At a press conference on Sept. 20, 2011 Senator Susan Collins (R-ME) displayed a postcard. It was signed only “An Army Soldier.” She read the postcard aloud. “I will still be deployed in Afghanistan on 20 Sept. when DADT is finally repealed,” it read. “It will take a huge burden off my shoulders – a combat zone is stressful enough on its own. Thank you for your courage to vote in favor of repeal as a Republican. I will repay your courage with my continued professionalism.”

The repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell (DADT), the discriminatory policy that prevented lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) members from serving openly in the US military, had taken effect at 12:01am that morning. Collins was a leading advocate and one of only eight Republicans that had voted for the repeal. “This touches me so much,” Collins said. “It is so poignant that he could not sign his name. He had to write an army soldier and today he can sign his name and that makes all the difference.”

Tracey Hepner recognized the postcard. It was one of Rainbow Ribbon’s. As a military partner in a same sex relationship, Hepner had founded Rainbow Ribbon to give LGB military members and their families a voice in the debate over the repeal of DADT. One of the greatest challenges of the repeal effort was that while its military opponents were free to advocate openly against it, coming out in favor of the repeal as a uniformed service member could raise suspicions about one’s own sexuality and make one vulnerable to accusations of “telling.” Disclosing themselves as gay counted as homosexual conduct under the policy and provided grounds for dismissal. Even straight service members who favored the repeal put themselves at risk by advocating for it.

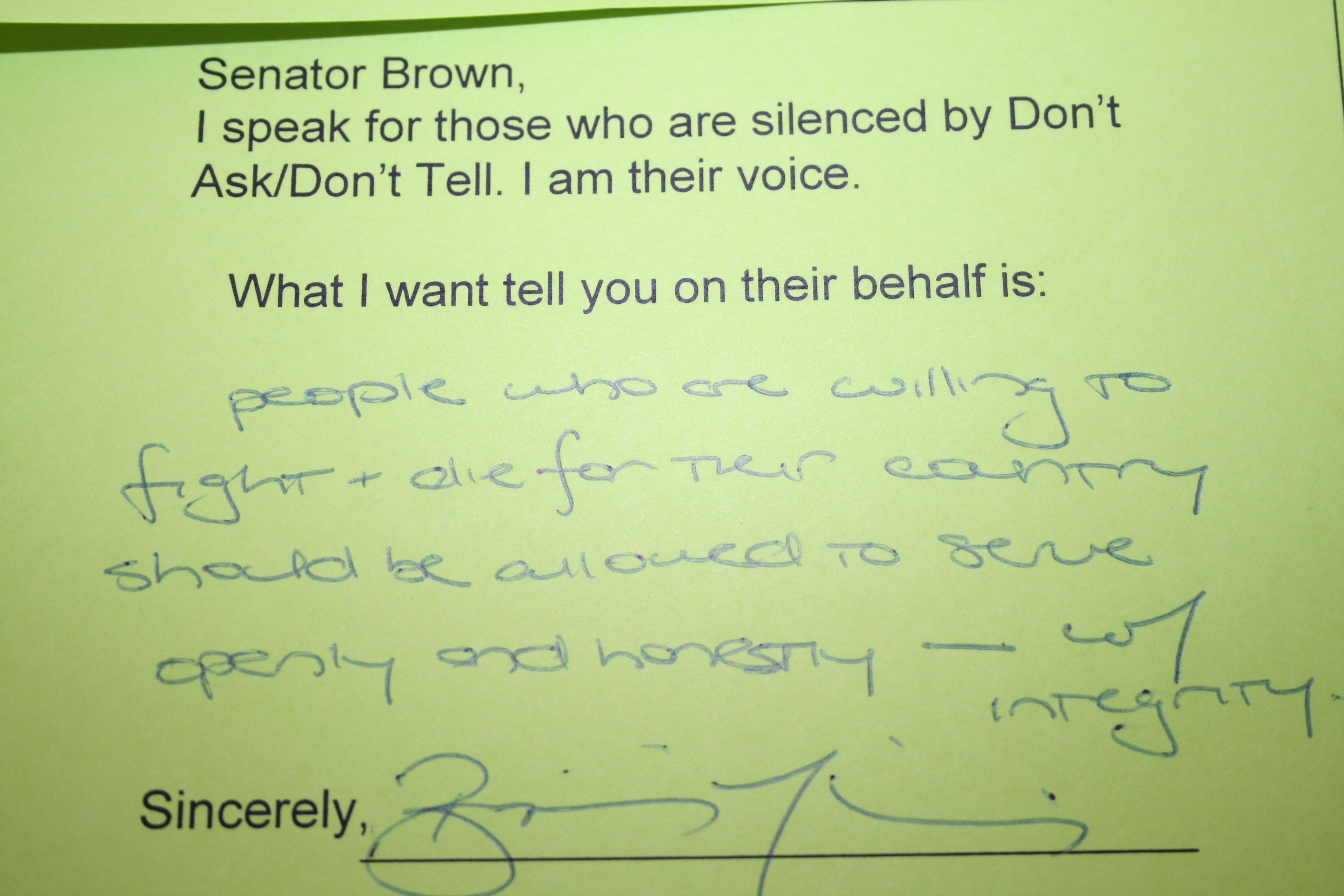

Hepner wanted to become more active in the repeal effort, but felt unable to out herself for fear of revealing her relationship with then Col, now Major General (ret) Tammy Smith. Hepner founded Rainbow Ribbon in 2009 with the help of allies who agreed to be the public face of the organization. She organized a postcard campaign, updating vintage designs with DADT repeal messages, facilitating communication between LGB active duty service members and Congressional offices.

Rainbow Ribbon postcard to Senator Brown. Photo courtesy of Maj Gen (ret) Tammy Smith

Meanwhile, in the Pentagon, members of the working group tasked with carrying out a comprehensive review of the impact of a repeal of DADT on military readiness faced a similar dilemma. Understanding what LGB military members and their families wanted was key to understanding the potential effects of a repeal, but LGB service members couldn’t speak about their wants or desires without violating the policy. In Sept. 2010 the working group reached out to LGB military families, including Hepner, with an invitation to the Pentagon. Hepner asked the 10 families affiliated with Rainbow Ribbon to join her. “I contacted everyone we knew and no one would go,” Hepner remembers, “so I said to Tammy, maybe I shouldn’t go. She said, ‘No. You have to go.’’

On the day of the meeting Hepner arrived in the visitor center of the Pentagon where she joined a group of 11 other LGB partners. It was a diverse group: partners of enlisted and officers from senior and junior ranks, different races and genders. Hepner didn’t know anyone in the group. Some had arrived with lawyers. They were all escorted upstairs to a conference room. “I was certain that everybody knew that we were the gay ones” Hepner recalled. “It was just my own paranoia.” The conference room was packed. Behind the table two more rows of chairs lined the walls. “It was kind of nerve wracking,” Hepner remembers. “The very first thing they told us was that the attendance roster would be destroyed and nobody would ever discover what we said in the room. Everything was only privy to the people in the room, but there were all those people in there.”

Hepner was the first to speak. She presented the information she had collected from the ten Rainbow Ribbon families who had responded to questions she had sent them. How many deployments had they been through? How many children do they have? But, what the officials wanted to know was what the families wanted. “We wanted DADT be repealed,” Tracy said. “But they wanted to know what else we wanted. But that’s all we wanted. They asked if we wanted to live on post, but how do we know?” Hepner wondered. “Under DADT we couldn’t be out to the military community, but we couldn’t be out to the gay community either. I wasn’t a subject matter expert in either.”

Like flipping a light switch, on the day the repeal of DADT was implemented LGB military members went from hiding in the dark to having their world fully illuminated. Suddenly not only could people recognize them for who they were, but they could also recognize one another.

One of the most important, yet unintended outcomes of that Pentagon meeting Hepner attended was that it expanded connections among LGB military families. Six of the twelve people who attended kept in touch and together founded the Military Family and Partner Coalition (MFPC), an all volunteer group of LGB military families. After the repeal, MFPC worked with existing military family support organizations to create routes for LGB families to access these organization’s resources. (MFPC has since merged with other LGBTQ+ organizations to form the Modern Military Association of America.) The day after the implementation of the repeal MFPC hosted a public ceremony and celebration at the Women’s Service Memorial in Washington DC. “We were invisible,” one of the speakers said. “We were silent partners unknown to one another. Today we would like to use this occasion to introduce ourselves.”

Another effect of the illumination was that it shone a light on the gendered effects of DADT. The most rancorous parts of the debate about DADT revolved around the homophobic fears of straight men who objected to deploying in close quarters with gay colleagues. Yet, the reality of DADT, and the prior ban on homosexuals in the military, was that it had a disproportionate impact on female service members—gay and straight. Accusations of being gay were routinely leveled at women regardless of their sexuality, aided by the fact that telling was interpreted expansively. Homosexuality included not only “any bodily contact, actively undertaken or passively permitted, between members of the same sex for the purpose of satisfying sexual desires” but also “any bodily contact which a reasonable person would understand to demonstrate a propensity or intent to engage in an act [of homosexuality].” Women–and racial and ethnic minorities–were consistently discharged at higher rates under DADT than their straight, white, male colleagues.

On the day of the repeal Maj Gen (ret) Smith, recalls waking up at Bagram Air Base feeling just as she had said she would in her postcard to Senator Collins. “I felt as though the weight of the world had been lifted off my shoulders,” she remembered. On her way to the chow hall, she secretly hoped to catch the eye of someone else who was feeling the same way that morning, but she didn’t: “It was like any other day in the Army, as it should be.” After breakfast she raised a flag in honor of the occasion. Today she and Hepner display it in their home in a wooden flag box engraved with the date, “9/20/2011,” and the words “honor, sacrifice, equality.”

0 Comments