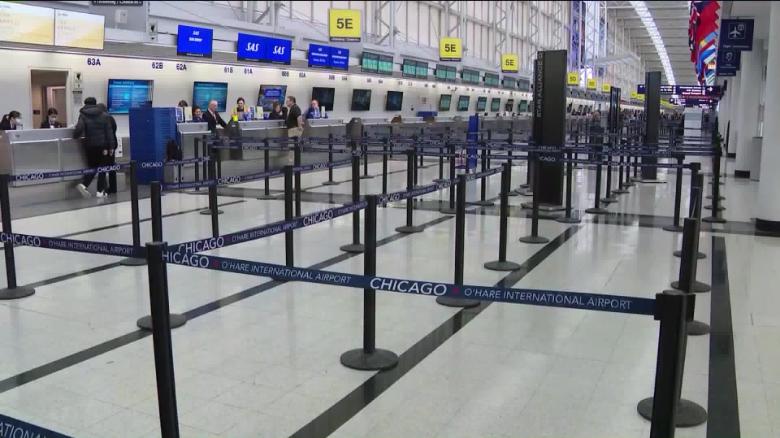

With the coronavirus taking hold, conferences being cancelled (I'm looking at you ISA), and college campuses like Harvard shuttering or going online, the coronavirus outbreak has gone global and upended countries and markets around the world. The worst may be yet to...