This is a guest post from Brian J. Phillips who is a research professor at the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE) in Mexico City.

A number of studies in recent years have systematically examined terrorist groups, exploring lethality, longevity, and other outcomes. However, much of this research does not explicitly indicate what it means by a “terrorist group.” When definitions are offered, they differ considerably. These differences have empirical implications and matter for how we think about terrorism.

There are a number of types of definitions of terrorist groups, and related criteria for gathering data sets: Some scholars, such as Blomberg and colleagues, basically include any organization that has used terrorism. At the other end of the spectrum are definitions that only include groups primarily using terrorism as opposed to other tactics. Cronin’s book on terrorist group defeat is an example. Sánchez-Cuenca and De la Calle also employ a restrictive definition, suggesting that terrorist groups are those that do not control territory.

In the middle of the spectrum are fairly inclusive definitions, stating that any subnational political group that uses terrorism is a terrorist group. Some studies with this middle-of-the-road definition are Carter’s study of state sponsorship, Jones and Libicki’s study of terrorist group failure, and my own work on alliances between terrorist groups.

Why might these different definitions matter?

There are theoretical reasons, and of course we want our concepts to be meaningful. Another important issue is that conceptualizations and measurement can affect results.

A comparison of terrorist group data sets shows that there are indeed substantial differences in dependent variable values across data sets. These differences seem to be related to the conceptualization and measurement of “terrorist group.”

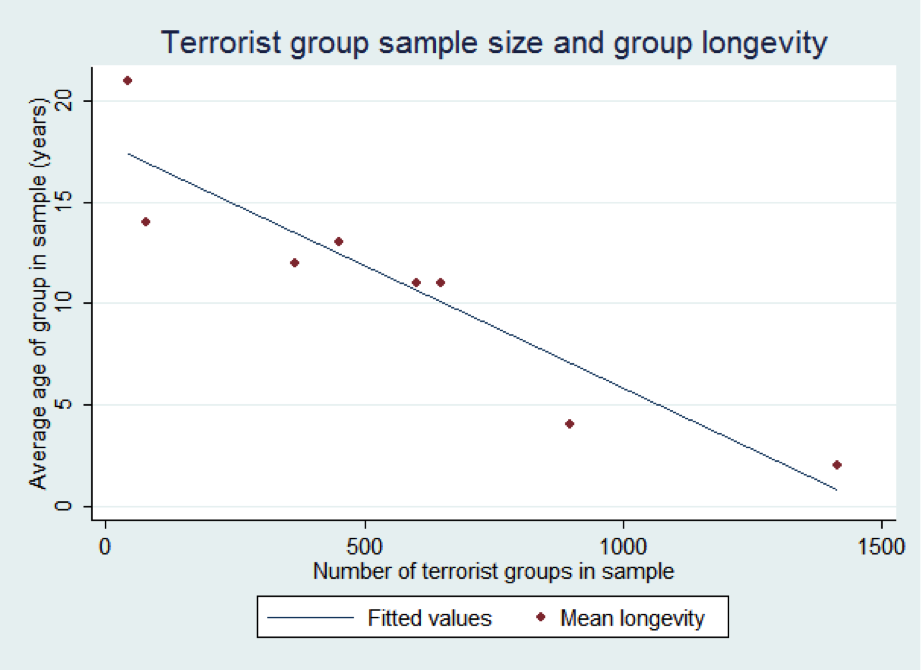

The graphic below uses metadata on nine studies of terrorist group longevity, explained in this article. In several of the data sets, the average group survives around 11 years. However, in one data set the mean group survival is 21 years, and in another the average group only lasts 2 years.

Average group survival appears to be negatively related to sample size. The smaller the sample of terrorist groups – for the most part, the narrower the definition employed – the longer the lifespan of the average group.

One reason is that the larger samples include many “one-hit wonder” groups, and others that didn’t last very long. On the other hand, the smallest sample, the U.S. Foreign Terrorist Organization list (mean group survival of 21 years), has very specific criteria for inclusion. This results in a list of quite durable groups, an unusual sample.

The apparent pattern in the figure raises a number of questions. Does the conceptualization or measurement of “terrorist group” affect research conclusions in nontrivial ways? Do similar patterns occur in studies of organizational lethality or other outcomes? Beyond empirical questions, are we theorizing and measuring terrorist groups as well as we should be?

Answering all of these questions would take more space than a typical blog post allows, but here are a few thoughts on how research conclusions might be affected. Regarding studies of group longevity, smaller samples containing especially durable groups might be biased toward null findings or understated effects. This is one issue Geddes discussed regarding case selection. Most of the durable terrorist groups have various shared characteristics – large memberships, alliances with other groups, perhaps state sponsorship – so these factors might not appear to be substantively important for survival in samples of these especially long-lasting groups. Including more short-lived groups in a sample would probably make the importance of these variables more clear. Similar biases perhaps occur in studies of group lethality or propensity for using suicide attacks – especially when the most data exist on especially lethal groups and those that use suicide attacks.

Some of the challenges of terrorist group samples come not only from definitions, but also from the difficulty of gathering data on clandestine organizations. We have don’t have as much data on short-lived and small terrorist groups.

Finally, it is worth acknowledging that this post sidestepped the question of the definition of terrorism itself. Important debates on the concept of terrorism continue, as is suggested by a recent Jarrod Hayes post on the Duck.

Overall, thinking more about these issues could substantially contribute to terrorism studies (which is said to have some room for improvement), and the broader field of political violence.

As with any concept, it is important to consider how conceptualization and measurement can affect the sample used, variable values, and above all the inferences drawn.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments