ kind that seeks to inform policy makers and allow them to better exercise their powers. That’s deeply tied into assumptions about political science, explanation, theory and so on as well as the place of public education and research within the neoliberal state.

What about producing knowledge for activists, for the general public, for academia itself or even, heaven forbid, for the benefit of students – giving them the best, most insightful, revelatory and transformative education possible? In fact isn’t this what most academics are working towards most of the time? A map that reflected this reality would make for a much brighter avenue or two.

And so on.

“I suppose Patrick and Dan’s argument that our current maps are a distortion of the field can be reworded as ‘our current maps, entrenched as they are, lead us down blind allies and distract us from more panoramic avenues.'”

So lets’s look at this for a moment. If our current maps lead us down blind alleys and distract us from more panoramic view. First, how do we know it’s a blind alley? Well a blind alley, in this context can either mean that its a ‘a mistaken, unproductive undertaking’ or an alley or passage that is closed at one end. Now I suppose, like Lake they could simply said that the ‘isms’ are no longer productive, but a blind alley implies not just something that is ‘unproductive’, but the further clause that the unproductive nature of the alley comes out of some mistake. So the current maps framed on the isms are getting something of the terrain wrong and turn us down a ‘blind alley’ that not productive in helping us navigate our way round the terrain. Apple maps would allow us to note this error in the map and get it corrected. Dan and Patrick are explicitly doing this; so I’m still maintaining that it’s reliant on the distinction between the way the current maps are configured and the way the terrain actually is, hence we need to change our maps to give us a more accurate mapping of the field (even the concept of a mistake implies something you are mistaken about). If Blind alley is interpreted as meaning a passage that is closed at one end, then that might be fine. One can say the ‘isms’ are a blind alley and leave it there, but as soon as you start adding, ‘hence we should move to a different typology’ (map) the assumption is this new map is going to give us something (that there is a better way), some alternative route that might avoid the dead end alley. So, even parsed the way you do, I don’t see how a dualism, and some level of accuracy about what the maps are representing is avoided. Essentially, I’m trying to establish some common ground so that we might actually have a discussion as to whether, why and how, the new J&N map might be an improvement on the old map (the isms). I think that common ground is already in the piece, but it’s predicated on a dualism (used positively, not negatively) and some version of realism in relation to the better accuracy of the J&N map over the isms, but I’m not sure P&D can accept that. I should add, although the map metaphor might be useful in some respects (and I’ve used it myself previously (https://philpapers.org/rec/WIGRE) there are other ways to think about these issuse; crosswords puzzles; legal cases, and so on. But like you, I like the map one.

Incidentally, it’s the ‘End of IR theory?’ The question mark is important. There’s also a way of viewing IR theory as a commentary on a game of football, or a series of cookery instructions, or a way of constructing a piece of origami, or a way of, I don’t know, add as required. But anyway, you are saying your piece gives us a view in which IR theory is not at an end, and the/some alternatives present us with a view that it is (it’s not btw, how could it be; I actually preferred the title ‘The end of theory?’). Now which is the better account and how would we tell?