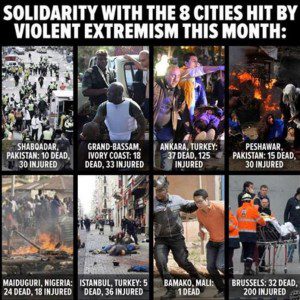

I was among those last week, after hearing about the events in Brussels, who tweeted or Facebooked in solidarity with Belgium… but also in solidarity with civilians killed in Ankara, Baghdad, Yemen, later that week Cote d’Ivoire and (as of yesterday) in Lahore, Pakistan. I took some flak for this on Twitter and in my personal email. Why can’t we just focus on Belgium on a week like this? some people ask? Don’t you care about this country and its allies? they say. I do, of course, but I also care about accuracy in my contributions to the media discourse, and about not helping the terrorists.

I was among those last week, after hearing about the events in Brussels, who tweeted or Facebooked in solidarity with Belgium… but also in solidarity with civilians killed in Ankara, Baghdad, Yemen, later that week Cote d’Ivoire and (as of yesterday) in Lahore, Pakistan. I took some flak for this on Twitter and in my personal email. Why can’t we just focus on Belgium on a week like this? some people ask? Don’t you care about this country and its allies? they say. I do, of course, but I also care about accuracy in my contributions to the media discourse, and about not helping the terrorists.

The problem with an over-focus on European victims of DAESH-inspired terrorism is that DAESH then looms larger as a threat to the West than it actually is to anyone. The attacks in Belgium weren’t Muslims against the West: they were DAESH against the world – as evidenced by the fact that DAESH targets more Muslims, and more people in Muslim majority countries, than Westerners. Victims of indiscriminate violence everywhere deserve our sympathy, solidarity and support – whether killed by suicide vests or aerial bombs.

But, does this mean we should be tweeting / posting about DAESH-sponsored attacks in Pakistan, Ankara, Baghdad, Grand Bassam, as often as we in the West post about Belgium? At first I think I was buying that, but after more thought actually I would say the opposite: we should tweet about Belgium, or attacks here in the West, about as often as we post/tweet about specific terror attacks in Pakistan, Turkey, Iraq, Syria and Cote d’Ivoire: That is, sparingly.

And the reason we should do this is so as not to feed the trolls. That is, the terrorists.

Terrorism is all about media attention. To work, terrorism must generate fear beyond its targets, and fear is amplified when it goes viral. And that viral media attention (including social media attention) makes terrorism look a lot more prevalent than it really is – as Nicholas Kristof reminds us – in the scheme of things. When we fill our feeds with a constant barrage of terror attack news – which will only be exponentially greater if we seek to be more inclusive – we highlight terrorist activity to the exclusion of far more important trends happening in the world.

That’s not a popular view. “Easy for you to say,” some people will write me, “Your town wasn’t just attacked.” So let me be clear: I have as much skin in the “protection from terrorists” game as anybody – because the aim of terrorists is not just to kill people but to terrorise those watching.

And I am terrified. I am mother to an elite soccer player who travels internationally. I just put him on a plane this weekend to a soccer tournament abroad, and he’ll be traveling again – to Europe – with his team in just a few weeks; then again, this summer; and constantly, really for the rest of his childhood. I think about my child all the time right now when I read stories of terror abroad. That the attacks in Belgium targeted airports did nothing to make me, as a mother, feel safe packing my child off unaccompanied on an international flight no matter where he’s headed.

But it was the news out of Baghdad this week that hit me the hardest: a suicide bomb killed 60 and wounded over 100 at the end of a soccer match, in a stadium, as trophies were being handed out. I can picture myself there. I can picture my son, receiving his trophy one minute and obliterated or worse the next. My heart aches for those families as surely as they ache for those who lost loved ones in Brussels. I cringe at the pointlessness of it all.

Am I afraid? Absolutely. I’m also angry. But instead of acting on those feelings, I choose to remind myself that they are both natural and overblown, and that giving in to them means DAESH wins.

What helps me do that is to keep my mind on the odds:

- According to the US State Department, my son’s greatest risk of death when traveling abroad isn’t from terrorists, it’s by far from car accidents.

- According to the Global Terrorist Database, my son’s greatest risk of death from terrorists in Europe, even in the age of DAESH, is down significantly from what it was in 1988.

- According to the Economist (crunching Interpol numbers), my son’s greatest risk of death from terrorists in Europe doesn’t come from DAESH or any other so-called “jihadist” terrorist group, rather it comes from secular separatist terrorism.

- BUT, according to Snopes.com, fact-checker of Internet memes, my son is still far likelier to be shot by a toddler here in the US – or crushed by furniture – than he is to be killed by a terrorist here, traveling in Europe to a soccer game, or anywhere else in the world. And that is what I remind my son when he watches the news. Terrorism is scary, but unlikely in any given place and time.

You know what probably does increase the risk of DAESH-sponsored terrorism? Strengthening DAESH by over-reporting DAESH-inspired incidents, thus fanning the flames of terror.

That’s what DAESH wants. It makes them feel big, scary, significant. It earns them recruits. It increases fear of Muslims by Westerners, which fuels policies foreclosing escape routes from DAESH-controlled areas, thus raising DAESH’s tax revenue. And that’s what people do when they make a spectacle of DAESH’s terror events to the exclusion of all else, slap “State Department Travel Warnings” on entire regions based on super-low-risk anomalies, declare all-out war on Muslims like some would-be politicians to whose remarks I refuse to link. All this makes my son less safe by increasing the reach and power of DAESH by spreading fear of what they do.

What limits DAESH’s power and makes my child – and your children – safer? Doing what I do (and what Juan Cole recommends): recognizing that we and most Muslims are in the anti-DAESH fight together, speaking in solidarity with DAESH victims everywhere, and generally pointing out that these attacks demonstrate DAESH’s weakness, not its strength.

It’s possible to do all that, in solidarity with the families of those who lost their lives in Brussels. And Ankara. And Lahore. And Baghdad. While choosing to focus equal attention on other threats to civilian life by non-natural causes in the world today. Like indiscriminate aerial warfare by our allies (which also fuels violent extremism and which actually can be reduced rather than increased by shining a media spotlight). Or like the proliferation of small arms abroad and in the United States. Like car accidents.

So rather than looking for news stories of terror incidents from other countries to post on Facebook in some kid of equity with posts about Brussels, I will leave comments of solidarity on the threads to those stories, but on my own Facebook and Twitter feed I will post news instead of ways in which people are working across religious divides to make the world safer for all civilians.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

I just want to note that several of these attacks were not committed by DAESH (Cote d’Ivoire, Mali, Nigeria, Pakistan). While the point still stands, it’s important to remember that there are multiple extremist groups that have various grievances against the countries where they’re committing the attacks, as well as in some instances against the West. They’re not one massive Muslim extremist group, which makes them out to be bigger and more powerful than they really are. Some groups have linkages, but some are fragmented or are in a struggle against others.

Firstly, please immediately remove the image displaying dead bodies and casualties of the Istanbul attack. I can’t fathom why you have posted that. Please, just remove it.

Secondly, I see what you are trying to do here. It’s a common point, of course, not to ‘feed’ groups who carry out terrorist acts. But, let us be clear, it’s a very questionable proposition. It is questionable because your view of the these groups and their motivation are bizarrely apolitical. Terrorist attacks will *not* stop if they are not reported. They will continue. This is self-evident if you look at the countries which deliberately censor reporting on terrorist acts (China, the Middle East itself, etc.). While it is nice that you talk about looking for “ways in which people are working across religious divides to make the world safer for all civilians” I would strongly suggest that as a political scientist/IR person you begin by looking into this politically and realising that halting US and European interference in the Middle East is the only way to stop terrorist attacks in the future. The way you present it here negates all discussion of that possibility. There will continue, however, to be terrorist attacks as long as this issue is not dealt with in explicitly political terms.

James, do you mind me asking why you object so strongly to the image of the dead in Istanbul? (Is it some sort of cultural taboo? Is there a political reason?)

James, Like J.D. I was also curious why you were so bothered by the image. I am going to keep the screenshot because it’s an artifact from FB that captures the kind of discourse I’m critiquing, but I’ve also shrunk it so perhaps it’s not as in-your-face.

Your second point is well-taken. I don’t know of a study that really tests the hypothesis that media attention strengthens terrorist organizations. I’ll look for one, and you’re absolutely right that we should test all our own assumptions. Whether or not that connection is real though, I think it’s fair to say that media coverage drives terror itself. That is, I may not be able to reduce future attacks by ignoring DAESH, but I can reduce the impact of their actions on the everyday lives of people beyond the kill zone by refusing to fixate on it. Which is good for my own mental health as the mother of a jet-setting American athlete, but also good, I think for society.