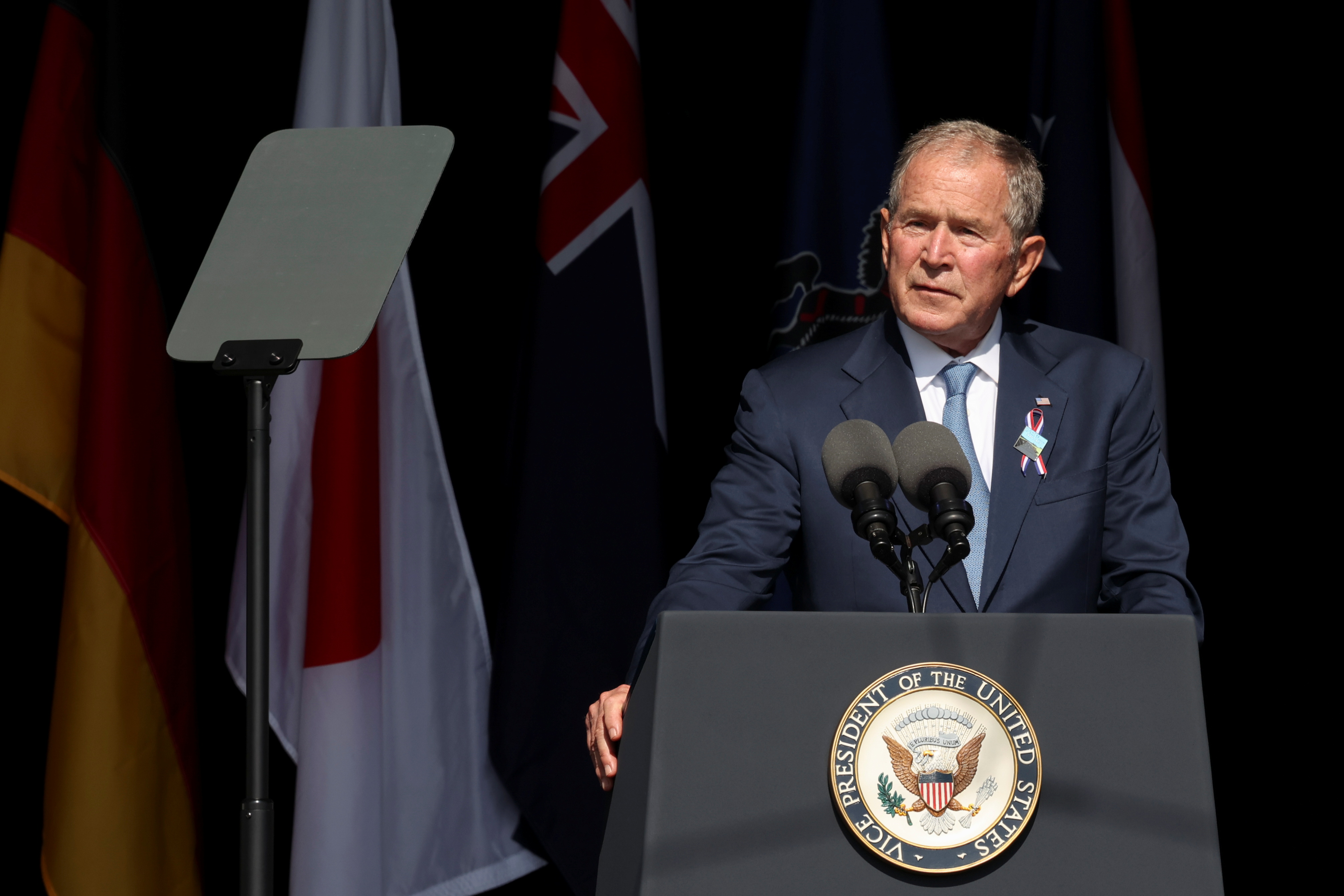

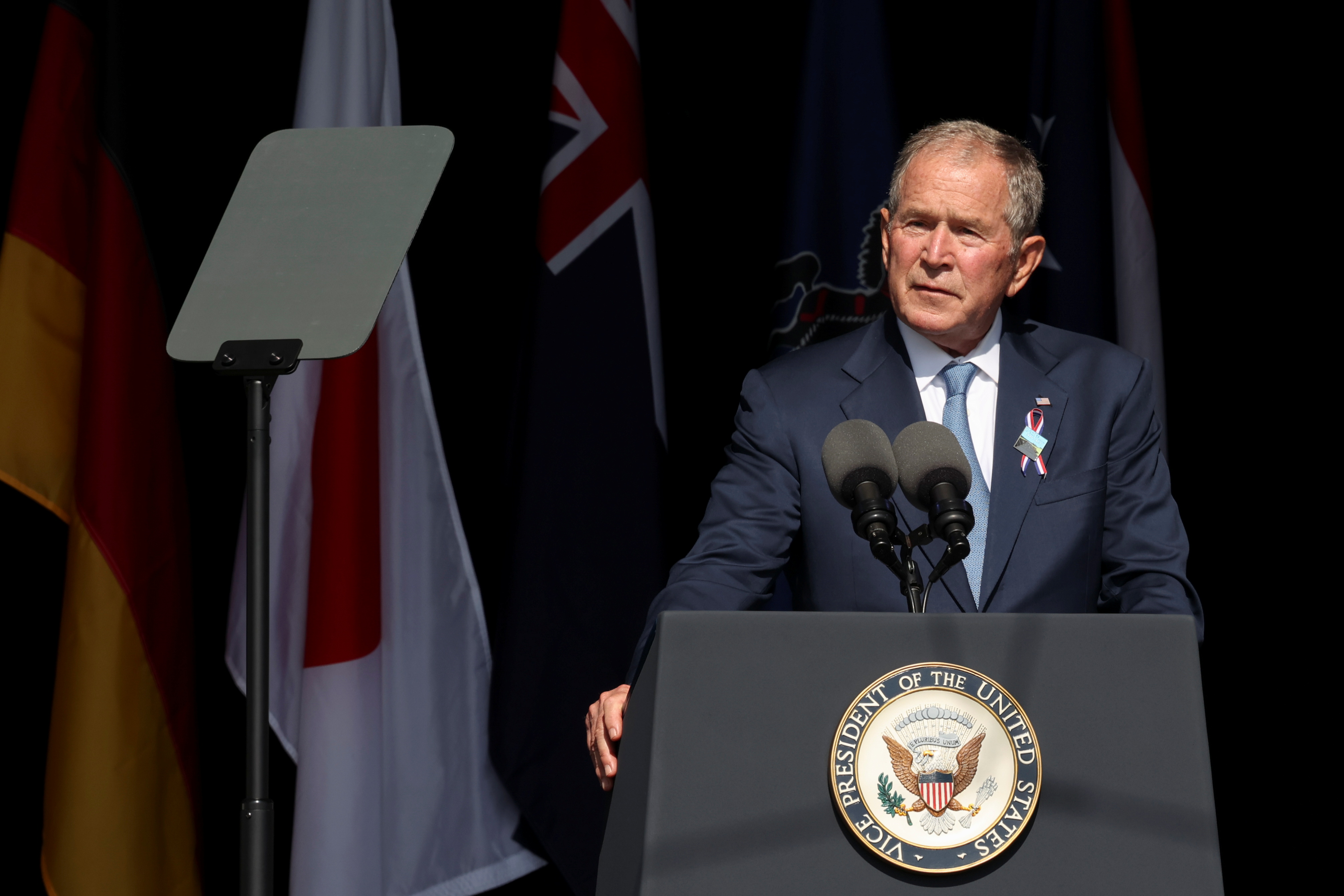

Numerous pundits have lamented the that Americans have not responded to the Covid pandemic with the unanimity they demonstrated after 9/11. But do we really want to return to the post-9/11 era of emergency consensus?

Numerous pundits have lamented the that Americans have not responded to the Covid pandemic with the unanimity they demonstrated after 9/11. But do we really want to return to the post-9/11 era of emergency consensus?

If border closures are stopgaps that are costly and potentially illegal, then countries must explore additional options for dealing with infectious diseases.

As an American living in London, I wake up every morning and check statistics: the number of positive cases reported the prior day in both the UK and US, the number of deaths, hospitalizations and...

This is a guest post from Courtney Burns and Leah Windsor. Burns is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bucknell University. Windsor is a Research Assistant Professor in...

In Marvel comics and movies, Ant-Man is a super-hero who can change his size using a special suit and "Pym particles." When giant, he's...giant. But when he's tiny he keeps the same density as a regular human, giving him the ability to lift and move things much bigger than his insect size. The idea of shrinking in size but having to shoulder the same--or greater--burden resonated with me, and in a way feels like a metaphor for the modern professor. This thought came to me in response to a recent email from my university. We have a hybrid set-up, with some students attending courses remotely...

This is a guest post from Tana Johnson, an Associate Professor of Public Affairs and Political Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her publications include the book Organizational Progeny: Why Governments Are Losing Control over the Proliferating Structures of Global Governance. COVID-19, which disregards national borders and threatens all countries, is a “problem without a passport.” The usual prescription is to 1) work through international organizations (IOs), 2) collaborate on collective long-term solutions, and 3) defer to experts. Yet in 2020, countries defied...

This is a guest post from Walter James, a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at Temple University with an interest in comparative political economy of financial regulation. The Federal Reserve has stood as a bulwark between COVID-19 and another Great Depression in the United States. But it must tread carefully to maintain its reputation and legitimacy once the crisis passes. Since COVID’s arrival in the United States, the Fed has acted with unprecedented speed by cutting its federal funds rate to close to 0%, purchasing massive amounts of securities, providing dollar...

This is a guest post from Alexander R Arifianto (Twitter: @DrAlexArifianto), a Research Fellow with S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His research focuses on contemporary domestic politics and political Islam in Indonesia. Nearly six months after the first case of coronavirus was first diagnosed in Indonesia, the country is in the midst of its largest public health crisis in history. As of August 3rd, about 113,000 Indonesians are confirmed to be infected and 5,300 have died from the illness. Indonesia is currently ranked the...

This is a guest post from Jennifer Mustapha and Eric Van Rythoven. Mustapha is an Assistant Professor at Huron University College in London, Ontario and studies the politics of the War on Terror, globalization and development, and Southeast Asian regional relations. Rythoven teaches International Relations and Foreign Policy at Carleton University, Canada. His work has been published in Security Dialogue, European Journal of International Relations, and Journal of Global Security Studies, among others. For many observers America’s catastrophic response to COVID-19 is a far-off spectacle...

Courtesy of US Navy, used under Creative Commons license. This is a guest post by William Akoto, a postdoctoral researcher jointly appointed at the Sié Chéou-Kang Center for International Security & Diplomacy at the Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, and the One Earth Future Foundation. In the fall, he will begin a tenure-track appointment at Fordham University. As people have become consumed with concern about the coronavirus, organized cyber criminal groups are actively exploiting uncertainty, doubt and fear to target individuals and...

This is a guest post from Julie VanDusky-Allen, Olga Shvestova, and Andrei Zhirnov. Julie VanDusky-Allen is an assistant professor at Boise State University. Her research focuses on both formal and informal institutions, legislative organization, political parties, political participation, and support for and satisfaction with democracy. Olga Shvestova is Professor of Political Science and Economics at Binghamton University (SUNY). Professor Shvetsova's research focuses on determinants of political strategy in the political process. Broadly stated, these include political...

This is a guest post by Ryan Lloyd, a Visiting Assistant Professor of International Studies at Centre College. His research focuses on comparative political behavior and vote buying, particularly in Brazil. He can be reached at lloydr418@gmail.com, and on Twitter at @Lloyder2323. Public health and political crises The numbers were disastrous. After months of denialism, Brazil had just passed Italy into third place for official deaths related to COVID, and was hot on the UK’s tail, with 35,930--more than 1,000 were dying per day. And despite massive undercounting of cases, it was already in...