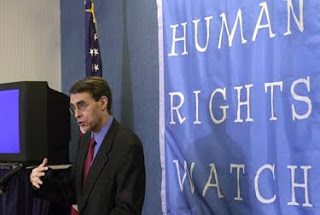

Human Rights Watch founder Robert Bernstein lit a fire under human rights activists yesterday with his NYTimes op-ed yesterday, criticizing the organization for its focus on Israel rather than more autocratic regimes in the Middle East.

Human Rights Watch founder Robert Bernstein lit a fire under human rights activists yesterday with his NYTimes op-ed yesterday, criticizing the organization for its focus on Israel rather than more autocratic regimes in the Middle East.

His argument is really about organizational mandate and issue selection: faced with the need to select among the many abuses competing for intention, how should a group like Human Rights Watch prioritize its activity? Bernstein argues it should focus on closed societies, not open ones:

At Human Rights Watch, we always recognized that open, democratic societies have faults and commit abuses. But we saw that they have the ability to correct them — through vigorous public debate, an adversarial press and many other mechanisms that encourage reform.

That is why we sought to draw a sharp line between the democratic and nondemocratic worlds, in an effort to create clarity in human rights. We wanted to prevent the Soviet Union and its followers from playing a moral equivalence game with the West and to encourage liberalization by drawing attention to dissidents like Andrei Sakharov, Natan Sharansky and those in the Soviet gulag — and the millions in China’s laogai, or labor camps.

Human Rights Watch issued a rebuttal yesterday:

Human Rights Watch does not believe that the human rights records of “closed” societies are the only ones deserving scrutiny… “Open” societies and democracies commit human rights abuses, too, and Human Rights Watch has an important role to play in documenting those abuses and pressing for their end.

To some extent this debate hinges on a tricky distinction between human rights law and humanitarian law. Human rights law governs what a state may do to its own people; since the movement has typically focused on civil and political rights, it makes sense to pay greater attention to non-democracies whose very governing structures violate the rules, than flinging barbs at violations on the margins of already free, democratic societies.

But humanitarian law governs what a state may do to the enemy in time of war, and it is humanitarian law that is relevant to the reporting on Israel that Bernstein is primarily addressing, as well as much reporting on the US. With respect to IHL, this distinction (if valid at all) breaks apart entirely, as the openness of domestic institutions has little bearing on the record of countries in war: militaries of democracies are no less likely to abuse noncombatants in time of war. In fact, Alexander Downes has found they may be more likely to do so.

In short, whatever the merits of Bernstein’s argument with respect to human rights (further picked apart by Michael Yglesias) it pretty much falls apart completely for IHL.

I think the tension Bernstein points to highlights HRW’s tenuous position at the interstices of two separate networks – human rights and humanitarian law. As Stacie Goddard points out in a recent study, betweenness of this type positions an actor to play a useful brokering role in international society, contributing to the development of new norms and ideas, and also increasing one’s influence within and between networks. However this latest PR snafu also highlights the disadvantages of being caught between two worlds with two different standards for human security agenda-setting.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

0 Comments