A few weeks ago Facebook unleashed its new Terms of Use on the unsuspecting user community. As anyone with a FB site knows, though the changes were touted as enabling greater user control over personal information, FB’s new default settings enabled “Everyone” to view users’ information unless users were savvy enough to update their settings – a change that caused the Electronic Privacy Information Center to file a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission.

A few weeks ago Facebook unleashed its new Terms of Use on the unsuspecting user community. As anyone with a FB site knows, though the changes were touted as enabling greater user control over personal information, FB’s new default settings enabled “Everyone” to view users’ information unless users were savvy enough to update their settings – a change that caused the Electronic Privacy Information Center to file a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission.

Even worse, FB initially included profile pictures and friend lists as “public” information that could not be made private even by savvy users – a move so blatantly in violation of privacy rights that it quickly resulted in an outcry on web-pages like “Facebook Restore My Privacy Rights.” (Facebook quickly “tweaked” the options to make it possible to hide one’s friend lists, though it is unclear to me whether this would protect people whose friends have their lists visible to the world.)

Not all agree that these changes are worth the uproar. A joke going around on Facebook belittles the concern: “If you don’t know, as of today, Facebook will automatically start plunging the Earth into the Sun. To change this option, go to Settings –> Planetary Settings –> Trajectory then UN-CLICK the box that says ‘Apocalypse.’ Facebook kept this one quiet. Copy and paste onto your status for all to see, if we survive.”

I’m with those who see the civil liberties implications of these changes as troubling and significant. My concern is not so much with the changes themselves but the inability of users to opt out of them. I fear the genuine real-world conflicts between online expression and physical security – the young student stalked by an angry ex-lover, the dissident persecuted by her government.

But the row over Facebook’s privacy rules is not just about civil liberties. It’s also about the very constitutive rules governing the construction and presentation online social identities. People really do see their pages as online versions of themselves – avatars if you will – not necessarily reflections of their whole real-space being, but an online representation constructed in relation to a particular community of friends that simply becomes socially dysfunctional when forcibly shared with everyone.

And the evidence of this is emerging in online practice. Consider the growing popularity of Facebook “Suicide” websites like Seppukoo.com, which offer Facebook users a ritual means by which to exercise “exit” under the rubric of “reclaiming your offline identity.” According to Kaliya of Identity Woman.net:

And the evidence of this is emerging in online practice. Consider the growing popularity of Facebook “Suicide” websites like Seppukoo.com, which offer Facebook users a ritual means by which to exercise “exit” under the rubric of “reclaiming your offline identity.” According to Kaliya of Identity Woman.net:

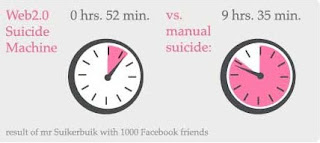

The Web 2.0 Suicide Machine offers “suicide” for Facebook, Myspace and Linkedin. It highlights its time saving nature taking just under one hour vs. over nine hours to go through the process manually with 1,000 Facebook friends. Their FAQs are great:

“If I start killing my 2.0-self, can I stop the process? No!

If I start killing my 2.0-self, can YOU stop the process? No!

What shall I do after I’ve killed myself with the Web 2.0 suicide machine? Try calling some friends, talk a walk in a park or buy a bottle of wine and start enjoying your real life again. Some Social Suiciders reported that their life has improved by an approximate average of 25%. Don’t worry, if you feel empty right after you committed suicide. This is a normal reaction which will slowly fade away within the first 24-72 hours.

Why do we think the Web 2.0 suicide machine is not unethical? Everyone should have the right to disconnect. Seamless connectivity and rich social experience offered by web2.0 companies are the very antithesis of human freedom. Users are entraped in a high resolution panoptic prison without walls, accessible from anywhere in the world.”

Whatever you think about the bleak humor of a Facebook “suicide, those who’ve left – or are thinking about leaving – are talking about their decision in terms of freedom.

Facebook has responded to Seppuko.com with a cease and desist message – interestingly, in the name of the privacy rights of its users. Seppukoo.com issued a reply shortly before Christmas.

The suicide metaphor suggests this is not simply the civil liberties of users at stake, but people’s entire sense of whether an online “life” separate from their physical lives remains “worth living.” I don’t know about this narrative of inherent dysfunction between one’s online and offline representations. I like both. We all have different masks we wear in different contexts; a networked expression of ourselves online is no different and is a uniquely functional means of remaining connected in a world where social distance has shrunk while geographic and physical barriers remain wide.

Without user choice over what can be shared with whom, however, and without clear-cut rules intelligible to a reasonably literate user community, those identities will become as bland as people’s professional websites. Who will post interesting personal pictures, or even their faces at all, on their profiles if anyone in the world can view them? Who will say anything funny, if everyone in the world must be counted on not to get offended at the joke? Friend lists take on a completely different meaning if in order to avoid awkward conversations with visibly excluded peers they get constructed not based on a user’s preference, but based on one’s estimate of people’s perception of those preferences as a visible part of their public profile. This not only constrains choice but the very social structure in which online identity construction occurs. It demands, indeed, the death and remaking of existing identities to conform with new rules.

No wonder users are up in arms. I hope users keep the heat turned up on the architects of Facebook and other social networking utilities, rather than pointing the gun at their online selves. EPIC is continuing to press the FTC not only to restore user choice but to make the default settings err on the side of privacy rather than openness.

And as of they this week they can do so by keeping close tabs on Facebook’s job search for an “Advertising and Privacy Counsel,” the job description for which is to “ensure compliance with advertising and privacy laws.” Readers interested in applying can read the job requirements here, which include not only a JD, state bar experience, and experience in privacy issues, but also “a sense of humor.”

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

0 Comments